Black Lives Matter activist Shaun King is at the center of a firestorm over an article he wrote last weekend about sexual harassment allegations against Peyton Manning by a female trainer at the University of Tennessee when the quarterback went to school there in 1996.

King’s involvement in the story — which followed several other articles he wrote alleging that Carolina Panthers quarterback Cam Newton is the victim of a racial double-standard — has led to a bitter back-and-forth on social media, sports radio and sports television.

King’s article and the claims made against Manning, whose Denver Broncos defeated Newton’s Panthers in the Super Bowl, have been thoroughly discussed. Now the attention has turned to King himself, with some professional sports commentators pointing to reports about King’s own past that suggest that he should not be the one to throw stones at Manning.

Some of those accusations are that King, who identifies as black and says he has a white mother and black father, is white. Other King critics cite reports — including from The Daily Caller — that he has given inconsistent statements both about charities he’s operated and about an alleged hate crime attack he suffered in 1995 as a student at Woodford County High School in Versailles, Kentucky.

Fox Sports commentator Jason Whitlock, who is black, has been among King’s most vocal opponents. He has alleged that King is white and also pointed to reports questioning his charity work.

The criticism prompted a sharp response from King, who accused Whitlock of being a “coon” and a “Uncle Tom” and of selling out to the white establishment media.

It makes sense that @WhitlockJason was fired (twice) by ESPN and now works for Fox. You fit right in there man.

Dude will coon for cash.

— Shaun King (@ShaunKing) February 17, 2016

TheDC has reported extensively on these topics and can now provide new information. Some of it is supportive of King’s past claims. Some is not.

Is Shaun King black? Was he the victim of an anti-black hate crime?

TheDC first reported in July that King’s claims — made in interviews, online, and in a self-help book he wrote — that he was the victim of a hate crime attack by up to a dozen white racist rednecks while a high school student in Versailles, Kentucky on March 1, 1995 was not consistent with a police report written at the time of the incident. TheDC also talked to the police detective who worked the case, Keith Broughton, who said that he saw no evidence that the attack was racially motivated. (RELATED: Leading Ferguson Activist’s Hate Crime Claims Not Backed Up By Police Report, Detective)

The next month, Breitbart News published King’s birth certificate. The document listed both King’s mother and father as white. The report prompted comparisons of King to Rachel Dolezal, the former president of the Spokane NAACP chapter who lied about being black.

King responded, asserting that his mom had had an affair with a black man and that he had avoided discussing his complicated racial background out of respect for her and the rest of his family. He also stood by his claim that he was the victim of a hate crime in high school.

To follow up on its initial report, TheDC requested and obtained legal documents from a lawsuit King and his mother filed after he was beaten up in high school. The suit alleged that school administrators did not do enough to protect King from the attack. The case was eventually dismissed.

The court documents answer several questions, while raising others.

First, they do support King’s claim that he underwent several back surgeries as a result of the attack. The police report compiled after the incident listed King’s injuries as minor. Broughton, the Versailles detective, told TheDC that if King suffered internal injuries he would not have had a way to know. He was not contacted with any follow-up about King’s injuries, he said.

King is also vindicated by a deposition given by the student who attacked him in 1995. The student, who was expelled from school and faced assault charges, said that he sucker-punched King between school periods because his girlfriend had told him that King choked her and threatened her over a broken CD.

The girl had submitted a statement claiming that King had threatened her.

In the deposition, the attacker said that he later found out that his girlfriend had likely lied to him about King threatening her. He said that he found out later the the girl was a compulsive liar. He also said he regretted attacking King over it and had learned not to take another person’s accusations as fact.

But the student also claimed that he believed that King was white and that race had nothing to do with his attack against his schoolmate.

The documents do not provide a clear answer to the question of how many people were involved in beating King. King has said that numerous classmates — up to a dozen — took part in the melee. In his March 21, 1997 deposition, King said that he could not say for sure how many people were involved in the attack. He said only that he believed several people were involved because he was receiving blows on different parts of his body simultaneously.

Some witnesses to the incident — including a teacher — said that they only saw only two people involved in the fight, King and his attacker. Others said that they saw multiple attackers beating King. The attacker himself said that he did not remember if others were involved.

King’s racial background is muddled by other documents contained in the case file, including from King’s mother.

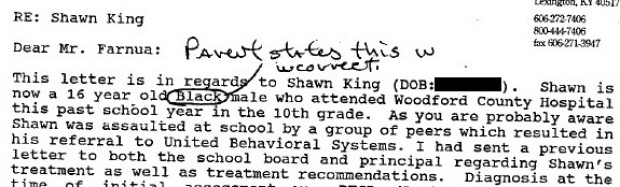

A report from a school counselor written on July 26, 1995 shows that King’s mother corrected the characterization that King is black.

“Parent states this is incorrect,” reads a notation referring to a description of King as black.

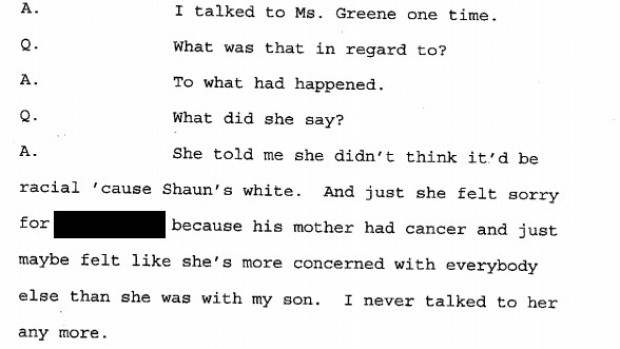

King’s mother also indicated during her deposition that her son was not black. She also said that a vice principal at the school — a black woman named Drexel Greene — told her that King could not have been the victim of a hate crime because he was white.

Passage from Kay King’s deposition, March 21, 1997.

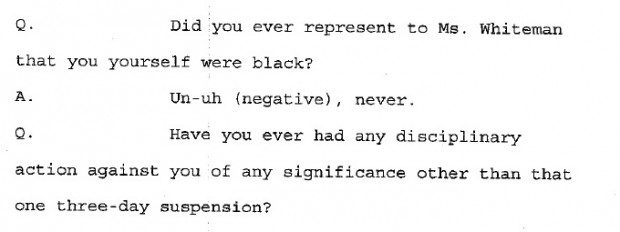

King’s own deposition raises questions as well. In it, King was asked if he had ever represented himself as black to an English teacher.

“Un-uh, never,” King responded.

Passage from Shaun King’s March 21, 1997 deposition.

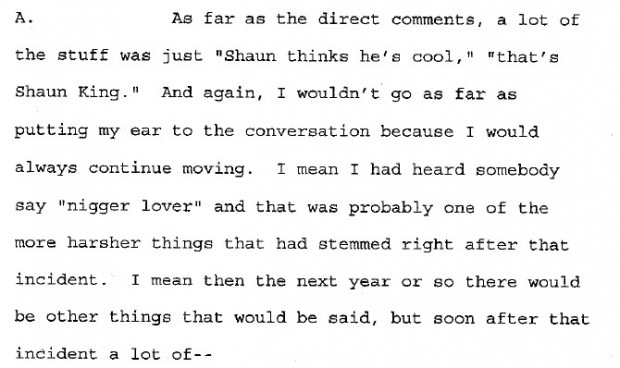

King did say that other students had made racially insensitive remarks to him. But those comments indicated that the students were lashing at out King because his friends were black.

King said that a group of students had called him a “nigger lover” months before his attack.

Passage from Shaun King’s March 21, 1997 deposition.

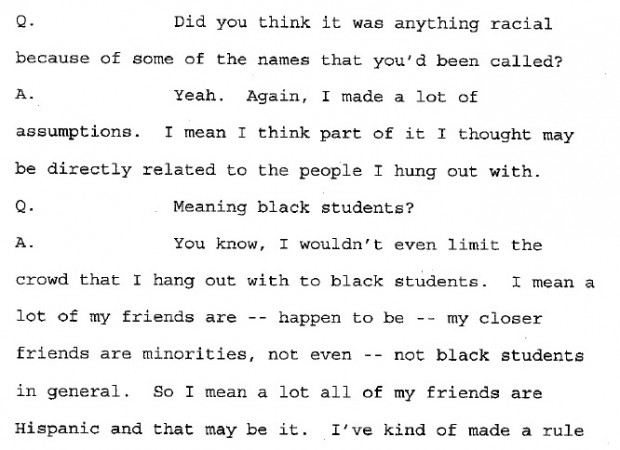

King said he did believe that the attack against him may have been racially motivated, but mostly because of the people he hung out with. He said that many of the students present during the fight were agriculture students who he said often wore Confederate flag attire. Much of the depositions in the court papers discuss racial tension at Woodford County High School during that time period.

Passage from Shaun King’s March 21, 1997 deposition.

In his bitter back-and-forth with Fox Sports’ Whitlock, King stated that he “everybody” in his hometown knew that he was bi-racial. Ironically, he cited Versailles Det. Broughton’s comments that he believed during his investigation that King was bi-racial. Broughton told news outlets, including TheDC, that he checked the “white” race category on the police report because there was not a box for bi-racial. Ironically, King chose to cite Broughton’s statement about his being bi-racial but disputes the detective’s assessment that the 1995 attack was racially-motivated.

Where the police officer says in 1995 EVERYBODY in our whole damn town knew I was bi-racial, including him. pic.twitter.com/fJhMjeWfgg

— Shaun King (@ShaunKing) February 17, 2016

NEXT PAGE: King’s Charities Less Than Transparent

King Con? Charities are less than transparent

Hours after TheDC reported in November on several inconsistencies in King’s statements about charities he’s operated over the years, the writer announced that he was returning donations given to two of them, Justice That’s All and Justice Together. (RELATED: Charities Founded By Shaun King Appear To Never Have Existed)

TheDC reported — based in part on complaints made by members of the Black Lives Matter movement — that King had failed to follow through on a promise to use funds from Justice That’s All, which he founded in August 2014 just after the police shooting death of Michael Brown, to file as a tax-exempt organization.

But after volunteers plugged away on the project for several months, King shut down the operation without notice. He also ignored refund requests from donors and demands to provide an accounting of expenses. He also never registered Justice That’s All with the IRS or as an incorporated charity with any state.

Months later, King announced the creation of Justice Together, a social justice non-profit that closely resembled Justice That’s All. But this operation appeared better primed for success. Besides having King’s increased profile as an asset, Justice Together brought Black Lives Matter leader DeRay Mckesson on board. Journalist Glenn Greenwald also joined the board of directors.

But as with Justice That’s All, Justice Together went south too. Donors and volunteers began to complain after King failed to provide updates about the organization. He announced he would shutter the group. And after TheDC reported on the donors’ complaints and inconsistencies in King’s comments about his charity work, he announced he would return the donations given to both Justice That’s All and Justice Together.

While King apologized for failing his donors and volunteers, he continued to obfuscate the nature of the two organizations. He claimed that Justice That’s All was an offshoot of Justice Together. But King’s incorporation documents for Justice Together show that he created it in July 2015, well after Justice That’s All had ceased operations.

And though King portrayed his returning donations as a courtesy, the fact remains that he did so only after TheDC’s report and after being hounded by his fellow Black Lives Matter activists.

Following a report by The Daily Beast asking how King allocated donations from the charities, King published an essay that he claimed provided a full accounting of his charity work, including receipts. But the report was limited and provided no receipts for Justice Together or Justice That’s All.

It also did not provide an accounting of money he raised for a group he founded in 2010 called A Home in Haiti. That organization began raising funds in February 2010, a month after the massive earthquake in Haiti. King registered the group with the IRS in August of that year. The next year, King changed the name of the organization to Homemob and refashioned it as a fundraising website for those in need.

King has provided little transparency for A Home in Haiti/Hopemob. A form 990 was filed with the IRS in 2013. It shows that Hopemob raised $420,000 that year in grants and contributions. King was paid a substantial ratio of those funds — $160,000 in salary and benefits. That’s compared to only $198,000 that was paid out in grants.

This week, TheDC learned from the IRS that A Home in Haiti/Hopemob did not file 990s for 2010, 2012 or 2014. That despite having raised as much as $2 million in 2010, according to some public statements. The entity did file what’s known as a 990-N in 2011. That form is used for non-profits that receive less than $50,000 in contributions.

TheDC caught King in another charity inconsistency. In April 2013 he claimed in several interviews that a social media company he had co-founded called Upfront Media would be sending a portion of its revenues to an affiliated foundation that had been created called Upfront Foundation.

“It’s very much a social engagement platform in that sense, but a percentage of every transaction that we have, which we’re really proud of, will go to a new foundation that we’ve started called the Upfront Foundation,” King told the Christian Post in April 2013.

Except that entity was never created. Upfront Media’s CEO, Ray Lee, told TheDC by phone that it was never started. By way of an explanation, King asserted that the company did not take off as planned and that there was no money to contribute to the foundation. King sold his stake in the company for a reported $200,000. But he has not explained why, in 2013, he referred to the Upfront Foundation as if it had already been established.