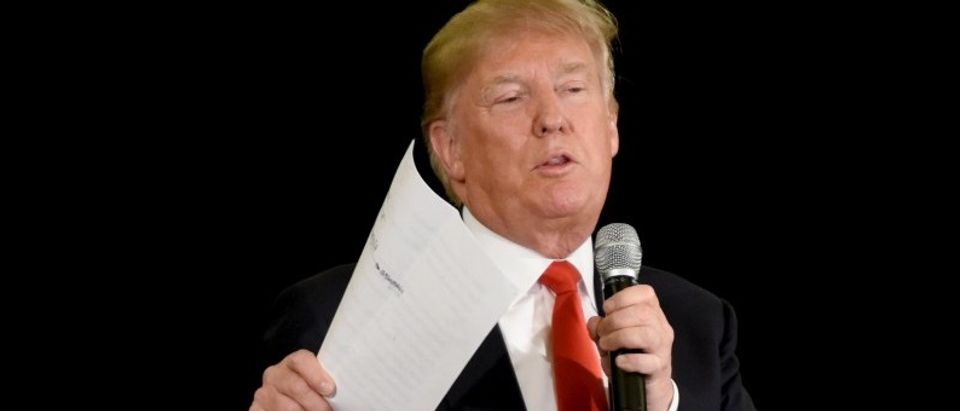

At the Republican debate on March 10 Donald Trump opined, “I think that whoever gets the most delegates should win,” rejecting current GOP rules that require he amass 1,237 delegates to secure the party’s nomination.

Not since the 1972 Democratic convention has there been so much talk about delegates – those authorized to represent voters at a political party convention – in a presidential election cycle. Similar to the Electoral College, the concept of using delegates at all is arguably unrepresentative of We, The People.

In today’s technologically interconnected America, where information is more accessible and plentiful than ever before, voters relying upon party standard bearers to elect nominees is out of date. Used by the Republican and Democratic parties to narrow their respective field of presidential contenders, delegates are more reflective of party systems dominated by technical rules and party elites, than truly democratic processes.

In response to Trump’s comment, Republican strategist Karl Rove chronicled how, since 1860, GOP delegate rules propelled five of its candidates – Lincoln, Hayes, Grant, Harrison, and Harding – from obscurity to the White House. Rove asserts, essentially, that because unpopular candidates-turned-President leveraged delegates to win the GOP nomination, such rules are inherently fair, and should be maintained.

While one can appreciate Mr. Rove’s respect for tradition and history, we should not be beholden to either. Trump makes a valid point: The person who gets the most votes should be a party’s nominee. Plain and simple.

The Democratic Party is no better. Its rules, which have gone through several iterations since 1968, proportionally allocate pledged delegates to candidates in the primaries and caucuses – perhaps a more just approach than the GOP’s winner-take-all method. But while the Constitution guarantees every citizen the right to one vote in the general election, the Democrats guarantee party bigwigs and influencers the right to two during the nominating process – once as a primary voter, and again at the convention.

Superdelegates – elected officials and other party insiders allowed to support at the convention whichever candidate they wish – make up about 15 percent of the Democratic Party’s delegate count. They are unpledged to any particular candidate, and therefore can overrule the will of voters. (While most Democratic primary voters in 2008 supported Hillary Clinton, superdelegates favored Barak Obama, resulting in him clinching the party’s nomination.)

Democratic Party chairperson Debbie Wasserman Schultz described the need for superdelegates, saying, “Unpledged delegates exist, really, to make sure that party leaders and elected officials don’t have to be in a position where they are running against grassroots activists.

The Democratic Party’s delegate system is, clearly, unashamedly undemocratic.

In February, Rep. Alan Grayson (D-FL) announced he would allow Internet users to decide his superdelegate vote. “I’d be perfectly happy if our nominee were chosen exclusively in the primaries,” Grayson said. “But 15 percent of the delegates to the Democratic Convention are chosen because of who they are, not whom they support. And I happen to be one of them. I wrestled with that responsibility for a while, until I realized that I don’t have to decide – I can let you decide.”

Grayson’s commitment is not only an almost unheard of move in American politics; it represents the possibilities of the future – technologically, and in terms of sentiment towards primary voting and delegate systems.

But there is a flip side to all this anti-delegate rhetoric. Some believe delegates provide a necessary check on populist emotion. The general public, so goes the thinking, does not rightly know what makes a good candidate. Unpledged delegates therefore create a balancing effect that may cool the passions of the masses.

For example, the GOP establishment feels that the lunatics have taken over the asylum, as Republican primary voters have mostly favored The Donald over all other GOP options. Viewing Trump as unpalatable, the establishment is trying its best to prevent him from clinching the party nomination. Trump validates the GOP’s justification for using unpledged delegates: If an acceptable candidate is not selected via primary voting and Trump does not amass the required number needed, unpledged delegates can act as a safety valve and create a ‘way out’ for the party elite to essentially oust Trump from the convention in July.

President George Washington famously warned against the two-party system in his 1796 Farewell Address: “There is an opinion that parties in free countries are useful… This within certain limits is probably true… But in those of the popular character, in Governments purely elective [like the U.S.], it is a spirit not to be encouraged.”

One can only imagine what our first president, if he were alive today, would have to say about parties outsourcing the peoples’ wishes to delegates.

Armand V. Cucciniello III is a public relations and communications executive, writer, and commentator. He is a former U.S. diplomat, and has served as an advisor to the U.S. military in Iraq and Pakistan. He has written for Dow Jones Newswires, TIME, USA Today, and has appeared on many TV and radio programs including NPR and CNN. Cucciniello received his B.A. from Boston University and an M.A. from Syracuse University. He has studied, worked, lived, and traveled throughout the Middle East and South Asia. Follow him on Twitter @ArmandVC3.