A study conducted by a Harvard labor economist disproves a widely-cited study that argued that the influx of workers in Miami from the Mariel Boatlift did not adversely affect the wages of native Miamians.

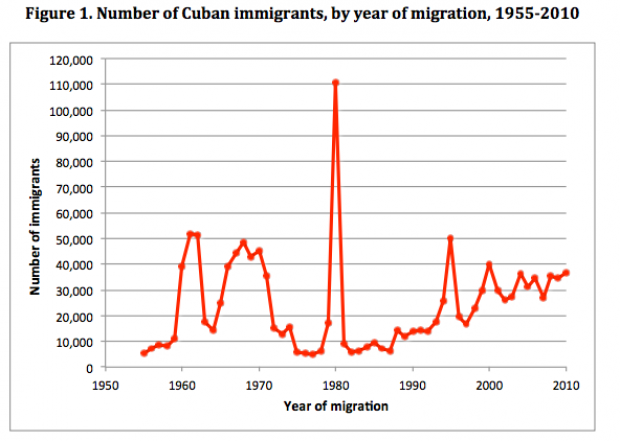

The Mariel Boatlift brought over a hundred thousand Cubans to the United States over the course of a few months in 1980. A study from David Card in 1990, which has been cited 1452 times according to Google Scholar, looked at wages in Miami before and after the boatlift.

“This study shows that the influx of Mariel immigrants had virtually no effect on the wage rates of less-skilled non-Cuban workers,” Card concluded. A peer-reviewed paper written by Harvard professor George Borjas set to be published in the Industrial and Labor Relations Review, the same journal Card was published in, finds many issues with the 1990 study.

“The Mariel supply shock was composed of disproportionately low-skill workers; about 60 percent were high school dropouts. Remarkably, none of the previous examinations of the Mariel experience documented what happened to the pre-existing high school dropouts in Miami, a group that composed over a quarter of the city’s workforce,” Borjas writes. Borjas, himself a Cuban, is a labor economist at the Harvard Kennedy School who is a known proponent of reducing immigration rates.

“Mariel increased the size of the labor force by 55,700 persons, of which almost 60 percent were high school dropouts. Although the Mariel supply shock increased Miami’s workforce by 8.4 percent and increased the number of the most educated workers by 3 to 5 percent, the number of low-skill workers rose by a remarkable 18.4 percent. Moreover, this supply shock occurred almost overnight. The Coast Guard reports that the first Marielitos arrived in Florida on April 23, 1980, and that over 100,000 refugees had been admitted by June 3,” Borjas writes.

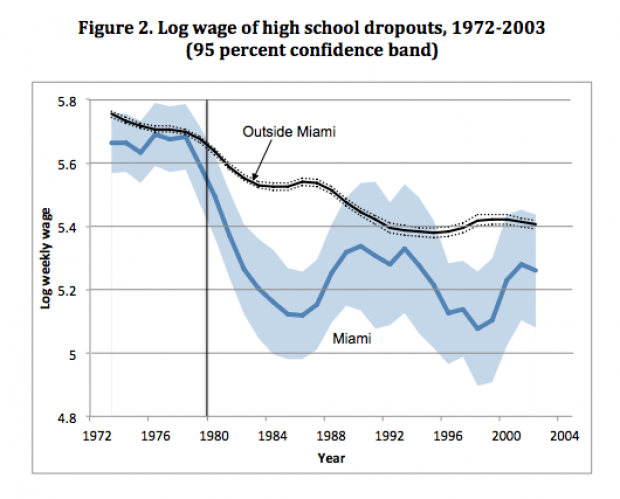

“Although it has been claimed that perhaps high school dropouts and high school graduates are perfect substitutes and should be pooled to form the low skill workforce, the Mariel data clearly contradicts this conjecture.” The study found that better educated workers in Miami did not experience a substantial drop in wages the years following the Mariel Boatlift.

“The average wage of male high-school dropouts in Miami fell by about 37 percent between 1976-1979 and 1981-1986,” Borjas found. The labor economist described this as a “very unusual event.”

“The Mariel experience ranks in the first percentile of the distribution of all observed wage changes between 1976 and 2003 across all metropolitan areas.”

He also criticized the cities Card used to compare Miami to in his study. “It is important to emphasize that the four cities in the Card placebo were chosen partly based on employment trends observed after the Mariel supply shock. Put differently, if Mariel worsened employment conditions in Miami, the Card placebo is comparing the poorer outcomes of workers in Miami to the outcomes of workers in cities where some other factor worsened their opportunities as well.”

Borjas concludes that “something unique happened to the economic status of high school dropouts in Miami in the early 1980s.” The impact of the “Marielitos” on workers in Miami was “targeted very narrowly on workers who lacked a high school diploma.”