Work was a supporting pillar in my family dynamic growing up, instilling a foundation that would ultimately propel me to achieve all of my career and financial goals I had set for my 25 year benchmark. Those goals are personal and private, but I am ecstatic that with just about five months to spare, I’ve exceeded them all.

That foundation was built by years of watching and learning from my father, Joseph Merse, who has taught – and continues to teach me – what it means to work hard and provide for a family.

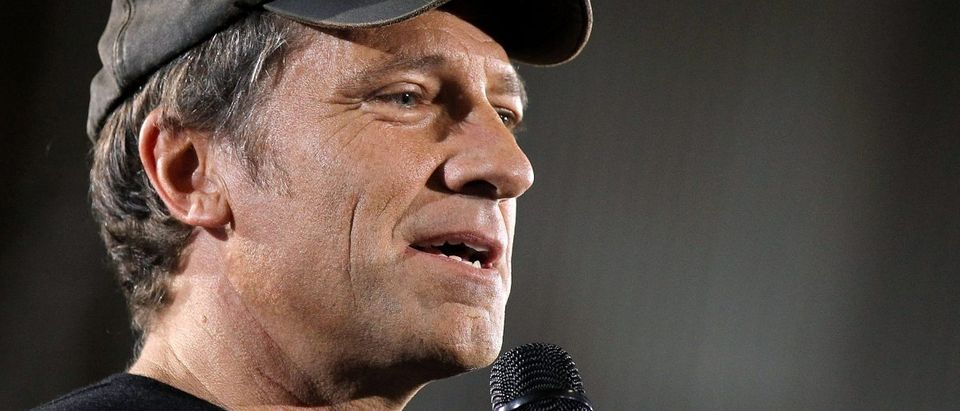

Americans like my father that take pride in their work propelled Mike Rowe to become “the dirtiest man on TV” with his notorious show Dirty Jobs and one of the leading American men tackling the issues related to the widening skills gap through his foundation, mikeroweWORKS Foundation, which awards scholarships to students pursuing a career in the skilled trades.

Rowe has been a role model for me, my father and countless friends of mine that have all reached career and financial stability and success by employing a simple concept – working hard for everything we have.

Fortunately for younger generations that may not have grown up watching “Dirty Jobs,” the show is syndicated, and though Rowe couldn’t tell me many details, it’s very likely that the CNN spinoff “Somebody’s Gotta Do It” may soon follow suit.

I asked Rowe for his thoughts on the impact the working man (or woman) has on American lifestyles – considering he worked more than 300 different jobs in all 50 states.

“My working theory for Dirty Jobs was that anonymous people in towns you can’t find on maps are doing the jobs that make civilized life for the rest of us possible,” Rowe said. “I’m still doing the same thing today, in a slightly different way, but my foundation can be reduced to an individual doing a job that is far more important than society realizes.”

That slightly different way is his new show, “Returning The Favor” on Facebook, which has received more than 54.5 million views of the seven currently released episodes. In this series, Rowe travels the country in search of remarkable people making a difference in their communities.

For as long as I can remember my father would pull up his Red Wing work boots and be out the door by 4:30am to get to Kearny, NJ and begin work by 6 or 7 o’clock, always working for Linde-Griffith Construction as a union dock builder turned Local 15 operating engineer. My father left in his blues, and came home pretty much black, covered in grease and oil and dirt.

To this day I love the smell of diesel fuel, it smells like my father, it smells like love and it smells like success.

A few times a week we can all catch a whiff of the stink of the neighborhood’s trash as it sits on the curb waiting for pickup. Some people are grossed-out by that, and couldn’t fathom hauling it away and dealing with the smell, but I see those small piles of trash as small mountains of money for someone to provide for their family.

From a young age I thought getting up and going to work was cool – I saw my dad do it daily, eventually learned about his paychecks and connected the dots between him pulling up those boots to that little piece of paper to the food I ate every night at 5pm for family dinner.

My dad is tradesman and has been all of his life. He welds, he is licensed to operate heavy equipment like Manitowoc 4000W crawler cranes, and carries a universal Caterpillar key on his key ring.

He’s fixed heavy machinery with names I can’t event pronounce, and he made sure my sister and I both can change our own oil, brakes and change and fix flat tires. He knows basic electricity and plumbing skills and I’ve never seen a tool he doesn’t know how to use.

I mentioned this in my 9/11 story, but it’s worth reminding my readers that my father’s skillset was vital after the towers fell in lower Manhattan. As an operating engineer, he holds the necessary credentials and licenses that were needed to operate the machines used to clean up the wreckage.

Another example of my father’s skillset being able to help others involves an infamous generator that’s big enough to power the entire neighborhood if properly hooked up. During the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, much of New Jersey was without power, but my father had our entire house lit up and fully functional – a sanctuary for family, friends and neighbors that needed a hot shower, to cook perishables or just hang out for a while.

My father’s conventional wisdom is cool, and it’s not something I see often in corporate America or academia.

Learning Is Not Limited To The Classroom

Rowe was on Fox News discussing “making work cool again” and that resonated with me. Many of my peers look at me, my properties and my lifestyle and tell me I got lucky. But luck had nothing to do with how I got to where I am now.

They think it’s cool that I am successful now, but they didn’t think I was cool when I was working multiple jobs through high school, college and post-grad to achieve all of my goals. Nobody thought it was cool to be tired at 9pm on a Friday night.

When I was 13 or 14, I pulled staples for a family friend that owns an upholstery shop in my hometown. At 15 I started working as a lifeguard, and picked up another job at the local carwash. By 19 I was also scrubbing toilets as a janitor at the community club house. At some point I even served burnt coffee at a coffee house.

When I’m at my day job or here at my desk writing, I know that I am making my father proud, and I know that I have earned his respect as a working man and provider. I can even pull up the same Red Wing boots hold my own with him for the occasional side job he asks me to help with, or to rake the leaves or mow the lawn.

They were big shoes to fill, but they finally fit.

It’s cool that I can change my own light switches, install a new sink and vanity and once I even tiled my own bathroom floor.

It’s cool that I am a completely independent man at the age of 25.

It’s cool that a woman at my day job in a corporate office asked me to stop by one day and help her hang family photographs – I made a new friend and I can’t wait to help her.

None of my jobs growing up were particularly glamorous, but I learned valuable skills at all of them. While discussing the various things I’ve done in my life, Rowe reminded me that even though I have a white-collar day job, I still carry these skills in a toolbox with me every day.

I believe any honest work is good work, and Rowe noted that there are 6.2 million jobs available right now and 75 percent of those do not require a four-year college degree, but our cookie cutter approach which shepherds high school students en masse to four-year universities really doesn’t help students see the trades as a viable alternative.

“For a long time, the skills gap simply wasn’t [even] written about. 15-20 million people were unemployed at the height of the recession at the same time as millions of jobs going unfilled,” Rowe said. “No one was writing about the existence of opportunity, but everyone was writing about the lack of opportunity.”

One of the most alarming things Rowe pointed out was that we currently still push a four-year degree as the best path forward for the largest numbers of students, while slowly killing shop class in American high schools.

“When you start calling vocational arts ‘shop,’ it’s pretty easy to take shop class out back and put a bullet in its head,” Rowe said. “That’s what we did; we killed shop class, which sends an undeniable message to millions of kids in terms of what is valuable.”

Now that we have a presidential administration that values the American work force – like the coal miners in Allegheny County and the men and women that build Boeing 787s South Carolina – an opportunity to change the narrative is within reach.

If parents and guidance counselors team up to reinstate the vocational arts programs, enhance the work-study options and celebrate the trades again, the opportunities are limitless for the next generation.

We’ve got work to do, and we can’t be afraid to get dirty.

WV COAL MINERS BELIEVE TRUMP WILL BRING COAL, MANUFACTURING BACK TO US:

James Merse is a healthcare communications professional from Northern New Jersey and teaches communication courses at community colleges. Follow him on Twitter: @JamesMerse

Views expressed in op-eds are not the views of The Daily Caller.