When Billy Graham delivered his final crusade in 2005, I was still a young teenager. As a member of a generation which lightly esteems anything before the internet, it seems unlikely that I would mourn the death of an old country preacher who became famous proclaiming a Savior from 2,000 years ago. Like many of my cynical peers, I bristle at much of what passes for evangelicalism today. But the plainspoken, old-time religion of the Rev. Graham cuts through millennial snark like nothing else, and has reached across the generations to my life through curious, inescapable ways.

My father grew up in Altoona, a spiritually dark railroad town in central Pennsylvania. Once a hub of industry, it has since fallen off the map. It was last seen in the headlines when it was exposed as one of the nation’s most egregious underbellies of clerical sex abuse. Three months before the 1949 Los Angeles Crusade that would draw the attention of William Randolph Hearst and catapult him to fame, the 30-year-old Billy Graham held a revival in Altoona. It proved to be his temptation in the wilderness.

Graham’s associate, Grady B. Wilson, called it “the sorriest crusade we ever had.” The local ministers bickered among themselves and offered measly support. Graham’s preaching was interrupted by a large insane woman who stormed the stage, threatening to kill the music director and screaming that Indians were trying to kill Billy himself. It took three grown men to restrain her. According to his autobiography, Graham left Altoona “discouraged and with painful cinders in [his] eyes.” He was convinced that “Satan was on the attack,” and pondered “whether God had really called [him] to evangelism after all.”

Billy Graham, the American evangelist, preaches May 20, 1957 at Madison Square Garden in New York. (AFP/AFP/Getty Images)

It will always give me pause that, decades later, my father became a Christian because of Billy’s preaching. First was the inexplicable appearance of a Billy Graham tract in his parents’ home. A week later, he watched one of Graham’s televised sermons. For a young man spiritually suffering and searching, Billy’s straightforward exegesis was enough to convert him. At length he would attend seminary and deepen his understanding, but it was the simplicity of the gospel that snatched him like a coal from the spiritual furnace of that dying Rust Belt town.

Some perennial critics fuss that Graham did not adequately delineate the finer points of theology by which Christians are divided. But he was both a gracious diplomat, and a shrewd rhetorician. He sought to cast the net of his message as broadly as he could, and by his mastery of television did so more effectually than anyone before him.

Over 30 years after my father’s conversion, my parents settled in Asheville, North Carolina, where Graham’s influence is palpable. The freeway leading into the city is named for him, and he spent his final years in Montreat — a quiet mountain town about 18 miles away, where I have spent much time.

Growing up in that small community, I often encountered his unassuming friends and family. I went to school with his great-grandchildren, cleaned his daughter’s gutters and even ran into his musical associate, George Beverly Shea, at a local restaurant while he ate a piece of birthday cake. When hiking with friends, we would point out Billy’s house as we saw it from an overlook, nestled in the blue folds of the mountain. It was strange to think that down in that modest cabin lived a man who had preached in person to nearly 215 million people, more than anyone in history.

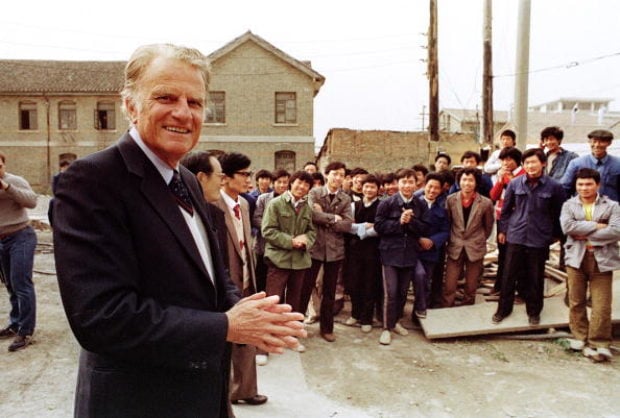

Billy Graham, the American evangelist, addresses Chinese faithful on April 20, 1988 in front of his wife Ruth’s birthplace in Huaiyin, Jiangsu province, China. (JOHN GIANNINI/AFP/Getty Images)

In 2013, I witnessed myself the range of his impact during his 95th birthday party at the Asheville hotel where I was working as a busboy. I saw Graham’s shock of white hair from a distance as I went about my menial work (trying desperately to keep from dropping my enormous tray while the 1,000-person banquet streamed live on television).

Luminaries of wealth and influence mingled with people whom I saw regularly in my unremarkable life. As Donald Trump swept past me in the hall on his way out, the dinner struck me as an apt metaphor for Graham’s life and message. The gospel carried by a North Carolina farm boy into the halls of power transcends this world, and asserts that Christ alone is the only hope for busboys and presidents alike.

Against the idols of the age, Graham stood firmly. He prayed with presidents, but lacked faith in the ability of government to usher in the Kingdom of Heaven. He believed the source of evil was not external institutions, but the human heart. He remained convinced that the greatest doom facing the human race was not economic inequality or global warming, but alienation from God.

For such reasons, he was seen as a heretic by some, and will continue to be. His message of the Cross is foolishness to an era convinced of its own progressive enlightenment. Were his ministry to begin today, the inconvenient moral implications of his basic Christian teaching would leave many gnashing their teeth at him, likely chasing him from the public square altogether. The world has grown cynical toward televangelists, and not without reason: Few could meet the standard set by Billy Graham. It may be that the world will never see the likes of him again. He was a man uniquely gifted for a new medium at a unique moment in history.

Members of the public view Christian evangelist and Southern Baptist minister Billy Graham’s casket as he lies in honor in the U.S. Capitol Rotunda Feb. 28, 2018 in Washington, D.C. (Chip Somodevilla/Getty Images)

That his funeral competes for news coverage with another mass shooting is a poignant testament to the human toll of a culture that has largely rejected Graham’s message. As the social influence of Christianity recedes from the Western world, the long-term fruit of the seeds he sowed across the latter half of the 20th century will become increasingly precious.

I had hoped one day to meet him, and to thank him for the preaching which had influenced my father, and by extension me. But alas, he always remained a single degree of separation away. Like myriad others, his influence upon me was not direct, but an echo. If that gospel he preached is true, it is an echo that will resound forever.

Rest in peace.

The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of The Daily Caller.