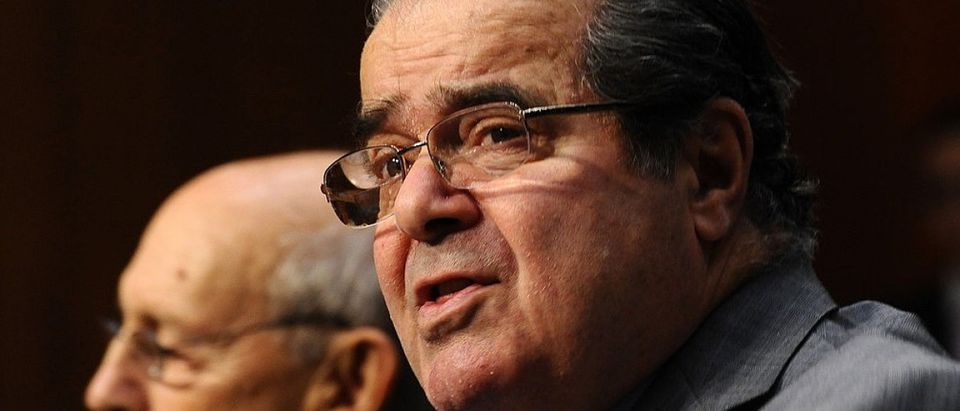

Conservatives are hunkering down after Justice Antonin Scalia’s death, determined to prevent President Obama from naming a liberal replacement. That’s understandable: Scalia was an eloquent and effective voice for conservatism, and key to the often single-vote majorities that conservatives have mustered on crucial issues for many years now. Were he replaced by a more liberal justice, the divisions on the Court would become even thinner, with each side increasingly polarized about the meaning of our Constitution.

But some of these fears are exaggerated. Scalia was not always a friend to conservative beliefs, after all. His rulings were often inconsistent, and he admitted it, calling himself a “Faint-hearted Originalist.” In one tough case involving the constitutionality of the nation’s 45-year long War on Drugs, for example, Scalia chose not to embrace the views of America’s founding fathers, but wrote an opinion that upheld federal power far beyond what they envisioned.

In another case, he explicitly refused to follow the original meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment, which protects the “privileges or immunities” of citizens. Rather than enforcing the original meaning of that provision, he relied instead on a legal theory known as “substantive due process,” which protects individual rights to a more limited degree — even though he’d spent decades denouncing that theory. He even mocked a lawyer who argued that this was not what the Amendment’s authors intended: “you’re bucking for a place on some law school faculty,” he said.

Conservatives were often frustrated with Scalia’s rulings. In 1990 he established a legal test for determining when laws excessively intrude on people’s religious beliefs. Where previous rulings had required the government to back away from unduly limiting religious practices, Scalia held that the Constitution does not “bar application of a neutral, generally applicable law to religiously motivated action.” In other words, if a person’s religious beliefs conflict with a law, too bad. Religious conservatives have struggled ever since to reverse that decision. Conservatives were likewise disappointed in a case called City of Arlington v. FCC, when Scalia — usually skeptical of the powers of unelected administrative agencies — wrote an opinion that requires judges to accept these agencies’ rulings regarding the scope of their own powers. Even the moderate Chief Justice John Roberts dissented in that one. He, along with Justices Samuel Alito and Anthony Kennedy, thought agencies needed stronger checks and balances.

Those who believe in constitutional protections for individual freedom often found Scalia an opponent, not an ally. He ridiculed what he called the “Thoreauvian ‘you-may-do-what-you-like-so-long-as-it-does-not–injure-someone-else’ beau ideal,” and went out of his way to distance himself from the principles articulated in the Declaration of Independence, when Justice Clarence Thomas cited them in two opinions in the 2000s.

On questions of free speech, freedom of religion, and criminal justice protections, Justice Scalia was often less than vigilant. He frequently ruled in favor of government’s power to post religious statements in government buildings or to issue official prayers on the taxpayer’s dime. He routinely ruled that government could censor speech it called indecent. And in Lawrence v. Texas, he wrote an impassioned dissent, arguing that states should be allowed to send armed officers into people’s bedrooms to arrest them for private, consensual sex whenever voters disapproved. States, he said, could even punish people for masturbating.

These opinions reflected Justice Scalia’s deep commitment to the idea that the majority’s will should almost always trump individual rights — the exact opposite of the view of James Madison, Father of the Constitution, who thought people are fundamentally free, and government restraint is the exception.

Any successor President Obama names is likely to have strongly left-leaning views — willing to uphold expansive federal power and limit the rights of property owners and entrepreneurs. But such judges are also likely to be more protective of people accused of crimes, or who don’t profess a traditional religion, or who think their private lives are none of the government’s business. And on some subjects close to the hearts of conservatives — federal power over personal behavior, or the exercise of religion — even a liberal successor might make little difference.

Justice Scalia was a brilliant and likeable man, an outstanding writer, and a judge who sincerely did what he thought best. But, as with his liberal colleagues, his record had its upsides and its downsides — and his successor will also have strengths and weaknesses. Conservatives may mourn his passing, but they should not panic about his replacement.

Timothy Sandefur is Vice President for Litigation at the Goldwater Institute and coauthor of Cornerstone of Liberty: Property Rights in 21st Century America (Cato Institute, 2016).