On Tuesday, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit will hear arguments in the litigation over President Barack Obama’s Clean Power Plan (CPP). If implemented, the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) regulation will require states to develop and bring into force plans to reduce carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from existing power plants.

The focus for opponents of the CPP will be its questionable legality. However, the ten judges hearing the case should also keep in mind that the rules are pointless. The CPP will have no measurable impact on climate.

EPA Administrator Gina McCarthy has repeatedly admitted exactly that before Congressional hearings. She asserts that the CPP is still worthwhile because, to quote from her September 18, 2013 testimony before the House Subcommittee on Energy and Power, it “is part of an overall strategy that is positioning the U.S. for leadership in an international discussion, because climate change requires a global effort.”

Setting a good example would make sense if it were known that a man-made climate crisis was imminent and developing nations, the source of most of the world’s emissions, were likely to follow our lead.

But developing countries have indicated that they have no intention of following the U.S. They will not limit their development for ‘climate protection’ purposes.

For example, on July 18, President Rodrigo Duterte of the Philippines said about the Paris climate agreement, “You are trying to stymie [our growth] with an agreement… That’s stupid. I will not honor that.”

Duterte can say this with a clear conscience. The UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (FCCC), the foundation of the Paris Agreement, gives an out clause for developing nations. Article 4 of the FCCC states, “Economic and social development and poverty eradication are the first and overriding priorities of the developing country Parties.”

Actions to significantly reduce CO2 emissions would entail dramatically cutting back on the use of coal, the source of 81% of China’s electricity, 71% of India’s, and 29% of that of the Philippines. As coal is by far the least expensive source of electric power in most parts of the world, reducing CO2 emissions by restricting coal use would unquestionably interfere with development priorities. So developing countries simply won’t do it. They will continue to grow their use of coal—the Philippines has a 7.2% annual increase in the rate of coal use for primary energy demand, for instance—citing the UN’s own treaty in support of their actions.

From a climate change perspective, it probably won’t matter in the least. After all, even the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change admits that surface temperature, averaged over the land and ocean, increased only about 1.5 degrees between 1880 to 2012 despite a reputed 37% rise in atmospheric CO2 content. And it is well known that the impact of further CO2 rise diminishes as the concentration increases.

Given that there has been no general increase in extreme weather or the rate of sea level rise, the primary rationale for the actions to restrict CO2 emissions is merely the possibility of dangerous climate change in the future.

Speaking on September 20 before the UN General Assembly, Obama summed up this concern, saying, “If we don’t act boldly [to restrict emissions], the bill that could come due will be mass migrations, and cities submerged and nations displaced, and food supplies decimated, and conflicts born of despair.”

But no one, not even the world’s leading climate experts, know this. The reports of the Nongovernmental International Panel on Climate Change (NIPCC) cite hundreds of references published in leading science journals that show that today’s climate is not unusual, and evidence for future climate calamity is weak.

Obama’s concerns are based on computer models of future climate states. But the models have failed miserably in the real world.

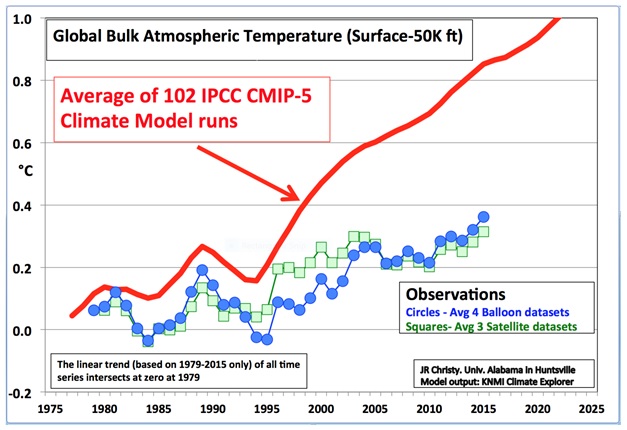

In his February 2, 2016 testimony before the U.S. House of Representatives Committee on Science, Space & Technology, Dr. John Christy, Distinguished Professor of Atmospheric Science, Alabama’s State Climatologist and Director of the Earth System Science Center at The University of Alabama in Huntsville, presented the following graph.

Five-year averaged values of annual mean global midtropospheric temperature as depicted by the average of 102 IPCC CMIP5 climate models (red), the average of 3 satellite datasets (green – UAH, RSS, NOAA) and 4 balloon datasets (blue, NOAA, UKMet, RICH, RAOBCORE).

Christy told Congress, “[T]hese models failed at the simple test of telling us ‘what’ has already happened, and thus would not be in a position to give us a confident answer to ‘what’ may happen in the future and ‘why.’ As such, they would be of highly questionable value in determining policy that should depend on a very confident understanding of how the climate system works.”

To create the models requires vast amounts of weather and climate data. We also need accurate data to input as the starting conditions for model-generated forecasts to be performed. Former University of Winnipeg professor and historical climatologist Dr. Tim Ball says that the collection and interpretation of the necessary data has only just begun. He explains that there are relatively few weather stations of adequate length or reliability on which to base model forecasts of future climate. “Obama’s worries therefore have absolutely no credibility in the real world,” Ball concludes.

After polling 9.7 million people from 194 countries, the UN’s My World global survey finds that “action taken on climate change” rates dead last out of the 16 suggested priorities for the agency. The judges hearing the CPP case on Tuesday must realize that, in comparison with access to reliable energy, better healthcare, government honesty, a good education, etc., most people across the world do not care about climate change. They understand that we have real problems to solve.