Feelings are running low in farm country – those states where Trump won in the election. In truth, feelings generally run low there – farmers never seem to have a ‘good’ year. Either the harvest is damaged and small, or booming and driving down prices. It’s latter right now. Further, farmers were looking forward to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) as the gateway to exporting more agricultural products and commodities. But TPP is dead. What will President Trump do?

In fairness, the farming community should have anticipated this when they voted for Trump, as he unambiguously denounced TPP. But they likely expected no joy from Hillary Clinton either, as she was going wobbly on TPP in the end stage of her campaign.

So TPP is kaput, President Trump wants to negotiate bilateral agreements, and the drafting of a 2018 farm bill (with trade provisions) looms on the horizon. No wonder farmers are nervous.

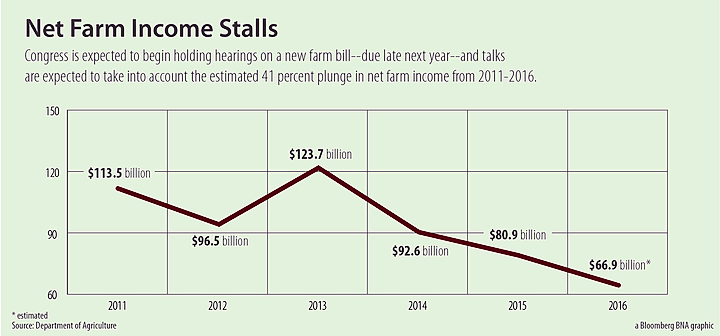

This Bloomberg graphic explains the U.S. ag situation at a glance:

In my opinion, President Trump should acknowledge that the U.S. team did a very good job in negotiating the ag sections of the TPP. The flipside is our team had a wide array of trade-offs, e.g., Japan lowering tariffs on U.S. beef in exchange for the U.S. lowering tariffs on something not agricultural. General practice is to keep trade-offs within a certain sector, but there’s no hard-and-fast rule about it.

Nevertheless, there is an urgent need for President Trump’s trade team to find a way to craft a ‘lifeboat’ to preserve U.S. successes via TPP in opening foreign ag markets.

Speeding the pace of bilateral agreements may be the answer.

Here’s why speed is important. TPP, if it had passed, may have gone into effect as soon as 2018. However, bilateral negotiations, if begun immediately and proceeding in a normal manner, might not conclude for at least two years, and would not take effect for six months to a year later. Thus, a bilateral agreement might not be fully realized until 2020.

And as hard as the President might push the U.S. team to conclude negotiations, his power to push the other side’s team is unknown. Plus, the President would not want to rush negotiations if it meant the U.S. team had to make hurried and harmful concessions.

A faster way to a bilateral agreement lies in following the 1980s U.S.-Canada Free-Trade Agreement’s example. Those negotiations involved a limited set of discussions; hot-button issues were postponed. The key part of the agreement was its allowance for further discussions on an annual basis. In fact, I was a negotiator for one of those subsequent rounds.

By limiting the initial bilateral discussions, while leaving the door open for further discussions at a later date (which, like the initial round, would involve Congressional oversight), it may be possible to speed up the pace of a bilateral agreement.

Plus, the ag agreements already reached in the TPP could be salvaged and reproduced in a limited bilateral agreement – the lifeboat.

The logic here is since country X already agreed to certain ag concession to the U.S. in the TPP, it can do so again in the bilateral agreement, with the U.S. reciprocating as it did in the TPP.

As the graph shows, the U.S. agricultural sector can’t wait for years for bilateral agreements to replace what they would have gained through the TPP. A slimmed-down bilateral agreement, using concessions already established in the TPP negotiations, may be the lifeboat our export-oriented ag sector desperately needs.