During the campaign, Donald Trump positioned himself as the non-interventionist candidate. His first few months in office have debunked this idea. Trump launched his first drone strike within days of his inauguration, and has intensified action on this front. In January, he also ordered a Special Forces raid in Yemen that killed civilians, as well as a Navy Seal.

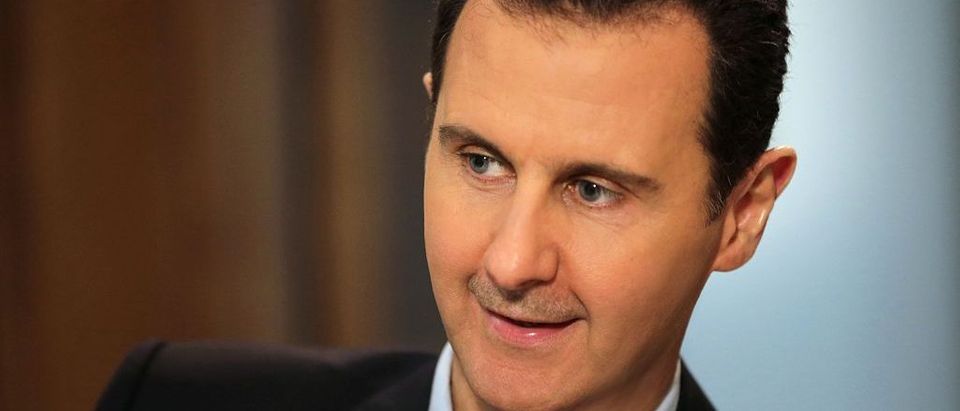

Now, he has officially entered the Syrian Civil War following a missile strike launched in response to the recent chemical attack on civilians. Senator Marco Rubio and others are now calling for regime change, and Secretary of State Tillerson says plans are being formulated to remove Syrian President Bashar Al–Assad. If the Iraq War and the intervention in Libya taught us anything, it’s that forceful ousting of a sitting government will fail, and therefore the US should resist doing so at all costs.

Anyone with a heart feels for the plight of Syrians trapped in what imaginatively is nothing less than hell. The images and videos emerging in the aftermath of the chemical attack are incredibly jarring. But the best policy is not for the US or other nations to further escalate the fighting. The long term consequences of intervention are impossible to know, and we risk creating a situation that will likely require a boots on the ground –– and leave Syrians worse off than before. The deposition of Libya’s Muammar Gaddafi left a power vacuum that was filled by people who were certainly disinterested in liberal democracy. Toppling Saddam Hussein sparked a civil war that has never ceased, prompting the US forces to re-enter the conflict in 2014.

There’s no guarantee that Syria would experience the same tumult as Iraq or Libya in the absence of Assad, but there is little reason to think that there is anything meaningful we can do to ensure that it doesn’t. The Federalist highlighted the questions that should be answered by politicians who wish to intervene to get rid of Assad. The most important question is number 14 on the list: “[w]hat lessons did you learn from America’s failure to achieve and maintain political victory following the removal of governments in Iraq and Libya, and how will you apply those lessons to a potential war in Syria?” Even if we’ve learned something from the events of Iraq and Libya, nation-building is incredibly tricky business and political victory in the form of a peaceful, functioning, even-somewhat-liberal democracy is unlikely.

In his book After War: The Political Economy of Exporting Democracy, economist Christopher Coyne looks at the US’s historical efforts at post-conflict reconstruction in other nations and finds the results less than stellar. Looking at efforts from various time periods, Coyne finds, at best, a 40 percent success rate and, at worst, a 28 percent success rate for enabling the creation of consolidated liberal democracies that do not rely on outside monetary or military support. Indeed, “the historical record shows more failures than successes and indicates that liberal democracy cannot be exported in a consistent manner at gunpoint,” writes Coyne.

Coyne contends that the incompatibility between formal institutions of government and the informal institutions and norms of society can contribute to failure. The formal government would need to be replaced with something that complemented the informal institutions, such as “the habits, knowledge, and beliefs necessary for the appropriate art of association” amongst varying groups of people. But these features are not ingredients one can look up in a cookbook, so attempting to plan for them would be an impossible task. Various factions in Iraq were unwilling to peacefully coexist with the imposed regime. Is there any reason to think Syria would be any different?

The United States should avoid getting further involved in this conflict. Even if President Trump were able to provide answers on all of the concerns involved, there is very little chance that anything we do will have a positive outcome in the long run. We shouldn’t sacrifice any more of our own blood and money for something that is doomed to fail. If President Trump’s heart is what guided him for the decision on the missile strike, then a better move would be to rethink his policy on Syrian refugees.

Jerrod A. Laber is a Program Manager at the Institute for Humane Studies. He is a Young Voices Advocate.