By Jon R. Sundra, Gun Digest

It was in 2002 that the Hornady folks set the rimfire world on its ear with the introduction of the .17 HMR (Hornady Magnum Rimfire), a cartridge based on the .22 WMR (Winchester Magnum Rimfire) case necked down to .17-caliber. Launching a diminutive 17-grain V-Max poly-tipped bullet at 2,550 fps, it opened a whole new world of possibilities for rimfire hunters and shooters. Actually, the development of a tipped jacketed bullet that wasn’t much bigger than a grain of rice was an achievement in and of itself, let alone launching it at centerfire-cartridge velocity.

To produce that kind of speed, the little bottlenecked cartridge operated at a MABP (Maximum Average Breech Pressure) of 26,000 psi, only 2,000 more than that generated by the .22 LR and the .22 WMR. With just an 8-percent increase in pressure, many existing bolt-action rimfire rifles proved stout enough to handle the cartridge. But semi-autos were a different story entirely. It wasn’t just the modest increase in operating pressure that posed the problem, but complicated dynamics with regard to bolt velocity and the low resistance of a super-light 17-grain bullet made the simple blowback action used in .22 rimfire semi-auto rifles unsuitable.

Savage was one of the first to solve the problem with its A17, a semi-auto designed expressly around the .17 HMR. However, it turned out to be more of a project than Savage envisioned. Though developing a totally new rifle was discussed as early as 2005, it would be seven more years before the company decided to go ahead with it, and another 2½ years to make it happen.

The key to solving the problem was to employ a delayed rather than a simple blowback action for the A17. Neither system has a bolt that “locks up,” per se, with the barrel or receiver; rather, the combined mass of the bolt and the spring(s) that power it provide enough resistance to delay the rearward movement of the bolt long enough for the bullet to exit the barrel and the pressure to drop before the bolt opens. Simply stated, with a delayed blowback, the system is designed so that the bolt has to overcome more resistance before it can begin its rearward movement.

In other words, the action stays closed a few milliseconds longer before the bolt can move rearward. This can be accomplished several ways, none of which are germane because the subject of this article is Savage’s newest addition to the A-series, the .22 LR Savage A22, which employs a simple blowback mechanism. About the only visible difference between the A17 and the Savage A22 in .22 LR is in the bolt handles, but internally the latter’s bolt and inner receiver are quite different.

The vital stats for the rifle sent to us for review had the gun weighing in at 5¼ pounds and measuring 41 inches in length with a 22-inch tapered barrel, which, interestingly enough, is threaded to the receiver and headspaced using a barrel lock nut, just like Savage’s centerfire rifles. That cannot but help the accuracy potential of this gun. Most inexpensive rimfire rifles sport non-tapered barrels that are press-fit to the receiver. A surprisingly stout and fully adjustable rear sight, and a towering front blade are standard. Also standard is the presence of pre-installed Weaver bases to greatly simplify the mounting of a scope.

The Savage A22 is fed courtesy of a 10-round rotary magazine that fits flush with the belly of the stock. The magazine is under mild spring pressure, so when the release latch is pulled, it pops out into your waiting hand regardless of the gun’s orientation — a nice feature. The straight comb on this classic-style stock is only ¾-inch below the bore line, and some shooters may find it difficult to cheek the stock low enough to use the iron sights. I was just barely able to use the irons, but then most shooters will opt for a scope. Length of pull is 13¾ inches, which makes it a full-size stock.

A 10-round, flush-fitting rotary magazine feeds the Savage A22. No malfunctions were experienced with the magazine during testing.

The barreled action is mated to its injection-molded polycarbonate stock by two Allen-head machine bolts; one is exposed forward of the magazine, but the rear bolt is accessed from above once the plastic cowling at the rear of the receiver is removed. That accomplished, the receiver can be reduced to its basic components for routine maintenance. The entire fire control system — the cross-bolt safety, hammer, hold-open button, AccuTrigger and sear — are contained within a poly module, which is integral with the trigger guard bow.

To ready the test gun for a little range work, we mounted a Bushnell 3-9×40 Rimfire scope using Weaver’s Grand Slam all-steel rings. The scope comes with three elevation turrets, one calibrated in standard ¼-inch graduations, while the other two are BDC-calibrated to the trajectory of the .22 LR and the .17 HMR. As it comes from the box, the standard turret is installed, and it’s the one we chose to use.

The .22 LR turret is calibrated to a 75-yard zero, which I feel is stretching the capabilities of that round. I prefer a 50-yard zero, which leaves me about a couple inches low at 75 and is easily compensated for with my hold.

Pre-installed Weaver bases for scopes are standard on the A22.

In addition to the BDC turrets, this scope is built on a one-piece, 1-inch tube; has multi-coated lenses; is waterproof/fogproof; has tool-less finger adjustments, a Euro-style fast focus eyepiece and a side parallax adjustment from 10 yards to infinity. This scope is a far cry from the cheap ¾-inch rimfire scopes I had when I was a young man!

The diet I chose for the test gun consisted of three Federal loads — the 40-grain solid, 40-grain Match HP, 40-grain bulk Value Pack — and CCI’s Green Tag Competition 40-grain. Over the course of firing some 220 rounds, there was not a single malfunction, which is impressive for one of the first production examples of a new design.

Obviously, the rotary magazine had to work flawlessly; however, charging the damn thing is a royal pain in the rear. If there’s a secret to it, I failed to discover it. I actually wanted to shoot a bit more because it’s really a fun gun, but after 22 loadings, my fingers were so sore I couldn’t continue.

I tried everything, and the only method that worked for me was to orient the cartridge 90 degrees to the right, and with the base of the case push the top round down and to the left, then rotate the cartridge to align with the loaded top rounds and push very hard on the case rim while trying to slide it rearward under the feed lips. Sometimes it actually worked, but most of the time it didn’t, hence the sore fingers. They have to make charging that magazine easier!

The AccuTrigger broke at 52 ounces as it came from the box, and checking it with the little wire-like adjustment tool showed it to be at its lower limit. There was noticeable creep to the pull, but it was smooth and not a problem. Actually, for a swinging hammer ignition, it was a pretty decent trigger. The hold-open lever at the front of the trigger guard bow is conveniently located, but the action does not lock open after the last shot.

Like many Savage rifles, this one comes with the AccuTrigger.

Accuracy was OK, but not phenomenal. The best-performing load was the Federal Premium 40-grain HP, which averaged right at 1 inch at 50 yards. The others averaged from 1-1/4 to 1-7/8 inches. With the addition of this .22 LR version, Savage now has a complete rimfire family: a .17 HMR, a .22 WMR (Magnum) and the LR. The Savage A22’s MSRP is $281.

Thanks to Gun Digest for this post. Click here to visit GunDigest.com.

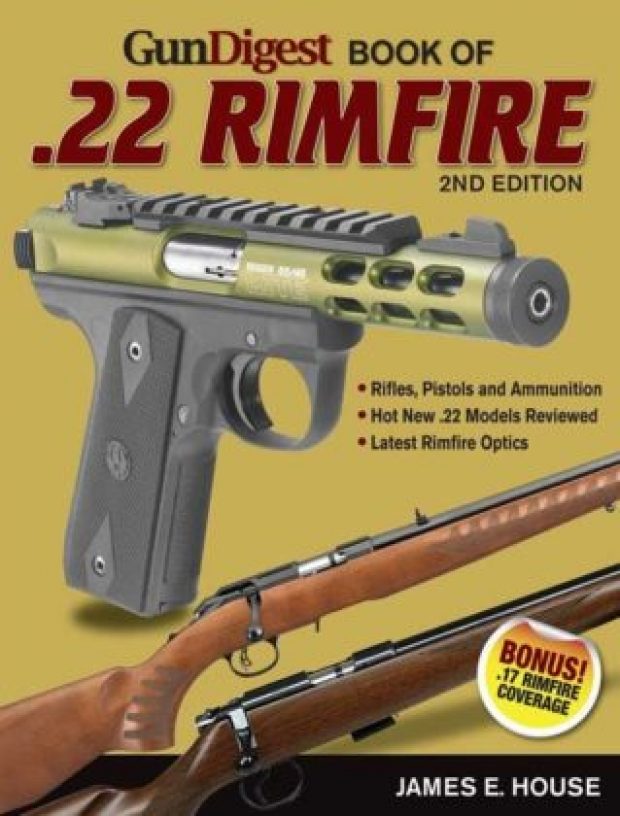

Better yet take a look at out: Gun Digest Book of .22 Rimfire, Second Edition.