For better or worse, The Washington Post has pretty much led the way in maintaining the narrative that advertisements of undisclosed origin (Russia) invaded social media in the 2016 presidential election, which was, of course, determined by Russia.

“Russian-aligned pages and profiles advertised their opposition to immigrants, targeting a range of users, including those who appear to like Fox News” the Post declared, parroting a report issued by Rep. Adam Schiff.

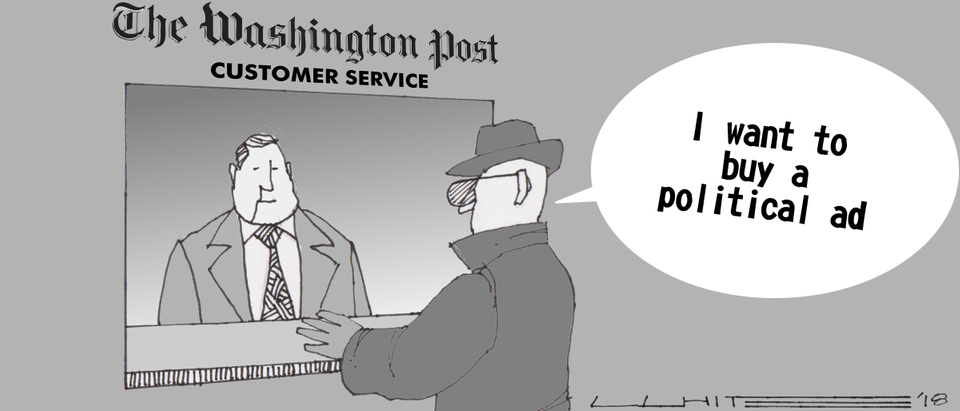

Underneath the slogan “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” the Post has run literally hundreds of editorials, news stories and unlabeled hybrids of the two decrying the “irresponsibility” of social media platforms for accepting these ads unthinkingly. After all, the logic goes, our cherished democracy must not be meddled with by anonymous funding. Of course, that is until The Washington Post is at risk of losing its share of revenue. Then it’s a different story.

The Maryland state legislature passed the Online Electioneering Transparency and Accountability Act last winter in response to revelations about Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. election. The law regulates targeted advertisements online paid for with Russian currency. Among other things, the regulation also requires digital platforms with more than 100,000 monthly visitors to maintain a list of and publish the names and contact information for any purchaser of a “qualifying paid digital communication,” along with the price paid. And last week, The Washington Post went to court to challenge that law.

You read that correctly. The Post (as well as The Baltimore Sun and some smaller local papers) is challenging a law that would require publishers to disclose the source and funding of political ads. This, despite its own dire headlines warning that “as midterm elections approach, a growing concern that the nation is not protected from Russian interference.”

I guess one nice thing about being a bazillionaire is that you can have a legion of underpaid ink-stained wretches constantly bleating “we wuz robbed,” and at the same time retain an army of well-paid and well-trained lawyers to argue that a law propelled by your own editorial pages is an unconstitutional infringement on your First Amendment rights and an unfair burden on your profitability. It’s good to be the King.

SPEAKING OF DARKNESS

It’s no secret that election seasons were traditionally lucrative for publishers. Not only candidates, but every union, PAC, Super-PAC, trade, trade association and gathering of tin-foil hat wearers contributed hundreds of millions of dollars in advertising revenue to newspapers. And here’s where it gets tricky: because of historical declines in circulation revenue of printed news, the same companies slowly and stumblingly but finally made their way to becoming online platforms.

The transition from revenue based on advertising to revenue derived from circulation via digital means has been a lifeline for legacy publishers. The Pew Research Center reported in June of last year that “following last year’s presidential election, some major U.S. newspapers reported a sharp jump in digital subscriptions, giving a boost to their overall circulation totals.”

The report also noted that “yearly financial statements show that The New York Times added more than 500,000 digital subscriptions in 2016 – a 47-percent year-over-year rise. The Wall Street Journal added more than 150,000 digital subscriptions, a 23-percent rise, according to audited statements produced by Dow Jones.”

And the Washington Post? None of your stinking business: “The Washington Post, as a private company, does not publish its financial results.” But the company’s chief revenue officer was kind enough to tell the very people it alleges to serve and inform that 2017 would be “our third straight year of double-digit revenue growth.” I don’t know about you, but I’m breathing a sigh of relief for Jeff Bezos. I was worried there for a minute.

IT’S THE PRINCIPLE OF THE THING

The 28-page Complaint filed in federal court is a well-crafted document that relies on long-standing First Amendment principles, namely, that “compelled speech” is more often than not unconstitutional. In short, the Supreme Court has held that requiring a speaker to publish things written by others, or against their own views violates the First Amendment. It’s for that reason that “equal time” types of laws generally fail.

The most famous of these cases was Miami Herald Publishing Co. v. Tornillo, in which a Florida statute required that if a newspaper criticized a candidate, that candidate would have a right to equal space in the same paper. Overturning that law, Justice Burger noted that:

“The clear implication has been that any such compulsion to publish that which ‘reason’ tells them should not be published” is unconstitutional. A responsible press is an undoubtedly desirable goal, but press responsibility is not mandated by the Constitution and like many other virtues it cannot be legislated.”

The ban on “compelled speech” has been applied in a wide variety of circumstances: pledging allegiance to the flag (West Virginia State Board of Education v. Barnette); circulation of political leaflets without disclosing sponsorship (McIntyre v. Ohio Elections Comm’n); and even the mandatory inclusion of LGBT marchers in a privately sponsored parade (Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston, Inc.).

At the same time, certain forms of “compelled speech” have been found constitutional when they achieve certain important government interests. Usually seen in the commercial sphere, where First Amendment rights exist but at a lower threshold, health warnings on cigarette packages, mandatory signage in restaurants reminding pregnant women that they are drinking for two, and warnings not to use wheelbarrows on the highway are examples of constitutionally acceptable “compelled speech.” The Federal Trade Commission and the Securities and Exchange Commission, along with the Food and Drug Administration are often in the “compelled speech” business.

The Post’s lawsuit is basically centered on the simple principle that “you don’t get to tell us what to say.” But the lawsuit goes farther: the Complaint also makes two other arguments, each of which is troubling, especially from an enterprise allegedly founded on the principle of transparency. It would seem that while “Democracy Dies in Darkness,” profitability thrives in it.

INFORMING THE PUBLIC IS TOO GREAT A BURDEN

The Washington Post will spare no expense finding out if the zippers on golf bags sold at Trump’s golf courses were made in China. They will fund (as is their right) the expenses of reporters to follow Stormy Daniels on her cross-country combination ethics lecture and pole-dancing tour. But in this lawsuit, the Post admits that:

“Each of the Publisher Plaintiffs, […] accept political advertising about candidates, prospective candidates, ballot questions, prospective ballot questions, and issues that might be deemed to relate to one or more of those topics. Publisher Plaintiffs do so both to generate income to support their operations, but also to provide a forum for core speech about political candidates, ballot questions and issues.”

The Post wraps itself in the flag of the public service they offer, arguing that the law “is likely to chill core political speech about candidates and issues because the online platforms (as well as the speakers themselves) will be uncertain as to whether speech is included and will refrain from speech to steer clear of the statutory restrictions and regulations.” It’s just too much work.

At the same time, it’s hard to believe that the same giant corporation that data-mines hundreds of millions of consumers and delivers narrowly targeted advertisements based on contents of readers’ past online purchases or browsing habits is somehow not capable of collecting or maintaining records of who is buying what ad and how much they paid for it.

HAVING IT BOTH WAYS

Reviewing the Complaint, one has to wonder whether the Post lawyers actually read the Post. In arguing that there are already sufficient laws to safeguard our elections, the lawsuit drops this stunning little nugget into their complaint: “[T]here is no evidence of a newspaper or other website being unwittingly manipulated by illegitimate foreign political advertising.” They might want to talk to their editors.

In September of 2017, the Post published a story headlined, “Russian operatives used Facebook ads to exploit America’s racial and religious divisions.” In May, the Post ran a story detailing 3,500 online ads that “show the scale of Russian manipulation.”

More damning yet, an editorial in the Post last year demanded that:

“It’s not yet clear how much influence Kremlin-funded advertisements had in shaping the 2016 election. But a full accounting of Russian interference requires that technology companies and the government both take a hard look at how those ads were allowed to run unnoticed.”

So, what are we to make of this? The Post is legally correct that “compelled speech” comes into a courtroom with a presumption of unconstitutionality. And looking at that case law, the Supreme Court has made it clear that there are certain circumstances of such national importance so crucial to the well-being of the democracy that the speech regulation in question might be justified. It is not a hard argument to make that the Post journalists and editorialists have loudly and frequently argued that phony ads or advertising manipulation rise to that level of import and had a meaningful impact on the defeat of their preferred candidate in 2016, and still continue to warn the public that the upcoming midterms may be similarly tainted.

The only conclusion I can come to is that while Mr. Bezos wants transparency in the democratic process, he does not want to pay his fair share of the cost for that transparency. Like I said, “it’s good to be the King.”

Charles Glasser (@MediaEthicsGuy) is the author of “The International Libel and Privacy Handbook”, teaches media ethics and law at New York University and also lectures globally and writes frequently about media and free speech issues for Instapundit and other outlets.

The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of The Daily Caller.