- New York’s case against Exxon isn’t about a global warming cover-up, but something more mundane.

- Attorney General Barbara Underwood is going after Exxon over its use of “proxy” prices for potential climate rules.

- “Today’s lawsuit is simply the latest in a string of attempts to target manufacturers in America,” one critic said.

New York’s lawsuit against ExxonMobil for allegedly misleading investors of the risks of global warming isn’t what one would think.

What started into an investigation into Exxon’s alleged attempts to “cover up” or downplay global warming has morphed into a lawsuit over the minutia of the company’s internal versus external valuations of “proxy” prices on carbon dioxide emissions from potential future regulations.

The premise of the state’s four-year investigation into Exxon stemmed from allegations it misled the public and investors by downplaying global warming risks through funding skeptics and opponents of global warming regulations. However, that’s not what Exxon is being sued for.

New York Attorney General Barbara Underwood filed suit against Exxon on Wednesday after a three-year investigation into the company’s representation of global warming risks to investors. The Democrat brought suit under the Martin Act, which gives her authority to prosecute securities fraud.

“As a result of Exxon’s fraud, the company was exposed to far greater risk from climate change regulations than investors were led to believe,” Underwood’s office wrote in its legal brief against Exxon, filed Wednesday.

The Exxon logo is displayed agove the floor of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) shortly after the opening bell in New York on Dec. 21, 2015. REUTERS/Lucas Jackson.

Underwood’s suit focuses on Exxon’s use of an internal “proxy” price for global warming regulations that was lower than prices put forward in reports to investors and the public. Exxon says it’s been internally pricing carbon dioxide emissions since 2007.

Underwood’s critics say this is because she’s “backed into a corner” after years of failing to find hard-hitting evidence that Exxon tried to cover up global warming science, despite millions of company documents being turned over to state investigators.

“Backed into a corner, New York AG Barbara Underwood was forced to show her cards today or accept the embarrassment of publicly folding after committing countless resources to a baseless investigation,” John Glennon wrote for the group Energy In Depth (EID), which is funded by the oil and gas industry. EID opposes New York’s suit against Exxon.

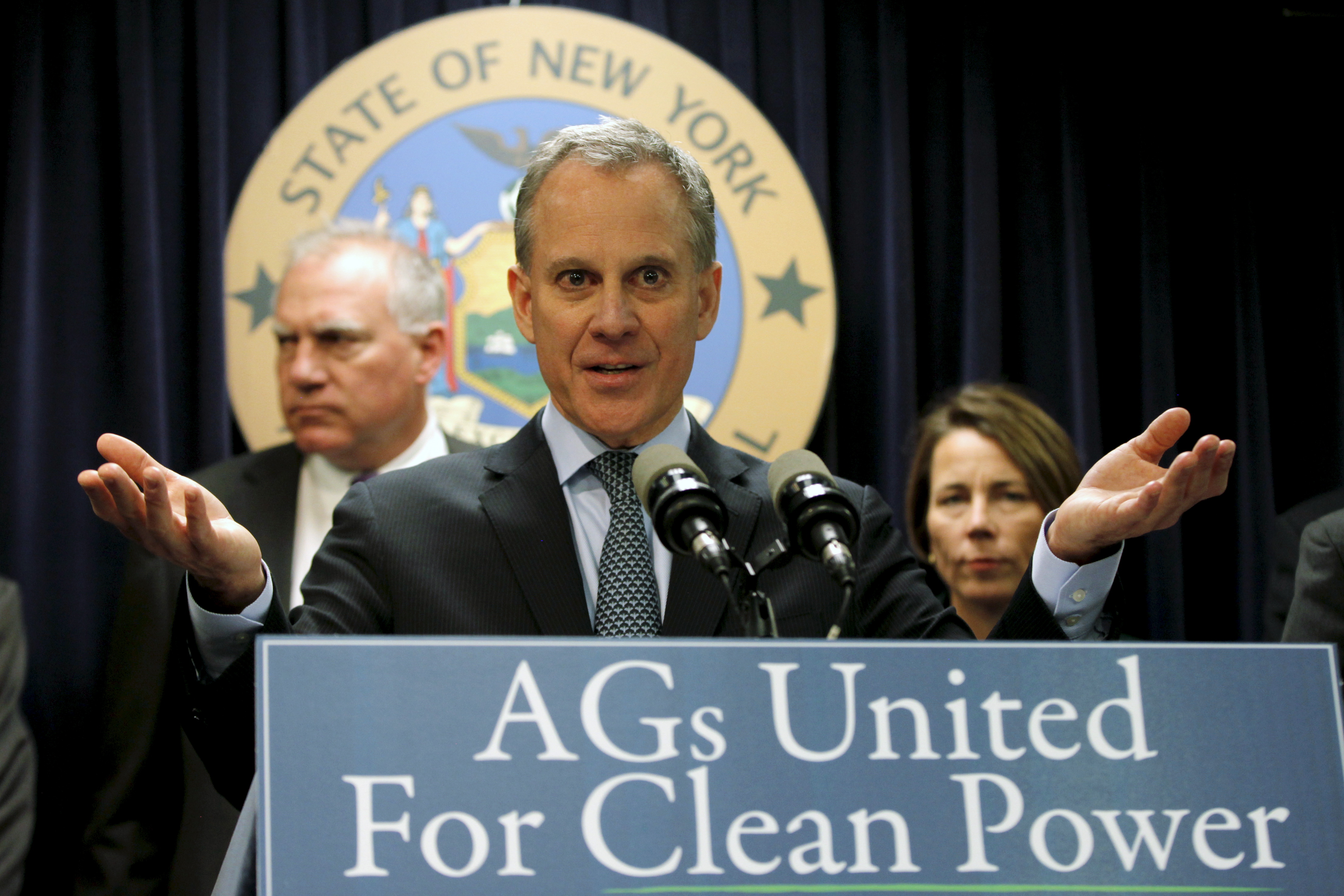

Indeed, Underwood’s suit seems radically different from the aim of former Attorney General Eric Schneiderman when he kicked off the investigation into Exxon in 2015.

Schneiderman and other state attorneys general going after Exxon subpoenaed records from dozens of conservative think tanks, scientists and policy experts opposed to Democratic policies to restrict carbon dioxide emissions.

New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman speaks at a news conference with other U.S. State Attorney’s General to announce a state-based effort to combat climate change in the Manhattan borough of New York City, March 29, 2016. REUTERS/Mike Segar.

In fact, The New York Times’ 2015 report that broke the news of Schneiderman’s investigation “noted that any potential fraud prosecution might depend on exactly how big a role company executives can be shown to have played in directing campaigns of climate denial.”

The investigation was initially about “the company made to investors about climate risks as recently as this year were consistent with the company’s own long-running scientific research,” The Times reported in 2015. That also included Exxon’s funding “outside groups that sought to undermine climate science, even as its in-house scientists were outlining the potential consequences — and uncertainties — to company executives,” The Times noted.

Schneiderman’s investigation was aided by reports from liberal journalists with Columbia University and InsideClimate News the company worked to downplay the potential risks of global warming. Those reports alleged that Exxon “knew” the dangers of global warming for decades, but funded groups and worked to downplay risks of a changing climate.

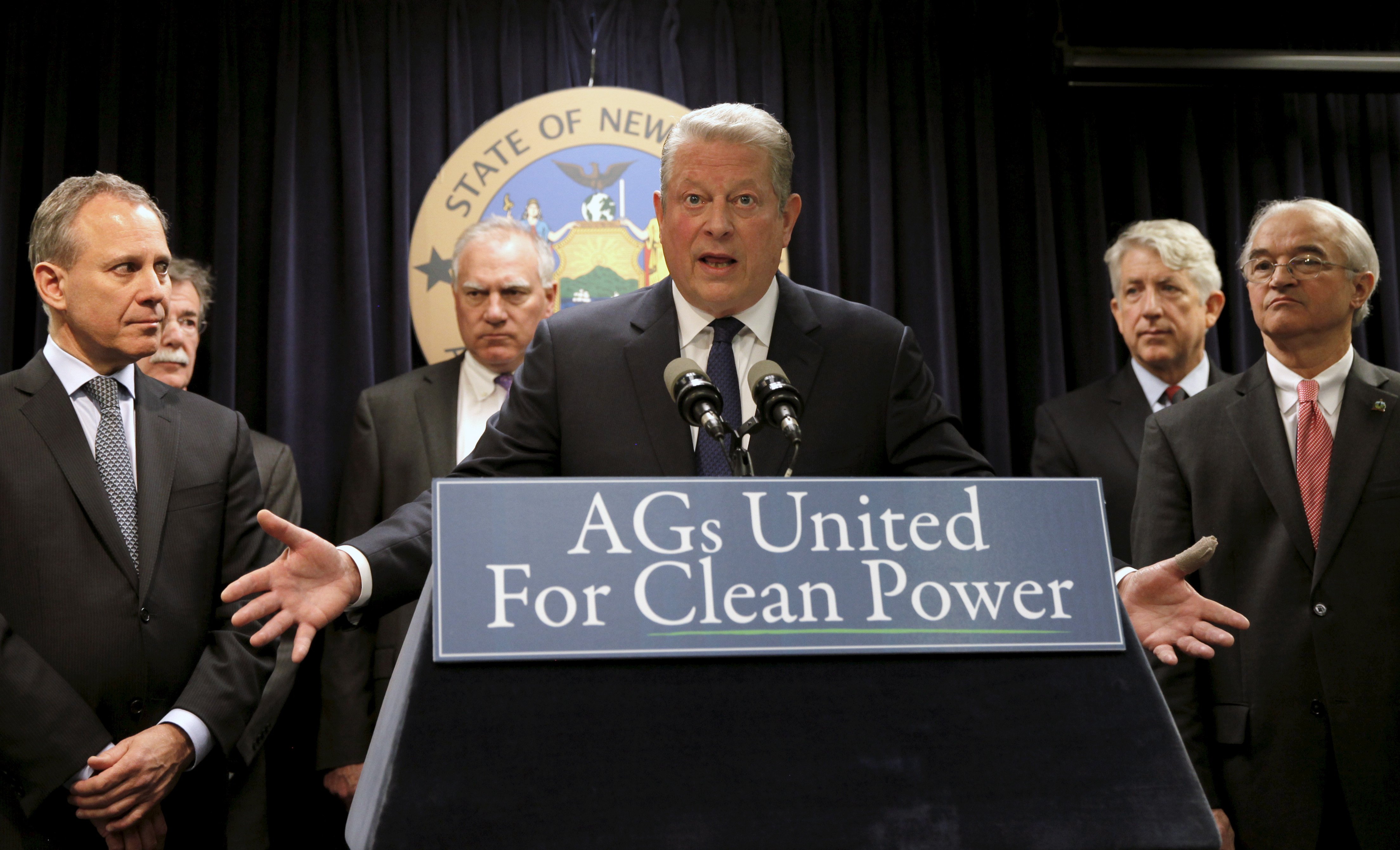

Schneiderman, who resigned earlier this year, and his allies, including former Vice President Al Gore, compared Exxon’s actions to those of the tobacco industry in trying to downplay research that their products were harmful — in this case, research that fossil fuels could be fueling catastrophic warming.

Prominent Democrats and environmentalists called for investigating Exxon and other oil companies for allegedly covering up the risks global warming. Among those calling for investigations were Vermont Independent Sen. Bernie Sanders and Massachusetts Democratic Sen. Elizabeth Warren.

U.S. Senator Elizabeth Warren puts her arm around U.S. Senator Bernie Sanders after introducing him at a Our Revolution rally in Boston, Massachusetts, U.S. March 31, 2017. REUTERS/Mary Schwalm.

Exxon, conservative groups and Republican attorneys general fought back through the courts and media, calling Schneiderman’s investigation a witch hunt that threatened free speech rights.

But in 2016, Schneiderman flipped the script, and “focused less on the distant past than on relatively recent statements by Exxon Mobil related to climate change and what it means for the company’s future,” The New York Times reported at the time.

The Times’ 2016 article noted that “[e]arly on, [Schneiderman’s] office demanded extensive emails, financial records and other documents from the oil company, leaving many observers with the impression that a deeper look into the company’s past was the focus of the investigation,” before changing it to the future.

Schneiderman began harping in 2017 on Exxon’s use of a “proxy” price for carbon dioxide regulations. Exxon uses proxy carbon prices to reflect the cost of future regulations governments may place on emissions. In legal filings, Schneiderman said Exxon internally used a “lower GHG taxes instead of its publicly-stated proxy costs.”

Underwood’s lawsuit against Exxon seems to continue where Schneiderman left off in alleging the oil giant presented climate risks to the public substantially larger than it considered internally.

“For years, to the extent that Exxon applied any proxy cost to its projected GHG emissions, it applied significantly lower proxy costs than those represented to investors,” reads Underwood’s filing against Exxon.

For example, Exxon’s public reports estimate the costs of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries’ climate policies will come out to $80 per ton of carbon dioxide by 2040, but its internal reports only priced such policies at $60 per ton.

In some cases, Exxon “did not apply any proxy costs to its projected GHG emissions in its base economic projections prior to 2016,” reads the legal filing. Underwood said, “Exxon applied only the existing GHG-related costs presently imposed by governments (i.e., legislated costs), and assumed that those existing costs would remain in effect, at existing levels,” which contradicts the company’s public reports.

By using a lower internal “proxy” price for climate regulations, Underwood alleges Exxon “was exposed to far greater risk from climate change regulations than investors were led to believe.” Underwood also alleges lower or non-existent proxy costs were also applied to Exxon’s projections of resource reserves, major asset values and future transportation demand.

Former U.S. Vice President Al Gore (C) speaks at a news conference with New York Attorney General Eric Schneiderman (L), Vermont Attorney General William Sorrell (R) and other U.S. State Attorney’s General to announce a state-based effort to combat climate change in the Manhattan borough of New York City, March 29, 2016. REUTERS/Mike Segar.

Environmentalists and green lawyers cheered New York’s suit against Exxon, with one prominent activist calling it “huge news.” Gore was among those environmentalists championing Underwood’s legal action.

Glad to see @NewYorkStateAG has moved forward with a lawsuit alleging that Exxon Mobil fraudulently covered up the impacts of the climate crisis. Companies must tell investors the truth about this growing threat and the “Carbon Bubble.” https://t.co/ABmQwao9FH

— Al Gore (@algore) October 24, 2018

Businesses and conservative groups disagreed.

“Today’s lawsuit is simply the latest in a string of attempts to target manufacturers in America,” Lindsey de la Torre, executive director of the industry-funded Manufacturers’ Accountability Project, said in an emailed statement.

“Rather than focus on productive solutions, Attorney General Underwood moved ahead with this politically-motivated lawsuit, wasting even more taxpayer resources in an effort to infringe on manufacturers’ First Amendment rights,” de la Torre said.

Underwood’s office did not respond to The Daily Caller News Foundation’s request for comment.

Follow Michael on Facebook and Twitter

All content created by the Daily Caller News Foundation, an independent and nonpartisan newswire service, is available without charge to any legitimate news publisher that can provide a large audience. All republished articles must include our logo, our reporter’s byline and their DCNF affiliation. For any questions about our guidelines or partnering with us, please contact licensing@dailycallernewsfoundation.org.