I recently received a call that my old friend and mentor, Peter Collier, had died. David Horowitz, Peter’s long-time co-conspirator and best friend had reached out to me a few weeks earlier to tell me that Peter was extremely sick. He had been diagnosed with an aggressive form of leukemia last summer and the prescribed regimen of chemotherapy had poisoned his internal organs. Peter was a man of faith and David, knowing of our relationship and that I was now a pastor, asked if I would travel to Northern California to be with him. Sadly, Peter’s body gave out before I could get there. He died on All Saints Day.

If you don’t know who Peter Collier is, his work and life have touched your own, I assure you. Collier and Horowitz were 60’s radicals and the former editors of Ramparts magazine, the flagship publication of the Vietnam-era New Left. Peter and David had their fingers, if not their whole fists, in every American-made Marxist pie baked back in those days.

Peter first met David when they were both studying English at Berkeley in the early 60s. They quickly formed a relationship that would be held together for decades by the covalent bonds of friendship, ideology, mutual enemies, tragedy, commercial success and an eventual longing to undo the damage they did as young radicals. (RELATED: My Free Speech At Berkeley — Not)

Like all great duos, their friendship was ironic. David was the Mick Jagger to Peter’s Keith Richards. They loved, fought, challenged and honed each other to greatness. While each was accomplished in their own right, it is rare to hear either of their names mentioned in a sentence without the other’s.

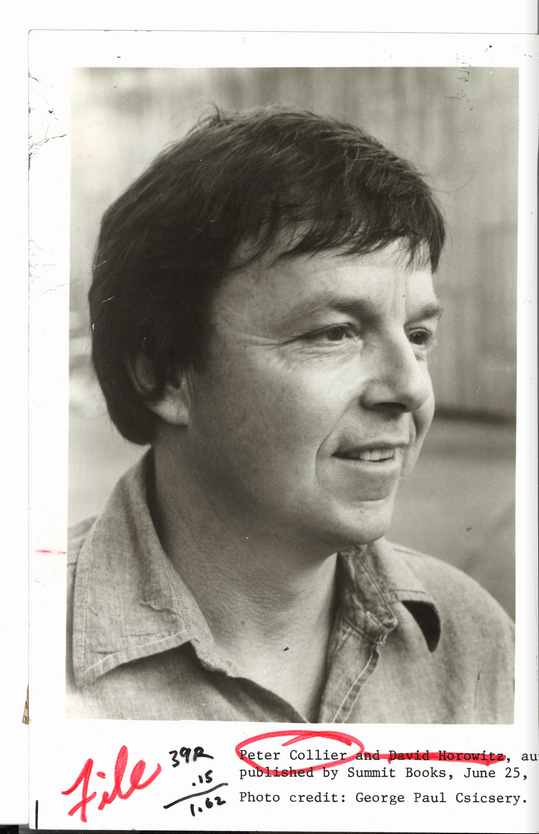

Image courtesy Encounter Books

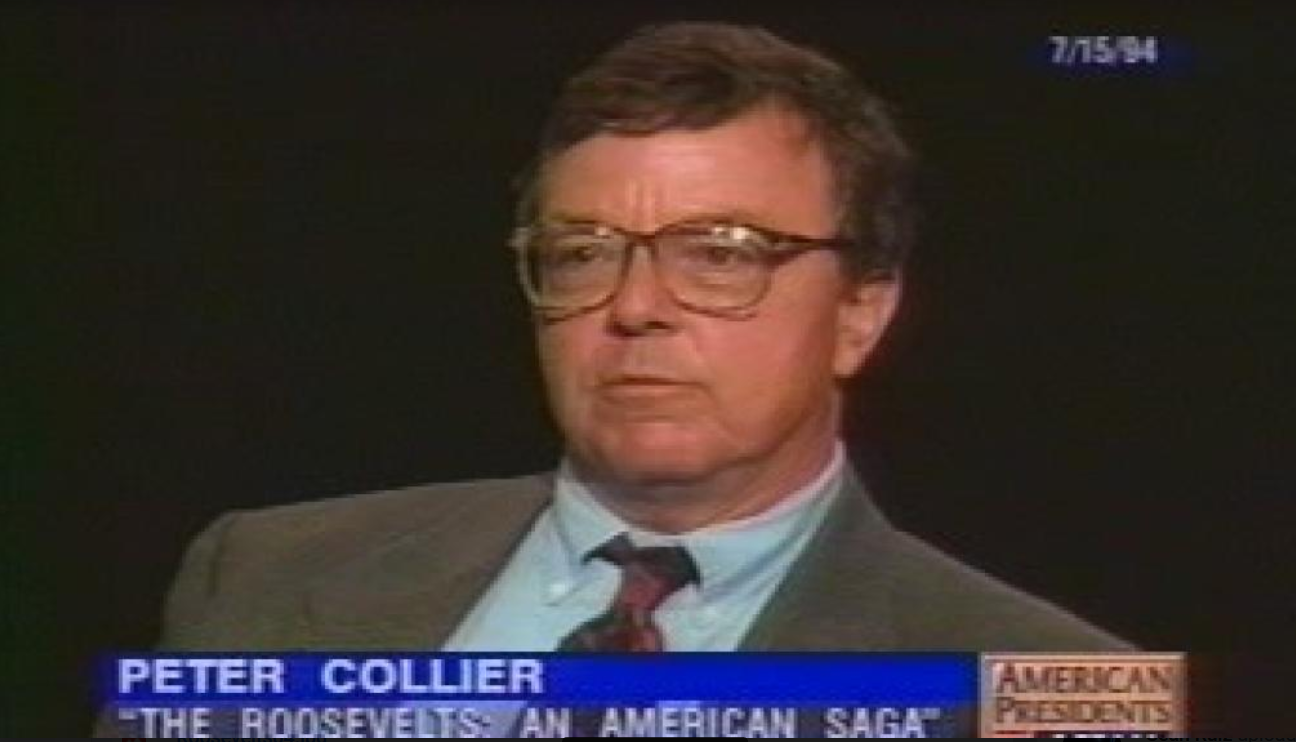

Peter was a Los Angeles, California bred son of normalcy and a walking paradox. His father was an insurance salesman and his mother a flight attendant but Peter carved his professional path out of the cul-de-sac and into the oncoming political traffic. Peter was a nuanced intellectual with a sensitive and lyrical writing style, but he could be a blunt force instrument when writing about his adversaries. He was a private person who lived out his adult life in the quiet foothills of the Tahoe National Forest, but much of his career was spent making journalistic forays into political and cultural combat zones. He wrote long, thoughtful biographies about prominent family dynasties and short, stinging hit-pieces about academics of whom most have never heard. (RELATED: Jeane Kirkpatrick gets a second look)

David was a New Yorker from Queens, Jewish and a self-described Red Diaper Baby. His parents were school teachers, atheists and communists who held secret late-night party meetings in their home. David’s beliefs were forged in the crucible of Stalin-era Marxism and refined in the fires of Berkley radicalism. As a result, he grew up to become the 5’4” ideological cage-fighter he is now famous for being.

Peter was the Yin to David’s Yang and when they eventually joined forces at Ramparts magazine — for better or worse — became the philosophical torch bearers for the left-side of their generation. That is, until the acceptable collateral damage incurred in the interest of the larger good became devastating personal loss.

In 1974, Peter and David helped a friend and former Ramparts employee by the name of Betty Van Patter find a job as a bookkeeper with the Black Panthers. Betty soon discovered a number of financial discrepancies and naively made them known. One night she received a mysterious phone call from an unknown individual asking her to meet at a local bar. She walked in, was greeted by a messenger who handed her a note and then followed him out the door. Nobody saw her alive again. Five weeks later Betty’s broken body was discovered floating in the San Francisco Bay.

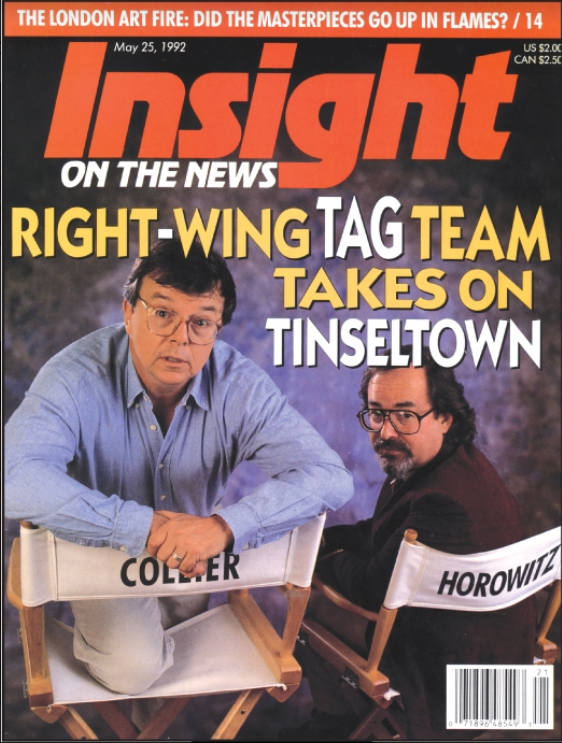

Image courtesy David Horowitz

Peter and David suspected this was the work of the Panthers and began to ask questions. It became apparent to them (a belief they hold/held to the current day) that the Panthers were responsible for Betty’s death. Unable to get help from a police force they had spent years trying to hobble, they quickly extracted themselves from the only political ecosystem they knew. It had become too dangerous.

This began a season during which they began to challenge their political and personal assumptions. In time they quietly transformed into the photographic negatives of their former selves, adopting a conservatism that embraced the very country and institutions they had worked so hard to undermine.

In 1989, Peter and David released their book, Destructive Generation: Second Thoughts About The Sixties. Destructive Generation was equal parts memoir, expose, political statement and confession. It was a book that shredded the romantic caricatures of people like Huey Newton, Jane Fonda and places like Berkeley. What made the book so powerful is that they also shredded themselves. They owned where they had been wrong and how their convictions had blinded them to the dark realities swirling around them. (RELATED: Jane Fonda Arrested In Washington D.C. While Protesting)

I first read Destructive Generation in 1990. I was twenty years old attending a small liberal college in New England. I had no idea what I really believed about pretty much anything. Like most people my age, I had been been caught in the current of twenty-something liberalism. I had half-swallowed the hook baited with the mythology of the movements from which Peter and David emerged. If I’m honest, my flirtations with those things were more about trying to establish a personal identity than any real conviction. In the end, those flirtations only bred more self-doubt. It was during that season that someone gave me a copy of Destructive Generation.

What Whittaker Chambers’ book, Witness, was to the post World War II generation, Destructive Generation was to me. It took me down to the ideological studs. As a memoir it was captivating. As an expose it showed the duplicity of people and organizations I had previously seen as unambiguously virtuous. Destructive Generation taught me that ideas have consequences. It illustrated the dangers of doctrines that elevated the state above the individual and displayed the body count of movements whose success depends on perfecting humanity.

As a confession, Peter and David’s writing had theological undertones that nudged against truths that would eventually alter my world. They implicitly embraced the fallenness of the human heart while exemplifying the consequences of ignoring that truth.

As a result, Peter and David didn’t just reframe my understanding of the world, they reframed my understanding of myself. I didn’t have the language for it back then, but the self-righteous and duplicitous postures that Peter and David so brilliantly wrote about weren’t just true of them and their former comrades; I intuitively knew they were true of me.

Image courtesy David Horowitz

As sobering as this sounds, it is hindsight and I am overlaying 51 years of perspective on this time in my life. Realizing what is true is very different than being mature in that truth. By the time I graduated from college, I was drunk on my new political beliefs. Like most who have any sort of ideological, political or theological re-birth, the intensity of my zeal was inversely proportionate to the depth of my self-awareness. I was obnoxious and probably should have been locked in a closet for a year to calm down, but taking things slow has never been my strong suit. When it came time for me to find a job (I wanted to be a journalist), I reached out to the two people for whom taking it slow seemed to be a liability: Peter and David.

I had heard they were preparing to launch a new magazine called Heterodoxy. This was the early 90’s and the phrase, political correctness, was newer and used mostly by think-tank and policy wonks. Most people (including myself) were unaware that many college campuses had become incubation chambers for political insanity. Peter and David saw it, knew the trajectory of such things and created Heterodoxy to push back.

They thought conservatives were too measured, polite and lacked the resolve to kick the cultural ant-pile with enough force and consistency to kill what would crawl out of the ground. With Heterodoxy, they were going to create a conservative magazine that captured the look, feel and boot-to-head ethos of Ramparts. As Peter once said, they were going to name names and hold people accountable. Heterodoxy’s self-descriptor was “the cultural equivalent of a drive-by shooting.” That pretty much summed it up. I sent David and Peter a letter on a Monday, got a phone call offering me a job that Thursday and was in a car driving from Washington to Los Angeles the following week. (RELATED: Book claims Marilyn Monroe told Jackie about JFK affair)

I was 22 years old when I began working there. It was a start-up magazine, so our offices were in David’s one-story ranch house in Studio City. Peter lived in Northern California, so most of our interactions were over the phone. He was like Charlie in the old Charlie’s Angel’s episodes; a faceless voice loaded with quiet personality that endeared me to him immediately.

Heterodoxy was everything it set out to be. The first issue ran a lead story about a new academic department somewhere in the University of California system created to challenge the notion of gender and heterosexuality as a patriarchal construct. I still remember trying to explain to my sweet, southern mother why the first issue of Heterodoxy featured a giant image of Karl Marx wearing lingerie and holding a bullwhip on the cover.

Image courtesy David Horowitz

Heterodoxy was smart, insightful but it was extremely caustic. I quickly learned that when you attack the politically pious (and I include myself among those ranks back in those days) it only emboldens them. If you make fun of them, their heads will come off on a spring. We did the latter ruthlessly. As a result, we received so many death threats and so much hate mail that by the end of my second year, David took me to a gun shop where he purchased a 9mm Glock. At his request, I kept it in my desk drawer. I was too young and dumb to digest the implications of a work environment that now had me packing heat. It should have caused me to pump the breaks, but at this time of my life I was too wrapped in my own bravado and thought it was awesome. (RELATED: Glock 17: Best 9mm for concealed carry?)

We all took the backlash as evidence we were making a difference. I would never let onto it at the time, but it was too much for me. Like so many other things in my life up to that point, I let who I thought I should be interfere with who I really was. I was not a pugilist and didn’t have the constitution to knock heads for a living. I hate conflict, and working in an environment that existed to create it took its toll. I wrote off my increasing anxiety and the bad choices I made in response to it as work stress. I was so far from the faith and world from which I came and would eventually end up in, but I now know that God used that experience and my relationship with Peter to begin my journey home.

Things were going well for me at work. I had been working at Heterodoxy for three months and Peter assigned me my first article. I have no real memory of what I wrote about, but I do remember spending an inordinate number of hours on the piece with a thesaurus by my side. I wanted to impress him, so I shoe-horned as many $25 words into the piece that I could. It didn’t work.

When Peter sent me the final copy for the final layout via modem (this was before email), I ran to my office, shut my door and read my piece. Not a single original word I had written remained. I was crestfallen. This was a body blow, but it also began to break the hard packed solid of my ego so something good could grow.

Peter and I spoke multiple times a day. He was patient and kind. I learned more sitting at his feet (and David’s) than I did in four years of college. He taught me how to think, how to reason, the power of a story and how using big words in gratuitous ways makes you sound illiterate.

Image courtesy David Horowitz

One morning I called Peter at our regular time but he didn’t answer. He didn’t call me back which was uncharacteristic when we were approaching a deadline. When I got him on the phone that afternoon I could tell there was something wrong. Peter was a private person and to me he was the platonic form of male confidence. I never felt it my place to pry into his personal life. Hearing the tone of his voice I forgot myself and risked the question, “Hey, man. You ok?”

Peter was slow to respond but proceeded to tell me that he was not. One of his sons had just been diagnosed with an illness that was life altering, chronic and for which there was no immediate cure. He was distraught and struggled to find words as he began to share his fear and sense of helplessness. I didn’t know much back then, but I knew I was on holy ground; a place to remove my shoes and walk gently. I just listened.

In the course of the coming weeks our conversations continued and Peter became increasingly vulnerable. I did too. This was a time in my life when I was questioning my faith in God, but this tragedy — as tragedy often does — ushered in a season where Peter began to rediscover his. We spent hours talking about faith, Jesus, grace and what it meant to reconcile God’s goodness in a world where sons get sick and we keep guns in our desk drawers.

In those conversations we both felt an ironic hope. It was ironic because we experienced hope at a time that neither of us saw the resolution of our problems. Peter’s son was still sick and I was still in the throes of a weapons-grade identity crisis. It was hopeful because while those problems had not been resolved we both felt un-alone. Feeling un-alone in a time of crisis is the grand reminder that goodness is still in play. This isn’t some trite platitude. It is the reality of how God designed and moves in our hearts.

Jesus calls Himself Emmanuel, God with us, for a reason. He knows the deepest cry of our souls. It is Adam’s cry in the bush, the Israelites in the desert and Jesus’ on the cross: Why have you forsaken me? The gospel doesn’t promise the immediate resolution of our problems. Nowhere in scripture are we promised a solid 401(k) or better gas mileage. In fact, it promises that in this world we will have trouble (John 16:33). But it also says that we can take heart because Christ has overcome the world. That means a lot of things, but on a most basic level it underscores a truth about God’s movement in the world: Pain and chaos are not evidence of His absence, they are the arena in which He moves. My conversations with Peter were my first real taste of that. It was a taste that would linger for years to come and one that helped steer my path to the ministry.

Image courtesy David Horowitz

Last week I flew to Florida to speak at Peter’s memorial service. I had not seen him or David in many years, but I was very glad to be given the opportunity to honor my friend. I am not political anymore. Sure, I have my opinions, but I have long since recused myself from the fight. Over the years I have spent a lot of time thinking about my time working with Peter and David, wondering what it had all been about.

As I prepared what I was going to say at Peter’s memorial I felt that question give way to some semblance of an answer and deep gratitude. I was grateful that I serve a God who, twenty seven years ago, dragged an arrogant and scared twenty two year old kid across the country and into a world where he would be way over his head. I am grateful for what I learned during that time, the doors that experience would open as well as for the ways I was brought to the end of myself. I am grateful that God brought a kind man named Peter Collier into my life and that Peter was willing to invite me into his. But most of all I am grateful for the friendship God provided during that time and all the ways it bred hope in life’s darker hours. What was my time working with Peter about? For me it was about a real-time experience of a God unwilling to let us navigate the dim hallways of this world alone. It is there that he shows us His glory in the ruin. Heterodoxy, indeed.

Peter, well done good and faithful servant. Rest in His peace.

The Rev. Billy Cerveny is a pastor in Nashville, TN and the Executive Director of Redbird. www.redbirdnashville.com