As the Minneapolis Police Department has been at the center of national attention following the death of George Floyd, the role of police unions, too, has been thrown into sharp relief as the city and state moves to enact reforms and accountability measures.

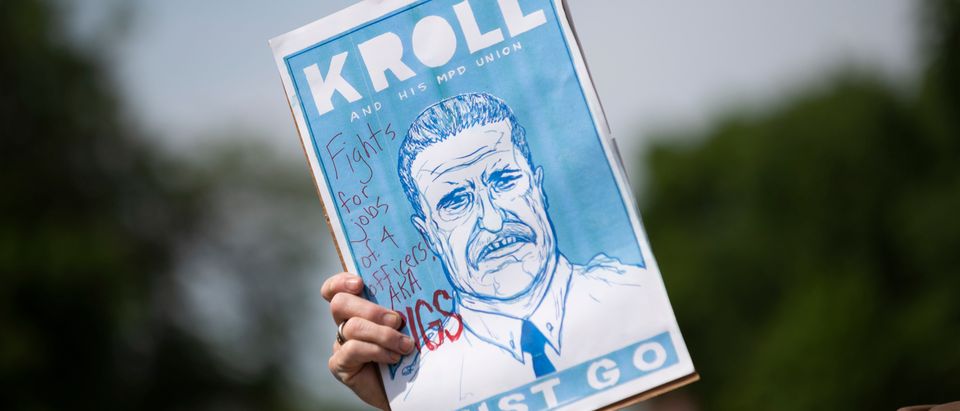

Derek Chauvin, the former officer who is charged with second-degree murder for Floyd’s killing, was fired after Floyd’s death. However, the union Minneapolis Police Federation president Lt. Bob Kroll said he was fighting to help Chauvin and the three other officers charged with aiding and abetting get their jobs back.

Former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin poses for a mugshot after being charged in the death of George Floyd . (Photo by Ramsey County Sheriff’s Office via Getty Images)

Kroll has also staunchly defended the officers, calling George Floyd a “violent criminal” and describing those protesting in the wake of his death as “terrorists.” Floyd had gone to prison for armed robbery in Houston in 2009, but was not armed or suspected of a violent crime when he was detained, according to the Guardian.

Teeming with power, police unions are often the obstacles keeping departments from initiating any kind of reforms or holding officers accountable. A former Minneapolis police chief, Janeé Harteau, told the Guardian that she had battled Kroll repeatedly over the years in an effort to reform the department, but the police union or federation is often more powerful than the police chief.

“The police federation has historically had more influence over police culture than any police chief ever could,” said Harteau. “I was fought at every turn from bringing body cameras to the police department, to having implicit bias training, to professional development processes and having some more consistency in promotions.”

Police unions aggressively protect members accused of misconduct, like in the recent incident involving officers who pushed a 75-year-old man to the ground in Buffalo. The president of the police union said the union stood behind the officers “100 percent,” according to the New York Times, and that the officers “were simply following orders.”

This is the case for police departments across the country, where unions by default defend officers in nearly every scenario, including a civilian death caused by deadly force.

When 17-year-old Laquan McDonald was killed by officer Jason Van Dyke, it was revealed that Van Dyke had a history of complaints that he was left unaccountable for due to a “code of silence” about misconduct that is prevalent in labor agreements, the New York Times reported in regards to a report published by a Chicago task force.

Police unions also pay for officers who are accused of misconducts’ legal representation, making officers more confident that they’ll dodge criminal charges, according to Vox.

A general view outside the Second Precinct Police Station on June 9, 2020 in Minneapolis, Minnesota. (Photo by Stephen Maturen/Getty Images)

As Minneapolis seeks to reform its police department, Mayor Jacob Frey has emphasized the obstacles police unions create when the city seeks to implement reforms, saying that previous probes had been “thwarted by police union protections and laws that severely limit accountability among police departments.”

After an investigation into the department, the police chief announced it would be withdrawing from union contract negotiations amid concerns that the police union was hindering accountability and reform measures. (RELATED: Minneapolis Police Department To Withdraw From Union Negotiations)

But even when rank-and-file officers don’t agree with the union or want to enact reform, they often can’t compete with union power.

“[Y]ou may have a group of black police officers who feel very differently than the union does, but those folks don’t have bargaining power,” Phillip Goff, director of the UCLA’s Center for Policing Equity, told Vox. “They don’t have the political power that the official bargaining union does.”

The collective bargaining power makes it nearly impossible for the department to investigate or punish officers for misconduct, with barriers built into contracts.

![Former Minneapolis police officers (clockwise from top left) Derek Chauvin, Tou Thao, Thomas Lane and J. Alexander Kueng poses in a combination of booking photographs from the Minnesota Department of Corrections and Hennepin County Jail in Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. [Minnesota Department of Corrections and Hennepin County Sheriff's Office/Handout via REUTERS]](https://cdn01.dailycaller.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/RTS3AIKW.jpg)

Former Minneapolis police officers (clockwise from top left) Derek Chauvin, Tou Thao, Thomas Lane and J. Alexander Kueng poses in a combination of booking photographs from the Minnesota Department of Corrections and Hennepin County Jail in Minneapolis, Minnesota, U.S. [Minnesota Department of Corrections and Hennepin County Sheriff’s Office/Handout via REUTERS]

When police chief Medaria Arradondo fired an officer who was caught on camera beating a handcuffed man on the ground, the police union filed a lawsuit alleging the city violated its contract with the union and forced the city to agree to rehire the officer and pay him lost wages, Courier Newsroom reported.

Police unions are required under the duty of fair representation covered by the National Labor Relations Act and state laws to protect their members, which includes giving them legal aid and support in job negotiations, according to Vox.

In cases of misconduct, union leaders will often reference this obligation. “It’s our legal responsibility to represent our members,” James Pasco, legislative director of the union Fraternal Order of Police (FOP) told Vox. “It’s our job.”

As Minneapolis grapples with the future of law enforcement in the city, the police chief has expressed the need for reconciliation when moving forward. When asked if Kroll will be a part of the solution, Arradondo said “I care deeply about this city…and we have to look into our hearts and what’s in our best interest. I hope he does the same,” according to Fox 9.