By Jeff Johnston, Shooting Illustrated

The world is witnessing a golden age of tactical shotguns right now, and IWI’s Tavor TS12 represents the cutting edge of new-shotgun design in a market dominated since 1887 by single-magazine-tube guns. Some such designs are even gaining favor. Why?

High-capacity, bullpup-style shotguns offer some obvious advantages over traditional models, including a shorter overall length for greater maneuverability and the ability to put more rounds downrange before reloading. IWI’s TS12 offers these traits in spades, and it also has something else civilian consumers want: Badass looks.

But, the TS12’s uniqueness and devotion to correcting traditional scatterguns’ downsides did not come without a few downsides of its own. Here we’ll take an in-depth look at all facets of this fascinating new shotgun.

What-in-the-Area-51 is It, and How Does it Work?

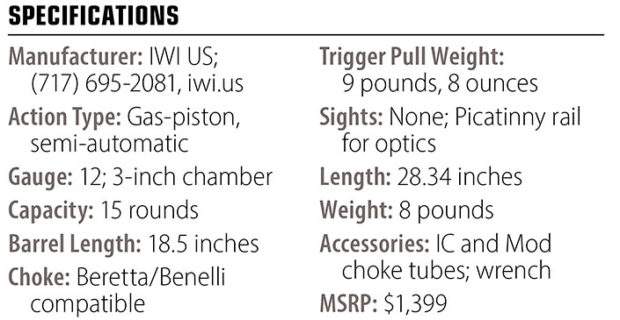

At the heart of the TS12 is a short-stroke, piston-driven, gas-action semi-automatic shotgun, but that’s about where its similarities with traditional shotguns end. The gun’s central-design feature is its patented, three-tube magazine (each tube holds five 2¾-inch shells) that can be rotated into battery as each tube runs dry or another type of shell is needed.

As each loaded tube is rotated in line with the bolt, a shell is automatically released onto the carrier before being elevated and shoved into the chamber by the bolt that’s returned into battery via a recoil-return spring that’s part of the bolt assembly and hidden by the buttstock. As the bolt meets the barrel extension, it slides up an eighth of an inch to lock onto it.

When the shotgun is fired, gas enters ports in the barrel, then goes up into the gas regulator, where it is redirected and driven rearward, striking a piston that in turn strikes a 6.75-inch extension (called a skidder tube) that places sudden rearward pressure on the bolt. The bolt assembly is forced back and downward, so it is liberated from the barrel extension just before being slung backward, thereby extracting and ejecting the spent shell. The entire bolt assembly then slides rearward on a stationary, stainless steel bridge bar that is a continuation of the barrel extension and anchored by the buttpad. The bolt is then returned into battery to complete the cycle.

–

While the mechanics of TS12’s action are not revolutionary, its design in terms of how it all fits and melds into one seemingly seamless gun is. The bullpup design that places the receiver in the buttstock allows this semi-automatic shotgun to utilize a non-NFA 18.5-inch 4041 steel barrel, yet still boast an overall length of just 28.34-inches, or approximately a foot shorter than the average, traditional shotgun. These two features alone grant the TS12 15 rounds of 12-gauge firepower from an 8-pound platform that’s easy to wield around corners, keep at the ready or transport when not in use.

Amazing Engineering

If you’ve glimpsed the TS12, you know it looks like it’s right out of an alien spacecraft or a battle-for-earth video game, what with its angular profile, straight-line stock and 90-percent black polymer build. While it’s true that this gun’s very best trait may be its stunning, futuristic looks, the engineering that went into developing it is nothing short of fantastical.

In fact, I’m hard-pressed to name a firearm of any make in any genre having more complex design elements, and for this alone, IWI should be commended. Every part is machined or molded for a perfect modular fit; every element has a purpose. What’s perhaps most impressive is that, despite the complexity of working parts, the gun can be field stripped without the use of tools.

A simple push of a recessed, spring-loaded button in the buttstock allows it to slide on a dovetail that in turn releases spring tension on a hexagonal nut (that also serves as a sling stud) so it can be removed by hand, thereby unlocking it from the receiver and allowing the receiver and bolt to be removed and cleaned. The entire process is as nifty as finding a hidden latch in a bookshelf that unlocks a castle’s secrets.

–

At the muzzle end, a shotgun-style barrel nut secures the fore-end to the barrel assembly. Once removed, the user gains access to the gas regulator, the barrel and the magazine-tube system. Further stripping requires one simple tool.

The body of the gun—I’ll call it the chassis receiver, including the buttstock’s lower assembly, pistol grip, magazine-tube guard and charging handle frame—is a one-piece, molded, reinforced polymer frame onto which an 16 inch, mil-spec 1913 Picatinny rail is attached.

The real marvel, however, is in the gun’s loading process. As each mag tube is emptied and the bolt is locked rearward on an empty chamber, the shooter uses the backside of their trigger finger to press forward the mag-tube-unlocking button, allowing it to rotate as clockwise or counterclockwise pressure is applied by the shooter’s support hand. When the fresh mag aligns with the receiver’s feeding hole, a shell is forced onto the carrier, where it trips the bolt-release button, thereby automatically releasing the bolt and chambering the round. The shooter is now ready to shoot five more shells before rotating to the next tube.

While one tube is in battery, the other two can be loaded from either the right or left loading port individually or simultaneously. Furthermore, either tube can also be unloaded from either port by pushing its shell-release lever. Then, rather than springing out and hitting the shooter’s face and/or falling to the ground, each ejected shell is held until the shooter is ready to manually remove them or replace them with a shell of choice.

The TS12 features a manual safety that actually disengages the trigger assembly rather than merely blocking it. A full-polymer handguard protects the trigger as well as the entire hand. The shotgun comes with a cylinder-bore, Beretta/Benelli-style removable choke tube. It has four attachment points for sling swivel studs. But, most notably, its gas regulator features a knurled knob and two positions so the user can choose between “H” (for 3-inch magnum or high-power loads) and “L” for standard 2 3/4-inch or low-power loads.

The regulator limits gas for the high-power loads while maximizing piston push when set to “L.” It can be accessed through the handguard by using a simple flathead screwdriver. A non-reciprocating charging handle juts out from the left side of the receiver, and although the instruction manual says that it can be converted to left-handed use by the factory only, it is easily swappable by the user. Finally, the TS12’s handguard is rife with M-Lok attachment points for mounting accessories such as a flashlight and a laser-aiming device.

Earthly Tests

Frankly, the TS12 is a shotgun that on paper seems like the most perfect CQB/home-defense arm ever contrived, with its 16 rounds of 12-gauge capacity from a gas-action semi-auto that measures a mere 28 inches in overall length. As such, I waited with the eagerness of Ralphie before Christmas to get my mitts on a production unit.

Yet, I found that paper doesn’t necessarily translate to practicality. There are several design traits that make this shotgun less-than-perfect for combat and/or home defense, including its ergonomics, functionality and, perhaps most significantly, reliability.

Effective Ergonomics

If you’ve ever fired a traditional shotgun with a buttstock that fits you reasonably well (so you can shoot it accurately with little thought while controlling its recoil so it doesn’t pound the demons out of you), then you’ll likely think the TS12 is miserable in comparison. That’s because it is. First off, its stock forms a straight line back from the receiver that is way too high and mandates a high-mounted (AR-15-height) optic. The stock’s polymer comb is much too hard and narrow for comfort—especially when we’re talking 12-gauge rounds that produce anywhere from 20 to 55 ft.-lbs. of free-recoil energy.

It’s actually painful to shoot, and if you were to buy this gun, the first thing I’d recommend would be to stick a thin foam cheek pad on the stock that would promote a firm, yet comfortable, cheek weld. It would do wonders to facilitate speed and accuracy in shooting and to also mitigate pain and headache after extended shooting sessions. I understand why IWI made the stock this way (a recoil-return spring that goes straight back into the stock is simple and it makes the gun look streamlined and futuristic), but it stinks for shotgun shooting.

–

I do, however, admire some of the gun’s controls; its charging handle is well positioned, as is its ambidextrous magazine-unlocking lever that is ingenious in design; its dual loading gates are intuitive and seem to swallow shells just by getting them into the molded cutouts and giving them a shove.

But, there are also negatives to its manual-of-arms. While its large, square safety is positioned well, I do not prefer the position of its ambidextrous bolt-release button that’s found underneath the buttstock. It is simply tough to access with either hand, but I’m hoping it becomes more intuitive with practice. The gun’s Buck Rogers Photon-Blaster-like trigger lands toward the bottom of a huge pile of rotten shotgun triggers, breaking at 9.5 pounds. You can say shotgun triggers don’t matter, but there’s little doubt that lighter ones are easier to shoot well.

Finally, and perhaps most annoyingly, the half-inch gap that forms as the magazine is rotated provides the perfect mousetrap to pinch the shooter’s finger or thumb depending on the direction it is rotated. And when it is pinched, the mag must be reversed to free the ensnared digit. I quickly learned to grip the mag assembly with my palm and first joints of my fingers—not my fingertips—to avoid getting them jammed in this dreaded trap. As such, the TS12 requires practice to operate smoothly. Still, it’s much faster than having to fully reload a traditional shotgun.

Final Thoughts

The Tavor TS12 represents the pinnacle of technological advancement in CQB shotguns at this time, and it’s a marvel of modern engineering. Its ability to fire 16 shells without reloading is impressive, and the 12 gauge’s close-quarters power is unquestioned. This, combined with the fact that it’s less than 30 inches long overall makes it an attractive option for security forces who need maximum firepower carried discreetly, or for units that need a man armed with a shotgun for door breaching. For home defenders, it’s a powerful tool, indeed, as it’s short enough that it can be easily wielded around corners or slung and carried on the back if the hands are needed for other purposes.

In sum, I see the TS12 as a niche shotgun, because as strong as it is in these two areas—mobility and firepower—in other areas it is less strong. To be fair, the TS12 is so new, and I’ve used it so minimally compared with other guns that of course it’s going to seem difficult, just as an AR-15 was alien to me when I first fired it. But, the TS12 is no AR-15; its punishing stock design isn’t conducive to fast or accurate shooting with the significant recoil of a 12 gauge.

Its short-barreled, weight-back design exacerbates muzzle flip, resulting in slower follow-up shots, especially considering the fore-end/rotating-magazine tube hampers vigorous downward grip pressure. The thumb pinch I experienced was enough to make me worry about this pitfall each time I rotated the magazine, which did little for my confidence.

Concerning reliability, the TS12 was not on par with other top-tier 12-gauge semi-automatics. Even after a break-in period of 100 rounds, I experienced about one jam per every 50 shells with heavy loads, and one jam per box with 11/8-ounce target loads. For a defensive/combat arm costing more than $1,300, this is pedestrian performance at best.

In total, I love my TS12 because it gets a ton of oohs and ahhs when my buddies see it in my vault or at the range. Certainly, it looks like the gun of the future, and in theory it is. If you’re looking for a cutting-edge shotgun that mitigates the most difficult element of defensive shotgun use—reloading—then the TS12 is an intriguing new option. If you’re used to more traditional shotgun designs, you’ll have to train with the TS12 a bunch before you’re truly comfortable with it. With new designs come new problems, but also new opportunities.