The five digit number 55-599 became Eli Stern’s sole identity for months as he navigated his way through the most notorious death camps during the Holocaust.

Eli is just one of the thousands of Holocaust survivors that can attest to the brutality of the Nazi regime. Wednesday marks both International Holocaust Remembrance Day and the anniversary of the 76th liberation of the Auschwitz death camp – a camp Eli and his wife Helga Stern know all too well.

Born in Romania in 1930, Eli was the eldest of six children and grew up in Transylvania.

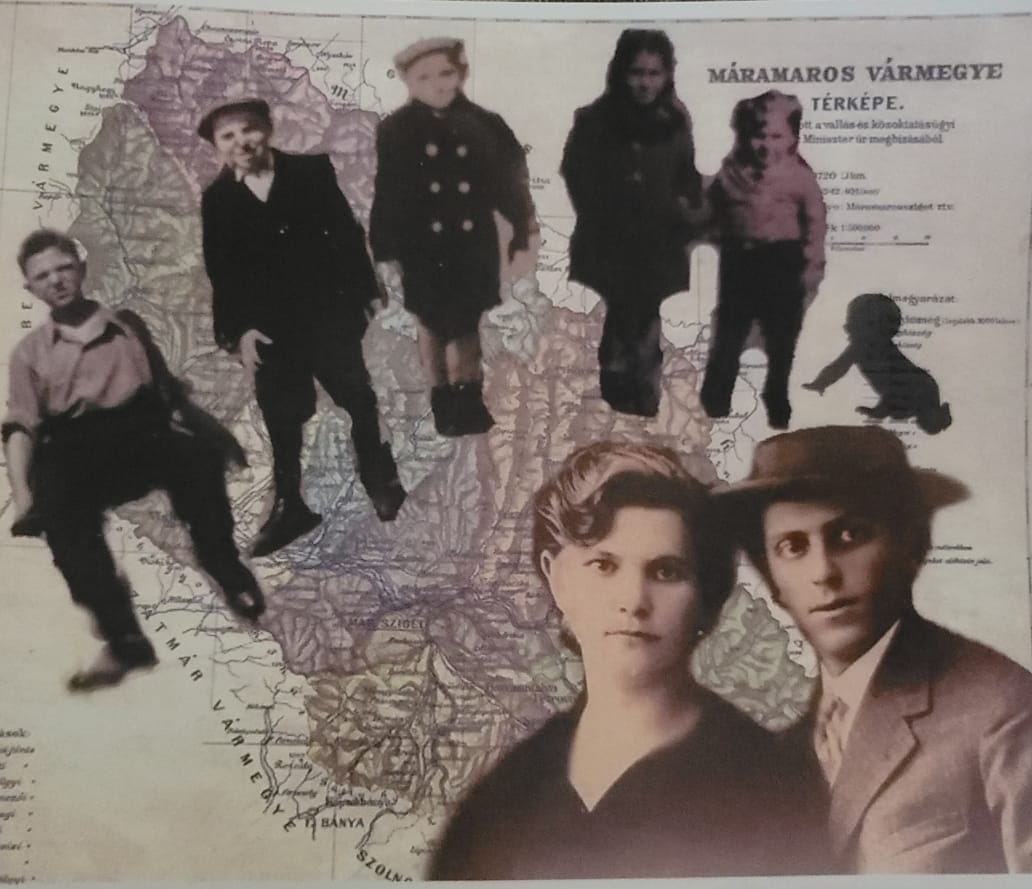

A compilation showing the Stern family. Eli Stern sits to the far left (Photo Credit: Eli Stern)

“There was anti-Semitism, but not as severe as other places had it,” Eli said. “I went to public school. There was name calling but it wasn’t severe.”

Once Hungary began occupying Transylvania, however, things soon changed, according to Eli.

Jews were shuffled into ghettos where they were forced to wear the Star of David to identify themselves and boys as young as 12 were forced to work.

Once the ghetto was filled, armed guards rounded up the Jews and began transporting them to camps.

“We knew absolutely nothing. We didn’t hear about Auschwitz, we didn’t know what Auschwitz even was,” Eli said. “They put us in the ghetto in April of 1944. Within four to six weeks we were sent to Auschwitz.”

Herded into cattle cars and deprived of food and water, Eli said he and his family journeyed to Auschwitz on a near day-long trip, unaware of the fate that awaited them.

They arrived at Auschwitz in the middle of the night “when people were most vulnerable.” In the pitch black, Nazis armed with guns began separating women, children and the elderly from the able-bodied, Eli said.

Eli’s father was sent to work while Eli, his siblings and his mother were told to march.

They were unknowingly headed for the gas chambers. (RELATED: Almost 20% Of New York Millenials Blame Jews For The Holocaust)

Nazis herded the Jews together while Eli clutched his brothers’ hands. They trailed their mother, who cradled the baby.

As the group made their way past barracks filled with sorrowful faces, a Nazi spotted the able-bodied Eli.

As Eli made his way toward a billowing chimney, an SS guard swung the hook of his cane around an unsuspecting Eli’s neck, dragging him out of line as his once tight grip on his brothers’ tiny hands loosened at his side.

“I didn’t realize it then, but I had been saved from the gas chambers. That was the last time I saw my mother and siblings alive.”

OSWIECIM, POLAND – NOVEMBER 15: The door is closed to the crematorium and gas chamber building at the Auschwitz I extermination camp on November 15, 2014 in Oswiecim, Poland. ( Christopher Furlong/Getty Images)

Eli desperately searched for his father, eventually finding him in the midst of a crowd filled with screams of “Daddy” as young boys pined for a familiar face and others began realizing they were alone.

“Why didn’t you stay with your mother? You should’ve stayed with your mother,” Eli’s father said to him.

Desperate for answers, the next morning Eli and other new transports asked fellow prisoners where their family members had been taken.

“They pointed to a chimney and said ‘Do you see that smoke coming out from the chimney? That’s where your families are.'”

Distraught at the realization that their wives, children and other loved ones were sent to the gas chambers, Eli said he watched as distressed men flung themselves against the electric fences, dying by suicide.

After two weeks at Auschwitz, Eli said he and his father were sent to Buchenwald. Eventually, Eli was separated from his father and was sent to another camp, Dora, for a few months before arriving at Bergen-Belsen.

It would take another 7 years before Eli and his father would reunite along the Canadian border.

For the next few months, Eli would endure torturous working conditions, coupled with beatings and lashes if he didn’t follow orders. Forced to sleep on wooden planks and barely given food, Eli would spend nearly a year in the camps until he was liberated on April 15, 1945.

“They put me in a hospital. Have you ever heard of anyone happy to be in the hospital? I was the happiest guy in the world. I had a pillow, I had a sheet, I had a cover and I slept in a bed. I hadn’t done that in years.”

Eli’s wife Helga was born in Germany in 1930, and began experiencing the wave of anti-Semitism that was engulfing the nation by the time she was 8 years old.

Helga Stern as an infant with her family (Photo Credit: Helga Stern)

Following Kristallnacht in 1938, Helga’s parents knew they couldn’t wait much longer to leave Germany, Helga said. Helga was sent to Belgium to live with her grandparents before her parents were eventually smuggled over.

As the war raged on, her parents hired another smuggler to take the family to the free area in France. The smuggler, however, never showed. Unbeknownst to Helga and her family, Nazi guards awaited them as they made a last-ditch effort at securing freedom.

“We started to walk across the border in the middle of the night and we heard shots. We immediately froze and the SS came over. That’s when we knew we were caught. We were with another family and they arrested us all immediately,” she said.

Helga and her parents were taken to a prison in France and within days she was sent to an orphanage-type holding facility for Jewish children while her parents were shipped to Drancy concentration camp, she said.

“My parents were crying,” Helga said. “I don’t think I quite realized the severity of the situation.”

Helga briefly spoke to her parents once more when she received a letter from them informing her they didn’t know what was going to happen or how to get out of the camp.

“I never heard from them again.”

Helga said she escaped certain death on numerous occasions throughout her nearly three-year ordeal, such as when the SS arrested most of the kids at the orphanage she was staying at but didn’t take her or when she was sent to live with her aunt in southern France and SS guards failed to notice she didn’t have a passport when they searched the train she was traveling on.

But by October of 1943, Helga, her aunt and uncle had all been transported to Auschwitz.

“We already knew things were bad, we knew that nothing good could come out of Auschwitz,” Helga said. “We didn’t know what happened to people, one day you saw them and the next day they were gone.”

“One night as I tried to sleep I felt ice cold feet against mine. I knew instantly – she was dead. She was just three years older than I was, and she was dead. It was the worst imaginable thing you could think of,” Helga said.

Like her husband, Helga said she also narrowly escaped the gas chamber after one of the Jewish barrack guards removed her name from a selection list.

Having come down with typhus, Helga said she was certain she would be selected to be sent to the gas chambers.

“The SS guard took my number. I knew in an instant I was doomed. I was crying and the Jewish guard said to me ‘Why are you crying? Be quiet.’ I didn’t realize it at the time, but she saved my life. She took my number off that list.”

The next day, prisoners were marched through the camp naked, Helga said. She said she could hear their wails and screams as hollowed faces searched for a saving grace that never came.

“They all knew where they were going.”

Helga remained in Auschwitz until January of 1945 when the camp was evacuated as liberation neared.

The remaining prisoners who were “healthy” enough to walk were taken on marches through the bitterly cold winter for days on end.

On her first march, Helga walked three days and two nights, trucking through the snow garbed in tattered clothing and rags. SS guards lined the trail of prisoners, prepared to shoot anyone who stopped walking.

“I had a friend who was 14. She was lying in the ditch and had been shot. I kept moving.”

Eventually the prisoners reached a train station where they were packed into tiny cattle cars that had no roof.

As Helga lay on the cold floor packed shoulder to shoulder with prisoners, she noticed a woman standing above her holding a small sack. Desperate, Helga cut a small hole through the sack that was holding just a tiny bit of sugar. A far cry from the one piece of bread given to her just three days earlier, Helga said she squeezed the sugar into her mouth.

“That sugar kept me going, that’s what kept me alive.”

Eventually the group ended up at Ravensbrück and from there were transported to another camp.

Helga was liberated during her final march in April of 1945.

“It was the most beautiful sight in the world to see American soldiers approaching. They were like angels sent down from heaven,” Helga said.

Eli and Helga Stern (Photo Credit: Eli Stern)

After the war, Helga moved to England and eventually immigrated to the U.S. in 1947. She met Eli at a square dance at a Jewish Community Center in Spring Valley, New York, in 1956 and the pair were married in 1958.

However, it would be decades before the couple could begin to recount their horrific experiences. But like Eli, Helga too remembers she was once branded by a five-digit number: 66-495.