President Joe Biden’s $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief plan is an expensive, ambitious attempt to rescue an economy devastated by the coronavirus pandemic. Some, however, worry that the costly stimulus plan could cause hyperinflation.

Hyperinflation, or rapid inflation, occurs when the “prices of all goods and services rise uncontrollably over a defined time period,” according to Corporate Finance Institute (CFI). It’s usually designated hyperinflation when the inflation rate grows at over 50% a month.

This occurs when theres an increase in money supply that is not backed by economic growth, according to CFI.

Biden’s stimulus package includes $1,400 direct payments to individuals earning $75,000 or less or $2,800 to married couples earning $150,000 or less. Parents will receive an additional $1,400 per child. It would also mandate a $15 federal minimum wage. (RELATED: Corporations That Support The $15 Minimum Wage Can Afford It. Here’s Who Can’t)

The president’s proposal is three times as large as the $618 billion package put forward by his Republican counterparts. Along with the minimum wage mandate and the direct payments, Biden’s plan includes an eviction moratorium through September of 2021; $400 billion for vaccines, testing, and reopening schools; employment benefits; $90 billion to businesses and communities; and $350 billion in emergency funding to state and local governments.

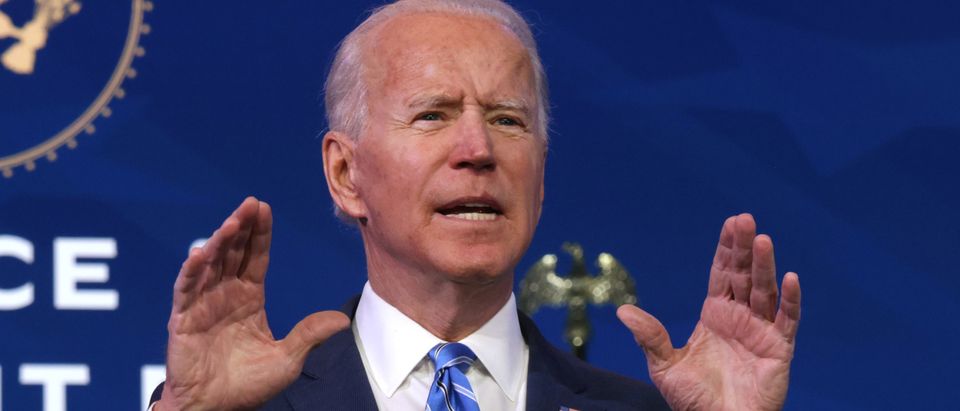

U.S. President Joe Biden (Center R) and Vice President Kamala Harris (Center L) meet with 10 Republican senators, including Mitt Romney (R-UT), Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Susan Collins (R-ME), in the Oval Office at the White House February 01, 2021 in Washington, DC. The senators requested a meeting with Biden to propose a scaled-back $618 billion stimulus plan in response to the $1.9 trillion coronavirus relief package Biden is currently pushing in Congress. (Photo by Doug Mills-Pool/Getty Images)

Several Democrats have expressed concerns about Biden’s stimulus package. Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders said on ABC’s This Week that he has “differences and concerns” about the bill, but that he believed it needed to pass in order to help American families. Sanders did not specify what his concerns were.

CNN Analyst Rachael Bade said in late January that some Democrats were “rolling their eyes privately” when Biden talked about bipartisanship.

“Clearly there is a divide here,” Bade said. “I mean, the interesting thing, I think, to watch will be it’s not just Republicans who have expressed concern about this $2 trillion package. Over the weekend there were a couple of Democrats who also expressed concern with the price tag.” (RELATED: Americans Want Stimulus Checks — Will Republicans Get On Board?)

A bipartisan group of 16 Senators pushed back against certain parts of the bill during a January phone call with White House officials, according to a Politico report. Maine Independent Sen. Angus King expressed concern about the price of the package, saying that “this isn’t monopoly money.” Some Senators on the call, including Republican Maine Sen. Susan Collins, questioned why the stimulus payments were not more targeted towards those in the greatest need.

“I was the first to raise that issue, but there seemed to be a lot of agreement … that those payments need to be more targeted,” Collins said according to the report. “I would say that it was not clear to me how the administration came up with its $1.9 trillion figure for the package.”

It’s true that the bold proposal could have far-reaching consequences for the economy. Hyperinflation could reach levels “of a kind we have not seen in a generation,” Washington Post columnist Lawrence Summers wrote. If monetary and fiscal policy were adjusted quickly to address the problem of inflation, it could be handled – but the administration has been dismissive of even the possibility of inflation and Congress has been hard-pressed to support either tax increases or spending cuts.

The stimulus proposal would essentially commit 15% of GDP to address the problems of economic injustice, slow growth, and inadequate public investment in things like infrastructure, education, and renewable energy, according to Summers. The problem, however, is that Congress will be committing 15% of GDP with no increase in public investment aimed at tackling those issues – leaving a post-pandemic world without “political and economic space” to address these challenges.

As the final details of Biden’s stimulus package are created, “it will be essential to carefully consider how the choices we make now may constrain what we are able to achieve in the future,” Summers said. “The Biden plan is a vital step forward, but we must make sure that it is enacted in a way that neither threatens future inflation and financial stability nor our ability to build back better through public investment.”

The last time the country was on the verge of hyperinflation, it was dealt with by Ronald Reagan, who has been credited with saving the economy from the brink of disaster. Washington Post op-ed columnist Robert J. Samuelson wrote in 2011 that Reagan’s “defeat of double-digit inflation” was his “singular domestic achievement and the wellspring of his popularity.”

Between 1979 and 1984, inflation had fallen from an average of 14% to around 4%, according to the Washington Post. Along with Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volcker, Reagan was able to crush hyperinflation and restore confidence in the American economy through his policies known as Reaganomics.

Reaganomics is an economic theory that tax cuts grow the economy by putting more money in the pockets of consumers, which they go and spend. Reaganomics is based on supply-side economics, sometimes called trickle-down economics, which says that corporate tax cuts grow the economy by allowing companies to keep more cash and grow their businesses, eventually hiring more workers and creating jobs. Income tax cuts also increase the supply of labor by giving workers more incentive to work, according to the theory.