By Mark Keffe, American Rifleman

Modern Ruger semi-automatic pistols, and to that group I shall include the just-introduced MAX-9, don’t quite fall into the late Rodney Dangerfield’s “I don’t get no respect” category, but I think it is fair to say that they do not receive the full faith and credit they deserve.

While Ruger has its fans, and I count myself among them along with the NRA-affiliated Ruger Collectors Ass’n, the company’s pistols don’t have legions of “fan boys” eagerly willing to gobble up and gush over even the most minor variation with gusto. No, Ruger semi-automatic pistols, all made in the USA, of course, actually need to compete on the basis of features and price. Often when Ruger enters a category, its actual price will be lower than that of competitive designs, and that is based typically upon volume and manufacturing efficiency. In case you were wondering, that efficiency also occurs as Ruger’s engineers are designing the guns to be manufactured. When you make a lot of things very well—which might as well be plastered above the door on your way into a Ruger factory—you can afford to keep the price competitive.

Such is the case with the new MAX-9, which delivers the en vogue increased capacity of a 10- or 12-round magazine in a gun that is still small and light enough to be carried in a pocket—albeit a man-size pocket.

For Ruger, it appears that nothing is as easy as it seems. The intent with the MAX-9 was to simply take the top of the affordable and proven LC9 and mate it with a slightly wider grip frame that accepts a double-to-single-column magazine rather than the LC9’s seven-round, single-stack box. In the end, though, Ruger engineers tinkered with and upgraded the parts and features, and ended up with a pistol with surprisingly few, if any, interchangeable parts to its parent. It may not be a completely new design, but the parts for it sure are.

–

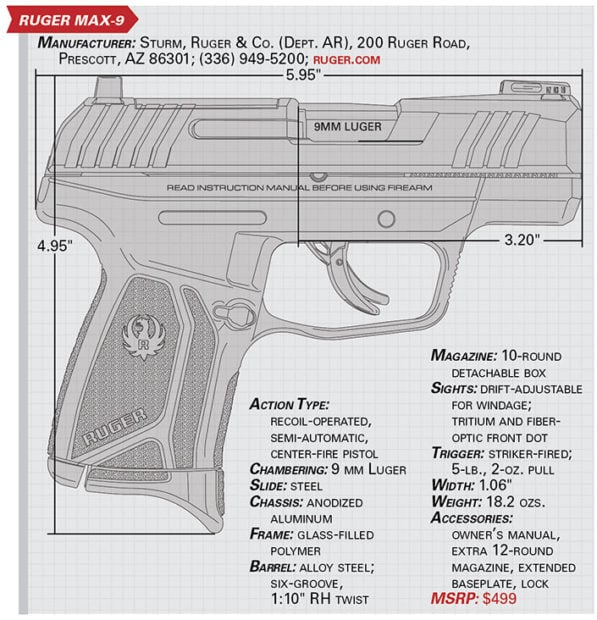

This is a recoil-operated, striker-fired, 9 mm Luger pistol that measures 5.95″ long and either 4.69″ or 4.95″ tall, depending on which magazine is in the gun, which we will get to in a moment. The grip area of the black, glass-filled-nylon frame is 0.955″ wide and 1.91″ front to rear. But there are some very subtle ergonomic touches to it. The beavertail at the frame’s rear sits pretty high, allowing the shooter to get the web of the hand well into the gun. On each side there are slight thumb rests that taper from 0.955″ to 0.893″. There are also panels of stippling on either side—into which the Ruger name and logo are molded—and the stippling isn’t terribly aggressive. Panels are also on the frontstrap and backstrap. The trigger guard is undercut at its base to allow the middle finger to ride just a little higher on the frame.

In terms of width, the gun measures 1.04″ at the safety (because the Pro model lacks a manual safety it is a bit narrower), 0.94″ at the slide and 1.06″ at the widest point of the frame (the magazine release). All controls are on the left side of the frame.

The MAX-9 includes a slide lock between the takedown pin and safety, and the gun locks back on an empty magazine. There is a fence molded into the frame around the slide lock to prevent activating it inadvertently. The magazine release is on the frame’s left near the junction of the trigger guard. Its face is vertically grooved and easy to reach, and it is reversible for southpaws. The trigger guard’s front bears horizontal serrations.

The frame contains the double-column, single-feed magazines, which are 0.80″ at their widest, tapering down to 0.58″ at the top. The taper is fairly gentle during that double-to-single transition, and the magazines did not prove to be difficult to load, especially with my handy Maglula.

The slide is of black-oxide-treated carbon steel and has a matte finish. There are shallow forward and rear chevron-shaped slide serrations on each side, and the slide’s front, top and sides are scalloped to make holstering the gun easier.

The gun comes with two Teflon-coated magazines, a flush-fitting 10-rounder and an extended 12-rounder. You can choose whether to have a slight finger extension on the 10, which gets all four fingers onto the gun, or go with the flush version to maximize concealment.

The MAX-9’s striker is fully cocked as the slide is manipulated. It uses the rotary sear design previously employed by Ruger. Pulling the trigger begins with depressing the articulated blade safety on its front face; once it’s out of the way, trigger movement can begin. From there, the trigger acts on the trigger bar, which moves the sear downward while also pressing upward on the passive striker safety in the slide’s underside, which allows the striker to travel forward to hit the primer of a chambered cartridge. The trigger pull measured 5 lbs., 12 ozs., and there is no second-strike capability. There is a rather long take-up in depressing the trigger’s safety, followed by a short, solid but somewhat spongy pull, then the reset itself is short and positive.

WATCH:

The 3.20″-long barrel operates in the well-proven tilting method, with its hood locking into the slide’s ejection port. At the muzzle, there is no bushing but rather a bell shape that aligns concentrically within the slide’s front. Rifling is six-groove with a 1:10″ right-handed twist. The barrel is an upgrade over the standard LC9 in that it is hammer-forged, and there is a slight cut in its top to allow visual inspection of whether a cartridge is chambered or not. The external extractor is on the slide’s right, while the fixed ejector is on the frame’s left.

Unloaded weight is 18.2 ozs. with the 10-round magazine and no optic with the steel cover plate in place, while a Shield RMS-equipped gun with the 12-round magazine topped out at just shy of 19 ozs. unloaded.

There is a 0.5″-long grooved safety lever at the top rear of the frame that pivots at its rear. Pressing it down to the fire position reveals a red dot, while pressing it upward to the “on” position blocks the striker and slide.

–

The operating parts are contained in a non-removable aluminum chassis to which all the fire-control components are attached. There is a trigger bar inside the right that connects the trigger to the sear and the passive firing pin safety. In order for the sear to release the striker, the passive firing pin safety needs to be moved out of the way by its connector.

There is no doubt that the optics-ready movement is in full-swing. Whether or not one actually mounts a micro red-dot, making the pistol capable of accepting one is something that is far easier done at the factory on CNC machines than by a gunsmith afterward. All MAX-9 pistols come optics-ready with the cover plate on the top of the slide secured by two Torx screws. The footprint is of the JPoint pattern, and I mounted both a Shield RMS and the new Hex Wasp from Springfield Armory onto the pistol for testing.

The sights received particular attention from Ruger’s engineers. The front sight dovetail has the same dimensions as those of the Smith & Wesson Shield, and the rear dovetail matches that of the S&W C.O.R.E, which means aftermarket sights that fit the MAX-9 are already available.

The rear is a notch with a black outline, but its front face is flat so it can be used to rack the slide against another surface if one-handed operation becomes necessary. What Ruger did was concentrate on the front sight, and what the pistol uses there is a Hi-Viz green fiber-optic that has a tritium circle as well. This makes it a good sight for daylight use, but you can also find that tritium circle in the dark.

Takedown is a little unconventional, as there’s no traditional disassembly lever, but it will be familiar to the legions of LC9 owners out there. With a magazine removed, and after checking to ensure the pistol is unloaded, allow the slide to go fully forward and then pull the trigger. On the left side of frame, ahead of the slide lock, is the grooved takedown plate. You should be able to push it down with your finger. This allows access to the takedown pin. Retract the slide about 1/8″ and, using a punch, push the pin out from right to left. Once it is removed, the slide can be taken off of the frame. This will allow you to get to the underside of the slide and remove the recoil spring assembly, which has two springs—one coiled at the rear and one with a separate guide that is flat.

The one potential knock on the MAX-9 is the trigger reach length, which is 3¼” from the web of the hand to the tip of the blade safety in the trigger blade. That said, there is sufficient room inside the somewhat-elongated trigger guard even for those whose fingers dwarf bun-size Ball Park franks.

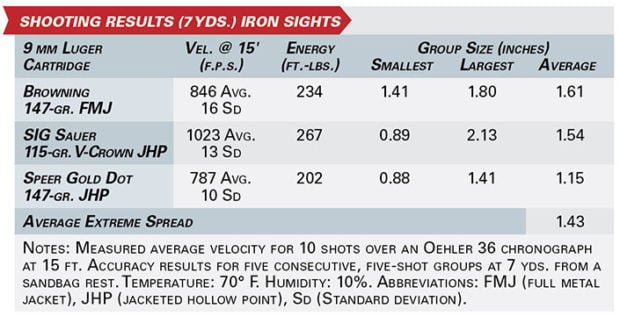

The MAX-9 was fired for accuracy at 7 yds. with the iron sights and function fired with a Shield RMS mounted, and the results can be found in the accompanying table. Throughout the course of about 840 rounds fired from two guns—one with the optic and the other with the supplied metallic sights—there were no malfunctions of any kind. Four different magazines were used with an assortment of ammunition from Aguila, Colt, Federal, Remington, SIG Sauer and Winchester, with bullet weights ranging from 115 to 147 grs. The MAX-9s gobbled through even mixed magazines of ammunition left over from other tests with aplomb.

While you can’t get away from the physics of shooting a small 9 mm pistol that weighs little more than a pound, the perceived recoil from multiple shooters was regarded as not unpleasant. That cannot be said about all of the guns in this category. Our colleagues at NRA Women thought highly of the MAX-9, deeming it easy to operate, and they, too, found the perceived recoil to be less sharp than anticipated.

High marks are given to the interface between the frame and the web of the shooter’s hand, as they are completely smooth with no irritating edges. As compared to some other guns in this category, it seemed the slide velocity was not as pronounced, resulting in a less sharp impact as it bottomed out. I believe the dual-recoil-spring design, as well as the radii at the back of the frame, contributed to the overall shootability of the MAX-9.

Remember the efficiencies I mentioned earlier? The price for the MAX-9 is about $100 below its closest competitor at the time of this writing. While an attractive price tag certainly helps, the optics-ready Ruger MAX-9, with its excellent sights, good trigger and pure shootability, can stand on its own.