With gas and food prices surging (along with seemingly every other price), Americans are suddenly talking about the so-called “Misery Index.” Americans who lived through the Jimmy Carter years will likely recall the Misery Index: it’s the sum of America’s inflation and unemployment rates. As the name suggests, higher is bad. But only so much.

Consumers and economists alike were shocked by last month’s 4.2 percent inflation rate. It was the fastest year-over-year inflation rate since September 2008. Combined with April’s 6.1 percent unemployment rate, America’s Misery Index stood at 10.3 percent last month — more than double the pre-pandemic rate.

Granted, the current Misery Rate is elevated. But is that meaningful? Or is the Misery Index simply a convenient Republican political talking point?

Prior to the pandemic, the United States enjoyed a historic era of low inflation and unemployment. It took a global pandemic to devastate those idyllic economic conditions.

Yes, the pandemic upended everything.

The first question one must ask is if this spate of inflation is transitory or, alternatively, the start of a painful return to an inflationary era. That’s uncertain. But most would agree the downside risk points to higher inflation.

Regardless, the Misery Index doesn’t reflect a country’s underlying economic strength. A country’s Misery Index doesn’t matter per se. What matters is a country’s potential per capita productivity.

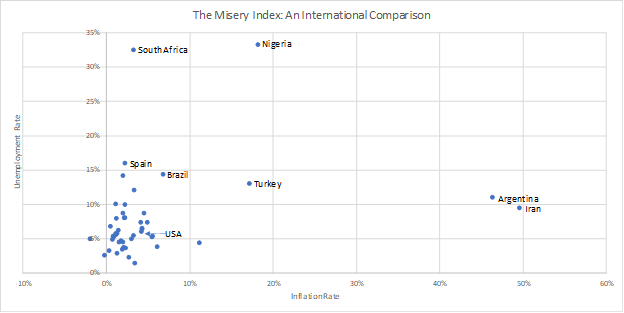

Differences of measurement aside, the United States’ Misery Index ranks 23rd out of the 48 countries for which real-time data is readily available. At first glance, that’s awful.

But consider the data:

- The worst Misery Index, coming in at just over 3,000 percent — driven largely by rampant inflation — is held by Venezuela.

- Iran, Argentina, Nigeria all exhibit Misery Indices exceeding 50%, followed by South Africa and Turkey with indices of 30% or more.

- From there, the Misery Index drops off from the disastrous to the merely undesirable: Brazil, Spain, Colombia, Pakistan, and Chile are all saddled with Misery Indices exceeding 15%.

Graph courtesy of Jim Carter

As painful as the U.S. Misery Index appears to be at 10.3%, it is relative benign. America is hurting, but a considerable slice of the world — totaling more than 1 billion people — is in anguish.

First, realize the Misery Index is a snapshot of a given period. One or two months of inflation do not make an era. (Regardless, we don’t give Venezuela much hope.)

Second, the Misery Index does not reflect a country’s underlying economic strength or direction. The U.S. Misery Index stood at 10.3% last month. Vietnam’s Misery Index was 5.1 percent. Would anyone in their right mind trade places? We think not. America’s per capita GDP is roughly 20 times that of Vietnam.

Finally, U.S. GDP grew at an annual rate of 6.4 percent in Q1 — one of the globe’s fastest growth rates. And now the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta estimates the U.S. economy will grow at a red-hot 10.5% annual rate this quarter. The Misery Index aside, the U.S. economy is emerging from this pandemic-induced downturn far better than most countries.

So where does the U.S. economy go from here?

What matters is the current and future direction of U.S. economic policy. We must ask ourselves, does the Biden administration’s policies:

- draw more people into the labor force or keep them on the sidelines?

- provide or deny workforce training to enhance American productivity?

- incentivize or block employers from providing their employees with productivity-enhancing equipment and tools?

- reduce or increase costly regulatory barriers?

- promote or stunt the adoption of new, productive technologies?

- throw trillions of dollars at programs that do little to enhance America’s competitive edge?

Despite the political intrigue, one thing is clear: Achieving and sustaining rapid economic growth will require the U.S. to field a larger, more productive labor force. The U.S. government can help make that possible.

Now let’s get to work.

James Carter served as a Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Treasury and Deputy Undersecretary of Labor under President George W. Bush. Mary Crescent Carter is a senior economics major at Tulane University and a former White House intern (2020).