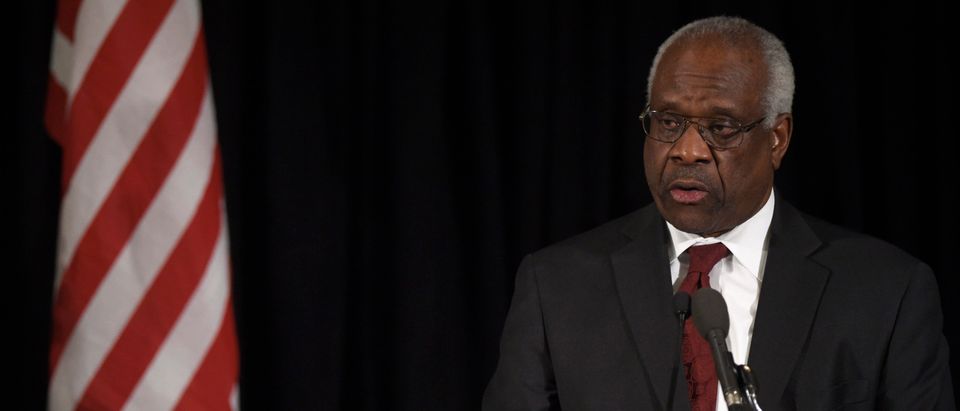

Editor’s note: What follows is an excerpt from Michael Pack and Mark Paoletta’s book “Created Equal: Clarence Thomas In His Own Words.” It can be purchased here.

Michael Pack: The big driver for the Democrats opposing you was Roe v. Wade. They asked lots about that, and in many ways.

Clarence Thomas: I think it was central to a lot. It was certainly the key to the opposition from many of the women’s groups. I just thought it was ironic that in my whole life, through all the years of preparation, and coming through Georgia, and all the challenges, that of all the things that they’ve reduced it to was something that wasn’t even an issue in your life. Wasn’t a matter you’ve thought about, but because that issue is so important to them, they will wash over your entire life. They will vandalize the little life that you’ve cobbled together because their stuff is so important.

What I realized, and should have realized more fully, is that you really didn’t matter and your life didn’t matter. What mattered was what they wanted, and what they wanted was this particular issue. And regardless of what I had done with my life, where I had been, where I had lived, it was all cancelled out, unless I agreed two plus two equals five. You have to say it. And that makes it true. Because they want it to be true.

MP: The Democrats spent a lot of time trying to get you to commit on how you would rule on abortion, and you did not want to commit.

CT: One, I didn’t know. And two, I had just read all those cases again. I hadn’t read those cases about privacy, and I hadn’t thought much about substantive due process since law school. I had constitutional law in 1972; Roe was decided in 1973. I was more interested in the race issues. I was more interested in getting out of law school. I was more interested in passing the bar exam. My life was consumed by survival. I couldn’t pay my rent. I couldn’t repay my student loans. I had all these other things going on, that you were navigating, these worlds you’re navigating.

They think we all should have been concerned about this one issue. I hadn’t really thought about it. I thought about it generally but not in the sense that I had read Roe or re-read Griswold. This wasn’t my issue. I have no idea why they thought it should be my issue, why I should think about it in the way they did.

MP: They refused to believe that you had not discussed it.

CT: Well, you know what? They refused to believe a lot of things. Isn’t that fascinating? I had to have discussed it because they wanted me to discuss it. It goes back to their thinking on affirmative action. You have to believe in affirmative action because we think you ought to believe in affirmative action. Well, how is it different from slavery? How is that different from segregation? How is that different from being told, “You can’t walk across that park”? “Oh, you can’t think those thoughts.” “Oh, you could not have done that.” “You could not have used your time that way.” How is that any different? You know what? I’d prefer to be excluded from the park because I can live my life quite freely without having set foot in a park. But you can’t live it freely without having your own thoughts. The idea that, “I have to do this,” I found that more repulsive than the specific thing about which they thought I should think.

MP: Now, they might not have liked your views about affirmative action, but they knew them. In the Roe case, they thought they knew what you thought, even though you hadn’t said it.

CT: They must have been in séances, or something, or are into reading chicken feet or something like that, because I had not discussed it. How would they know when my wife didn’t know? How would they know when I didn’t know? If I asked them a question: “What is your view on the new advances in quantum physics?” And you say, “I don’t know.” I could say, “I refuse to believe you don’t know, I refuse to believe you hadn’t thought about it because that’s all I’ve been thinking about for the past five years.” I make light of it, but the point is, not everybody thinks about what you think about. Not everybody reads the same books. I read the things I’m interested in. I’m interested in diesel motors and the difference between an 8v92 and a Series 60 Detroit Diesel. How many people are interested in that? Maybe two? That’s all I’m interested in, and you should be interested in this. That’s absurd.

The abortion issue is a much bigger issue, obviously, but the point is, I hadn’t thought about it. I thought about it in the sense that maybe it would be hard—but constitutionally, ever read the cases? No. I was more in the race issues. I was more interested in black kids getting an education. I was more interested in the breakdown of the family. I was more interested in the social pathologies that were coming the way of blacks. Look at what I read, look at what I was interested in. Did Richard Wright or Ralph Ellison or Harper Lee have some long Supreme Court Nomination exposition or long discussion on abortion? No, that isn’t what we were talking about. You’re talking about race because that was a central part of our lives.

MP: They didn’t want Roe to be overturned. And that was, as you say, the one thing that trumped everything else.

CT: Well, perhaps they wanted assurances, which is precisely what a judge shouldn’t be doing.

MP: And one of the themes of the confirmation was how should judges decide, and what would your role be as a judge.

CT: I don’t think they believe that a judge is to be impartial. I think they believe in legal realism. I think some people don’t believe that law is to be neutral. They think that you bring a bias, and it’s reflected in the way you judge.

MP: They didn’t believe perhaps that you could judge impartially without simply going with your bias.

CT: Maybe that’s because that’s what they would do. There’s a lot of projection here. They project their views on you, they project their attitudes, their outlook, the way they would do things on you. Well, that’s not me. I’ve heard them say to me, “Well, if that happened to me, this is what I would have done.” So that’s what you would have done. Or they say, “Oh everybody does it.” So you spread a certain approach or you make it universal.

MP: Right after the hearings, were there also written questions you had to respond to?

CT: We actually spent a lot of time responding to written questions. And it never ended because you had more people challenging what you said. Then the propaganda starts, that, “Oh you lied.” They love to call you a liar. That’s the first thing they love to say, “Well, you say you didn’t discuss Roe. Everybody discussed Roe. You’re lying.” So then the propaganda starts on that. Then they continued raising more questions, asking more questions. And then you had all the people who were testifying against you. I love people who show up and testify against you, whom you’ve never met. When you’re nominated, you have people who show up that you barely know, who become experts on you, and these people testify against you, you don’t know them from a hill of beans. And people say all sorts of things. You become this piñata, and you start attracting everybody who wants attention.

Michael Pack is the former CEO of the U.S. Agency for Global Media and director of the 2020 documentary film, Created Equal: Clarence Thomas In His Own Words.

Mark Paoletta served as an attorney in the George H. W. Bush White House and worked on Justice Thomas’ Supreme Court confirmation.