America celebrated the Constitution’s 235th anniversary on Sep 17. Today, Americans still live under the oldest surviving written constitution on Earth, a document whose restraints on arbitrary power still (in theory — see Biden’s recent student loan forgiveness) leave the government just enough power to pass and execute necessary laws. Today, it is maligned as the product of cis-gendered white men, mangled by executive overreach and loose interpretation, and mocked in the academia as irrelevant folk wisdom at best. Nevertheless, the Constitution, and particularly freedoms specified in the Bill of Rights, are etched in most Americans’ political DNA. Many of our most potent “culture-war” issues focus directly on constitutional interpretation, from religious freedom laws, censorship of certain speech, gun rights and gun control, and the surveillance state.

The Constitution operates as a system of checks and balances to “connect and blend” the duties of the several branches so that none can legislate, execute, and judge by itself (the “very definition of tyranny,” according to James Madison), a sort of machine which balance the ambitions of different interests to control popular passion and politicians’ greed alike. But the Constitution also operates on a much deeper, moral level. While the Constitution’s checks and balances make the government work, its moral underpinning endears the American public to the Constitution’s guarantees of a “republican form of government.”

The Constitution was not an attempt to create a utopian moral system out of nothing, as in the chaotic and bloody French and Russian revolutions. It was created to protect the ideals of the Declaration of Independence, that “all men are endowed by their Creator,” and that legitimate governments derive their “just powers from the consent of the governed.” A legitimate government must protect the rights of its citizens against three major dangers: external attack, deprivation of liberty or property from another citizen (commonly called “crime”), and government itself.

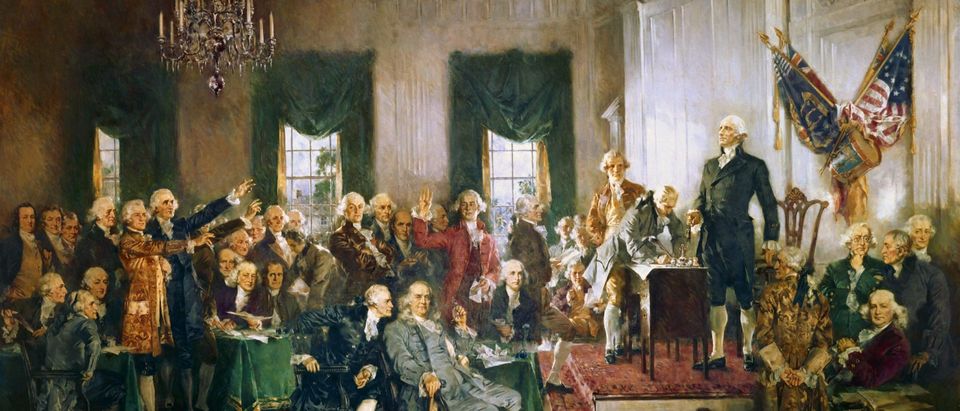

For that purpose, the Constitution—a “picture [frame] of silver” — was framed to put into practice the ideals of the Declaration — the “apple of gold” — as President Abraham Lincoln said, referencing Proverbs 25:11. In Lincoln’s quote, and in the debates of the Constitutional Convention and the writings of its most prominent framers, we see that the Constitution is not just a legal system. It was framed “for a moral and religious people … wholly inadequate to the government of any other,” as John Adams stated. It arose in the context of a Judeo-Christian worldview that treated individual human beings as God’s divine creations, not the useless underlings of the higher-born such as nobles and kings.

Yet, Americans today, including many conservatives, such as Derek Hunter in a recent Townhall article, separate constitutional and moral questions, leaving the interpretation and application of the Constitution to unelected judges and Ivy League lawyers. “We’re not dealing with morality; we’re dealing with the Constitution,” Hunter states in opposition to Lindsey Graham’s 15-week abortion ban. This is nonsense.

From where do the rights to free speech and free religion contained in the First Amendment come from? These rights arose from the idea that individual human beings are created by God with equal worth before God. The same could be said of the Thirteenth Amendment banning slavery, or of the Fifth Amendment’s rights to due process. These all arose from a sense of moral obligation to recognize the worth of all American citizens before their Creator, not from a political laboratory experiment. Thus, separating the constitution from its religious underpinnings is foolish and self-defeating.

Every clause of the Constitution, every proposed amendment, was either accepted or rejected based on the moral and practical sense of the American people. American republicanism, embodied in the Declaration of Independence and Constitution, arose from convictions of right (natural rights and government by consent of the governed) and wrong (despotism and the denial of those rights), or “morality.”

Whether our national morality favors extending protection to the unborn as we have previously extended protection to other classes of citizens whose rights were not fully recognized in 1787 is a legitimate debate. But it is ridiculous to claim that the supreme, fundamental law of the land is amoral. Generations of Americans gave their lives, fortunes, and sacred honor for it on battlefields from Yorktown to Shiloh and Okinawa. The Constitution is still the “glorious liberty document” that anti-slavery crusader Frederick Douglass read in the 1850s. To assert anything less is to slander the Founders, who hoped that the American example would further human liberty everywhere and that its Constitution would make our government an example to emulate.

Nathan Richendollar is a summa cum laude economics and politics graduate of Washington and Lee University in Lexington, VA. He lives in Southwest Missouri with his wife Bethany and works in the financial sector.

The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the Daily Caller.