Cassandra, the Trojan priestess of Apollo in Greek mythology, had it easy. She was cursed to prophesize the truth, but never to be believed. At least she didn’t have to report her prophecies to the U.S. Congress.

The Congressional Budget Office isn’t so lucky. On March 4, CBO updated its long-term budget outlook, repeating a warning that has grown all-too-familiar: unrestrained deficit-spending poses “significant risks” and could lead to a potential “fiscal crisis” accompanied by “higher inflation” and “an erosion of confidence in the U.S. dollar.”

As dire as CBO’s warnings are, is anyone listening? Exactly one week after CBO issued its report, President Biden signed a $1.9 trillion piece of legislation into law, further ballooning the federal debt. And now policymakers are crafting an infrastructure package — perhaps totaling as much as $4 trillion — with little idea of how to pay for it.

Before we add trillions more to the debt, just how bad is the country’s long-term fiscal outlook anyway? To borrow a line from former New Jersey Governor Richard Codey: “The good news is, we’re not bankrupt. The bad news is, we’re close.”

A Little History

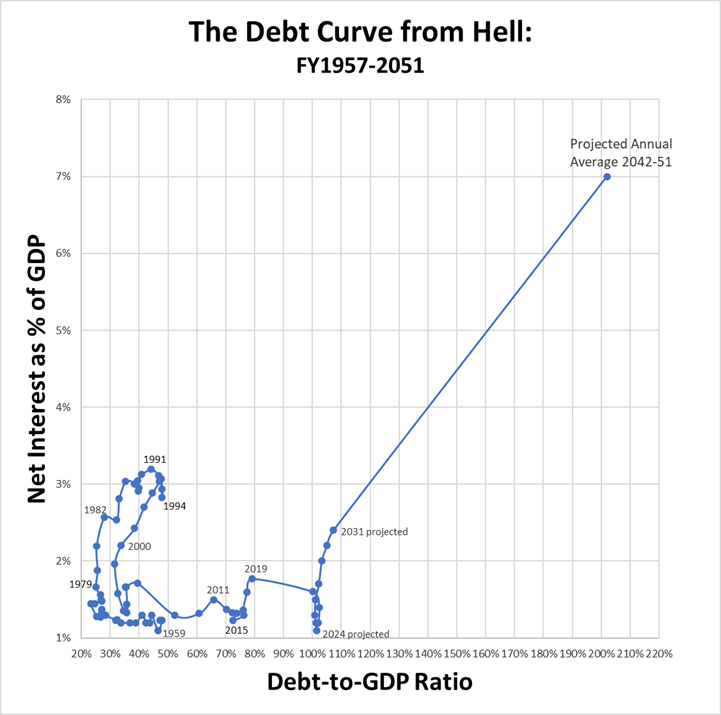

For more than fifty years, from 1957 to 2008, the publicly-held federal debt never exceeded 47.9 percent of gross domestic product. Analysts projected a large and sustained increase in the debt relative to GDP, but lawmakers were comforted by the knowledge that the day of reckoning wouldn’t occur for years.

Then came the Great Recession. The recession brutalized the economy and, with years of debt compressed into mere months, the publicly-held federal debt rose to a level not seen since the late 1940’s.

Then came the pandemic. Measures to keep the economy afloat ballooned the federal debt by trillions of dollars virtually overnight. By the end of this year, the publicly-held debt is projected to total 102% of GDP.

Source: Congressional Budget Office, 2021

Source: Congressional Budget Office, 2021

One saving grace of the Great Recession — and also of the pandemic — was the run-up in the federal debt occurred as interest rates collapsed. This allowed the federal government to finance its debt at little cost.

As recently as fiscal year 2016, the federal government spent $240 billion on interest on the federal debt. That’s $1 billion less than the federal government spent twenty years earlier to carry a debt roughly one-fourth as large.

The Situation Today

Federal interest costs jumped 56% over the three years ending in fiscal year 2019 as interest rates started to normalize. But with the pandemic and the renewed collapse in interest rates, net interest costs are projected to fall this year and for each of the next three years … before nearly tripling over the following eight years to approximately $800 billion annually.

Rising interest costs will consume an increasingly larger share of all new federal revenue. This will place severe pressure on the federal budget.

By the decade of the 2040s, net interest is expected to cost the federal government the equivalent of seven percent of GDP — up from between one to three percent over the fifty years leading up to the Great Recession.

Factor in the projected increase in federal outlays for health care and other mandatory programs, and the federal budget gradually spirals out-of-control. Deficits grow the debt, and that growth aggravates the deficit. It’s a vicious cycle.

Consequently, avoiding fiscal catastrophe will require policymakers to stabilize (and, ideally reduce) the federal debt-to-GDP ratio through deficit reduction and policies to accelerate long-term economic growth.

Unless taxpayers are willing to shoulder a substantially larger tax burden, most of the deficit reduction must come from restraining mandatory spending growth. Discretionary outlays are already projected to shrink significantly as a share of GDP while mandatory spending (excluding COVID-related programs) is poised to grow considerably.

Spending restraint and deficit reduction will produce additional savings in the form of smaller interest payments, further reducing the deficit. A virtuous cycle!

Faster economic growth is the other key to avoiding fiscal disaster. Ultimately, this will require new policies to encourage labor force participation, to hasten technological progress and to enhance productivity by better training and equipping our workforce.

We know what must be done. Let’s hope U.S. policymakers pay more attention to CBO’s warnings than the citizens of Troy paid to Cassandra. As legend has it, Cassandra warned the Trojan Horse would lead to Troy’s downfall. She was right.

James Carter served on the staff of the U.S. Senate Budget Committee. Previously, he was a Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Treasury and Deputy Undersecretary of Labor under President George W. Bush.