- There is strong evidence that the Census Bureau’s population growth projections are wildly optimistic.

- Population forecasting is extremely important for predicting the solvency of entitlement programs and government services, so it must be accurate.

- To get more accurate forecasting, the Census Bureau would need to invest in better methods and researchers.

The most recent report of the Social Security trustees suggested that the trust fund reserves will be depleted in 2034. This is a dire warning. The only problem is that it’s wrong: It’s far too optimistic.

The same story goes for the Congressional Budget Office’s long-run budget projections. They say that debt-to-GDP will rise to 144% by 2050. That’s bad. But it’s not bad enough to accurately reflect reality.

Indeed, virtually every forecasting body in America, from Goldman Sachs to the Social Security Trustees, is wrong. Painfully wrong. Those whose job is to anticipate the future are engaged in a colossal project of collective negligence.

The wrongness runs deep. For example, Goldman Sachs’ most recent public research on demographic change suggests that “rising life expectancies” will have little economic effect on America. The only problem? Life expectancy in America is falling. It was falling in June 2018 when Goldman’s researchers published their poo-pooing of the role of demography in driving economic changes.

Private forecasters can perhaps be forgiven for negligence: Those who suffer from their inadequate research are shareholders who chose to invest in those firms (well, mostly).

But when widely trusted public bodies fail to do their duty to the public and provide the best possible forecasts, the general public is justified in being a bit irritated. We are justified in wanting our policymakers, our budget planners, the people who are responsible for the public fisc, to be responsible. An essential part of responsibility is making sure your planning information is up-to-date.

Why are all these forecasts so wrong? We can confidently point to their errors because their mistakes don’t come from inherently hard-to-predict, fast-changing factors like the business cycle or financial crises, but a relatively slow-moving and predictable factor: population. For a detailed example of this demographic forecasting error, it may help to see it manifested in America’s premier population research center: the Census Bureau. (RELATED: The Supreme Court Just Ruled On The Census Citizenship Question)

The Census Bureau’s current projections say that there will be 404 million Americans in 2060. Those projections are wrong.

The Census Bureau produces periodic projections of population for the United States. These projections are produced by trained demographers using the best available methods. The most recent forecast is the 2017 National Population Projection. Now, “2017” is an odd label here: they were published in 2018, but they reflected data inputs through 2016.

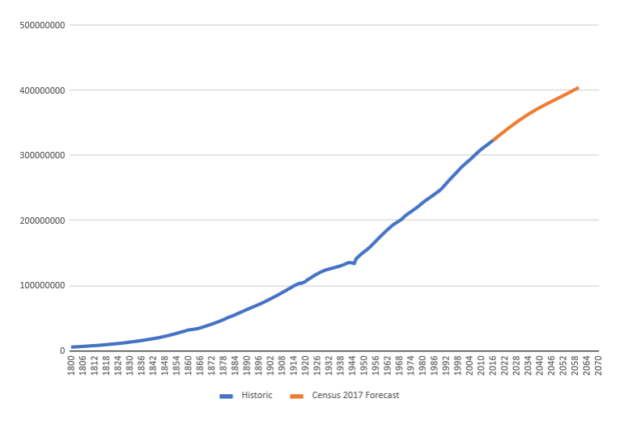

That projection yields the following expectation of population:

FIG 1: Long Run and Projected Population

That makes it look like the population future for America is “business as usual:” growth continues unabated!

But is that projection reasonable? Well, the last “input data” was for 2016. We now have newer Census estimates for birth, death, and migration data for 2017 and 2018. Estimates refer to experts’ best guess, from available data, of past population change, while projections refer to experts’ best guess, from available data, of future population change. So by comparing recent estimates for a given year to the projections that were provided for those years, we can make a reasonable assessment of the accuracy of those projections.

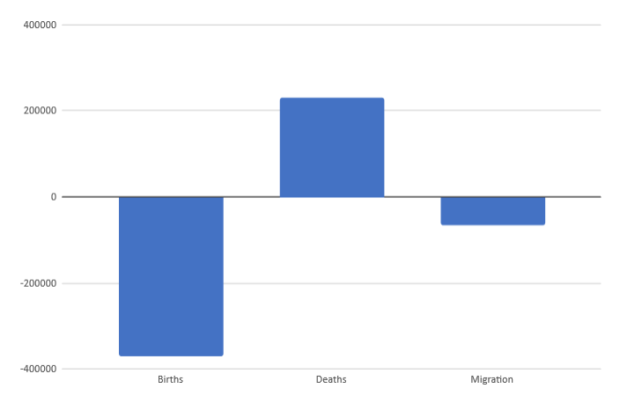

FIG 2: Difference Between Projected and Estimated Population Change by Component

In 2017 and 2018, the Census’ projection overestimated births by 317,000 babies, underestimated deaths by 230,000 deaths, and overestimated net migration by 67,000. In other words, for every component of population change, the Census projections were too optimistic.

What happens if we correct for these errors? If we use the same long-run assumptions about how death rates, fertility rates, and migration rates change over the long term as the Census Bureau uses, but we just use corrected recent-year data, how would our population forecast change?

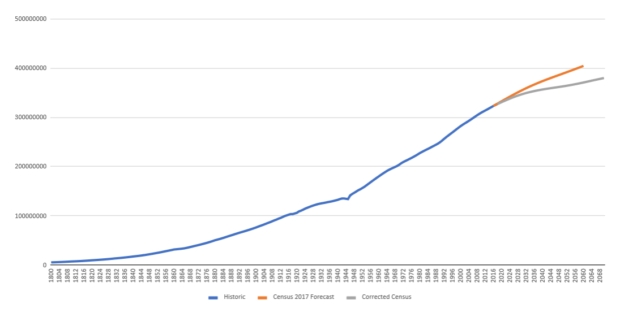

FIG 3: Corrected Census

That’s 34 million fewer Americans in 2060. And if we then allow ourselves to believe that the Census Bureau may have not only erred in recent years, but that the long run trend may be wrong as well, then it’s easy to arrive at a population scenario where U.S. population actually declines in the long run.

In a recent public forum on this topic, Dr. Phillip Cohen of the University of Maryland and I disagreed about the importance of long-run population decline: I said it was a big problem, he suggested it wasn’t so big a problem. And yet, his most optimistic scenario was tens of millions of people lower than the Census’ baseline scenario. That is, when it comes to serious public discussion by experts in the field, nobody believes the numbers Census is publishing.

Those numbers inform the fiscal projections done by CBO, OMB, OASDI, private firms, municipal and state governments, and other forecasting bodies. Even when Census’ numbers are not used verbatim, their projections serve as a benchmark. And when investors, public or private, don’t do their own due diligence to see if Census expectations are reasonable, massive malinvestment can result.

The careful reader may wonder why the Census Bureau’s projection is so wrong: are they aware of the problem? (RELATED: Tucker: Demographics In America Are Changing ‘Bewilderingly Fast’ — ‘Without Any Real Public Debate On The Subject’)

They are. I and others have notified them of the issue, and they are aware of it. However, there is a deeply conservative norm among expert demographers: long-run projections should generally be tied to extremely reliable data. Thus, some demographers have resisted efforts to produce any formal projection at all, even for crisis-stricken regions like Puerto Rico, because of a lack of sufficiently high-quality data. It is common in demography to see academic papers discussing “recent” trends whose last year of data was 5 or 10 years ago. In the Census Bureau’s case, they only use finalized data for long-run projections. Thus, the 2017 population projections, published in 2018, were benchmarked to birth rates from 1990 to 2014. They used some provisional data for 2015 as well. Their most recent input data was three years out of date.

But it must be said: Data reflecting 2018 birth rates was available in 2018. The Centers for Disease Control publishes monthly birth counts with between a 3 and 6 month delay. Census’ projections could have been more accurate.

This isn’t Monday-morning quarterbacking: I pay my bills by producing forecasts of birth rates for a variety of clients. The data is out there for the Census Bureau to produce a better forecast; I and many other private forecasters do so. But staid norms of academic and governmental forecasting, as well as, it must be said, a woefully insufficient human resources budget at the Census Bureau, result in clearly unreliable projections that mislead the public, and coddle policymakers into a false sense of security.

The near-certain reality is that future population growth will be far lower than the Census Bureau expects. It’s possible that American population could be declining by the middle of the 21st century. (RELATED: The United States Had Fewer Babies This Year Than In The Past 30 Years: Report)

America’s public and private institutions are not prepared for so sharp a demographic change. Nobody expected that fertility would fall so abruptly even as mortality would rise so sharply, and at a time when immigration rates are relatively low as well. Demographic tremors are already playing out: many retirees are finding that there just aren’t people around to buy the homes they planned to use as savings vehicles for retirement. Eventually, these tremors will turn into an earthquake as more and more municipalities, counties, and even states face irreversible demographic decline, leading to inability to pay for long-term liabilities, and in many cases even current services. By the time the problem becomes large enough to seriously impact the Federal budget, sometime in the 2030s or 2040s, it will be too late to turn things around.

Policymakers need to plan for the future today. Congress should, by statute, mandate that forecasting bodies like CBO, OMB, the Social Security trustees, and the Census Bureau benchmark their forecasts to most-recently-available data, and should demand periodic retrospective appraisals of forecast accuracy, as well as an accounting for sources of error. Congress could also consider ordering these forecasting bodies to procure independent, outside review and analysis of projections which will be used for budgetary purposes, although this could come with some costs attached (full disclosure: I privately provide services which would be similar to those contracted, and so would benefit from such a mandate).

Beyond these modest changes and new demands to forecasting bodies, Congress could also consider more sweeping changes. They could allocate more money for hiring of personnel in forecasting offices, on the understanding that spending a few hundred thousand dollars to get better forecasts is worth avoiding hundreds of billions of dollars of unplanned fiscal errors in the future. (RELATED: Study: US Birth Rate Is At 30-Year Low)

Congress could also change its own rules: the budget scoring window could be extended to require full present value budgeting. That is, rather than using gimmicks to push costs out beyond the 10-year budgetary window, Congress could bind itself, and require policymakers to confront the full cost of a policy across its whole lifespan, adjusted for future inflation and the time value of money. This would force policymakers to confront long-run budget realities today. Demographic changes move at a glacial pace: but, like glaciers, they move with incredible force, reshaping the land around them, and are extremely difficult to stop. Confronting demographic changes requires that policymakers incorporate 20, 30, 40, or 50-year effects into their planning.

But a good first step if Congress can’t commit to budgeting for the full cost of policy changes would simply be to expect more of its advisory bodies. Congress can and should demand of CBO, OMB, the Census Bureau, and the Social Security trustees that they benchmark their projections to more recent data, and go to greater effort justifying and explaining their forecasting assumptions. If Congress won’t demand that basic responsibility from its advisory bodies, then voters would be justified in holding their elected representatives fully responsible when cuts to Social Security are more severe, taxes are raised higher, and economic growth is slower than they were ever told to expect.

Lyman Stone is a Research Fellow at the Institute for Family Studies.

The views and opinions expressed in this commentary are those of the author and do not reflect the official position of the Daily Caller.

All content created by the Daily Caller News Foundation, an independent and nonpartisan newswire service, is available without charge to any legitimate news publisher that can provide a large audience. All republished articles must include our logo, our reporter’s byline and their DCNF affiliation. For any questions about our guidelines or partnering with us, please contact licensing@dailycallernewsfoundation.org.