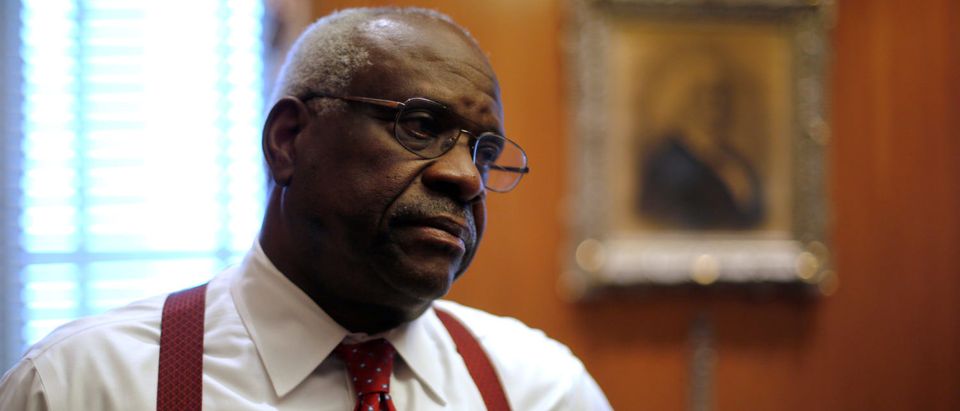

Conservative Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas insinuated social media platforms may have no right to censor speech in a concurring opinion Monday.

The case at hand was Biden v. Knight First Amendment Institute, filed in 2017 by a group of individuals who were blocked by former President Donald Trump’s personal Twitter account, @realDonaldTrump. The group alleged the account was a public forum and that their First Amendment rights were violated when Trump blocked them.

The high court dismissed a challenge as moot, with Thomas authoring a 12-page concurrence that said the larger question of whether digital platforms have the right to block users was not presented but needs to be addressed.

Thomas noted respondents had a point that “some aspects of Mr. Trump’s account resemble a constitutionally protected public forum” but it was “odd to say that something is a government forum when a private company has unrestricted authority to do away with it.”

The court rejected a separate petition alleging the digital platform “violated public accommodation laws, the First Amendment, and antitrust laws,” Thomas wrote.

“The petitions provide avenues for historically unprecedented amounts of speech, including speech by government actors. Also unprecedented, however, is the concentrated control of so much speech in the hands of a few private parties. We will soon have no choice but to address how our legal doctrines apply to highly concentrated, privately owned information infrastructure such as digital platforms.”

“If part of the problem is private, concentrated control over online content and platforms available to the public, then part of the solution may be found in doctrines that limit the right of a private company to exclude,” Thomas wrote.

Thomas then insinuated that digital platforms—such as Twitter, Facebook and Google—are akin to “common carriers” which are subject to special regulations and “a general requirement to serve all comers.”

U.S. law defines common carriers as private or public entities that transport goods or people from one place to another. Telecommunication services and public utilities are also described as common carriers. Thomas argues that while the question is up for debate, government regulation could be justified when a carrier such as a digital platform possesses substantial market power.

“But whatever may be said of other industries, there is clear historical precedent for regulating transportation and communication networks in a similar manner as traditional common carriers,” he wrote. (RELATED: Should Big Tech Be Treated As State Actors? This CEO Thinks So)

“In many ways, digital platforms that hold themselves out to the public resemble traditional common carriers. Though digital instead of physical, they are at bottom communications networks, and they ‘carry’ information from one user to another. A traditional telephone company laid physical wires to create a network connecting people. Digital platforms lay information infrastructure that can be controlled in much the same way.”

“And unlike newspapers, digital platforms hold themselves out as organizations that focus on distributing the speech of the broader public,” Thomas added.

Associate Justice Clarence Thomas poses for the official group photo at the US Supreme Court in Washington, DC on November 30, 2018. ( MANDEL NGAN/AFP via Getty Images)

Thomas said digital platforms have “enormous control over speech,” using Google as an example. “When a user does not already know exactly where to find something on the Internet—and users rarely do—Google is the gatekeeper between that user and the speech of others 90% of the time. It can suppress content by deindexing or downlisting a search result or by steering users away from certain content by manually altering autocomplete results,” he wrote.

Thomas said even if digital platforms are not deemed common carriers, there is still an opportunity for Congress to treat “digital platforms like places of public accommodation.”

“If the aim is to ensure that speech is not smothered, then the more glaring concern must perforce be the dominant digital platforms themselves. As Twitter made clear, the right to cut off speech lies most powerfully in the hands of private digital platforms,” Thomas wrote.

Thomas also noted that immunity granted to digital platforms under Section 230 of the Communications Decency Act “eliminates the biggest deterrent—a private lawsuit—against caving to an unconstitutional government threat.”