Serving as President of the Sandy Hook Water Association was largely a symbolic job for Gerald Wingert for most of the 41 years he filled the role.

Wingert, now retired but still active in his small rural Pennsylvania community, would lead meetings and handle some administrative duties for the association, but the beauty of the group was the same as the water system they relied on for decades: it more or less ran itself.

That was the case, at least, until the Pennsylvania state government got involved.

After 17 years of back-and-forth with the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection (DEP), the Sandy Hook Water Association’s “public” water system went offline this year. Mounting costs due to DEP regulations and legal headaches led the members to vote to disband, with many forced to instead dig wells or build cisterns to have access to clean water.

The three-letter agency succeeded in snuffing out a lifetime of work for Wingert and the dozens of others who helped provide a small community with clean, natural drinking water for more than half a century.

The Sandy Hook Water Association was established in 1965 by residents in rural southern Pennsylvania, ten or so miles outside the small borough of Chambersburg. The inhabitants discovered a natural spring in the mountainous terrain perched above their community and took it upon themselves to construct a system of pipes and plumbing to carry the spring water down the mountain to their homes below.

The system was 100% natural — no electricity nor pumps, just elevation producing natural water pressure flowing down the mountain. “God put that water there, they have nothing to do with that, that’s not their water,” Wingert said while giving the Daily Caller a tour of the community, referring to the DEP.

Gerald Wingert stands in front of construction machinery in Chambersburg, PA. (Karen Battersby)

The Association grew to the point where a few dozen families were getting all their water from the spring. The system is still operable today, nearly sixty years later, albeit with some changes enforced by the DEP. The water from the spring itself is still drinkable straight from the ground.

Gerry, as he’s known to friends and family, became President of the Association in the late 1970s and held the position until recently turning it over to Jason Forrester. He still advises Forrester, who says he knew nothing about water before meeting Wingert except it runs downhill and he needs it to live, on certain matters.

Gerald Wingert and Jason Forrester pose with construction machinery in Chambersburg, PA. (Karen Battersby)

For Wingert, Sandy Hook was a generational undertaking. His parents moved to the area in 1947. In 1966, the year after the Association was formed, he left for the Army and served in Vietnam. He returned to his hometown community, where five generations of Wingerts would go on to use the Sandy Hook water system.

His mind still sharp, Wingert can walk anyone through Sandy Hook’s water filtration building and explain how every meter and switch inside works. He knows the pipeline layout which lies beneath the mountainous dirt by heart, leading us around the grounds of the spring aided by crutches due to injuries sustained by exposure to Agent Orange in Vietnam.

“I raised my daughters on that water, they grew up on it. After I got out of service we bought a house in the neighborhood, lived there 32 years,” Wingert recalls. “I’ve lived in the neighborhood since 1947. So, it’s just — this is all completely useless,” he says as he gestures toward the filtration systems.

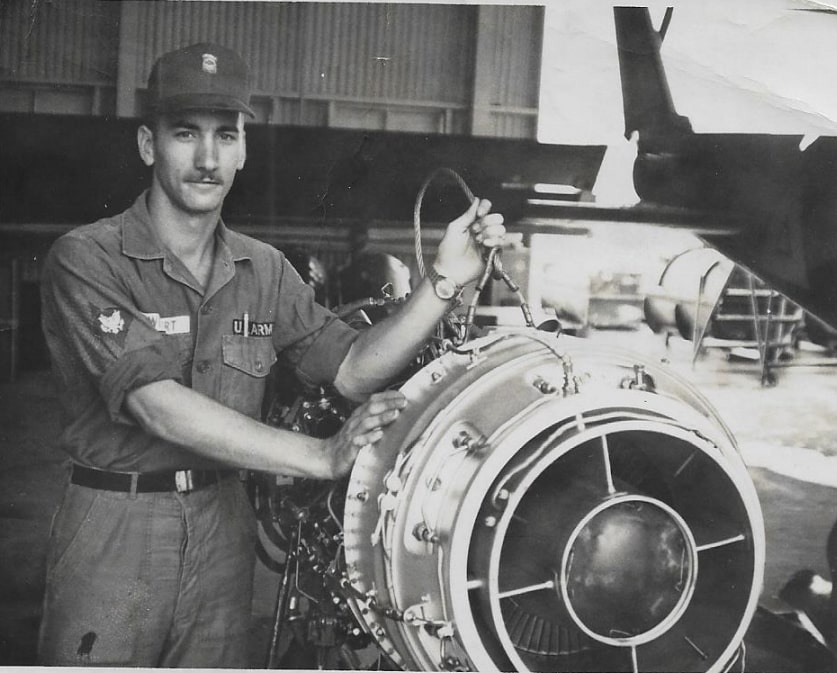

Gerry Wingert during his time serving in the Army during the Vietnam War. (Karen Battersby)

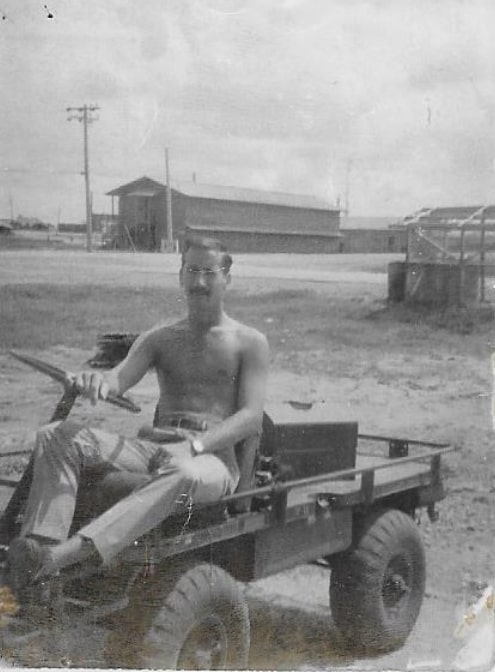

Gerry Wingert sits on a vehicle during his time serving in the Army during the Vietnam War. (Karen Battersby)

It wasn’t until 2006 that trouble began for the community. An anonymous tip was sent to the DEP alleging the unregulated spring water system could be a health hazard. To this day, the members of Sandy Hook don’t know for sure who sent in that tip — perhaps it was a genuinely concerned citizen, a vindictive neighbor who wasn’t allowed to join the water system or maybe someone else.

Regardless, that tip led the DEP to sink its claws in and never let go.

“When you’re dealing with DEP there, any way you do it, is their way. And you got to remember with DEP, common sense and what it costs are not in their equation,” Wingert said. “Anytime you take common sense out of an equation, you’re gonna have — you’re gonna have to add a multiplication table for what’s going to cost you. It’s just that simple. We’re talking simple crap here; we’re not talking anything high pitch.”

Back in 1965, the founding members of the Association kicked in $750 to get the system built and operational. For most of the years that followed, they paid somewhere around $25 a year for their water.

By the time the DEP was done with Sandy Hook and the system was decertified in 2023, the community had spent over $800,000 combined to comply with the onerous regulations imposed on them, all stemming from that 2006 tip.

The Sandy Hook Water Association filter building forced upon residents by the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection. (Daily Caller)

Those costs included installing new pipes, mechanized filtration systems, building a filter building and pumping chlorine into the water, among other things. While the reason for the initial tip remains unclear to this day, so does the motivation for the DEP’s intrusion into the lives of the Sandy Hook members. (RELATED: The “Clean Water Rule” Is About Federal Authority, Not Water)

It certainly isn’t a safety issue. The water ended up less clean after the changes than it was when pulled straight from the ground. The New York Times published data on contaminants in the water in a 2012 series on water pollution which showed it was exceptionally clean. 47 of the 54 contaminants tested for were not even traceable.

“Even though our water tests clean and off the charts, better than most municipalities, I think they said something about water is not 100%, the bacteria and things like that aren’t 100% dead unless it’s chlorinated,” Jason explains.

Daily Caller reporter Dylan Housman drinks water straight from the ground at the Sandy Hook water spring. (Daily Caller)

“We could have achieved that with the UV light at everybody’s house without any poison there. And I call it poison because it is poison, chlorine is poison,” Wingert chimes in to add. He said a technician once sent to the community to take water measurements told him he wished he could get readings this clean from his processing plants.

When the Sandy Hook members tried to find answers for themselves, DEP reportedly wasn’t cooperative. At a March 2020 meeting of the Association, several DEP employees showed up to discuss the situation with the members. When they attempted to start recording the exchange, a DEP official named Kristine Metzger told the members they would not speak with them if being recorded due to an agency policy. The members refused to stop recording. Metzger and the other DEP employees left.

Metzger could not be reached for comment on this story. In response to a public records request, the DEP claimed it did not possess any records of emails sent pertaining to that meeting in the months that preceded and followed it. The DEP refused to comply with several other public records requests filed by the Caller, claiming that they were too broad or unspecific. The DEP also did not respond to multiple requests for comment before the publication of this story.

The agency has dealt with a number of controversies during the years it was simultaneously cracking down on Sandy Hook. In 2020, the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania was sued by Maryland, Virginia, Delaware and Washington D.C. for disproportionately polluting the Chesapeake Bay. The jurisdictions settled earlier this year with an agreement Pennsylvania would be subject to increased federal oversight.

That same year, then-Attorney General Josh Shapiro found the DEP was not meeting its obligations to protect Pennsylvanians from the environmental consequences of fracking.

The DEP also has a history of suing local communities that try to stand up for themselves against corporate interests and bureaucratic overreach. In 2017, the agency sued Highland Township after the locality adopted a new provision to prevent corporations or governments from disposing of oil and gas waste in their community.

Communication over the years from the DEP to the community was cold and bureaucratic. Wingert and Forrester were forced to issue entirely unnecessary “boil notices” to comply with state regulations. Form letter after form letter was sent to them to inform them of various violations and changes needed to be made. Eventually those form letters turned into “consent orders” which coerced the Association into making various renovations under legal threat.

When the Association made the decision to shut down their system, all but a few taps were required by the DEP to be disconnected. Any system with 14 or more taps qualifies as a “public utility” in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, classification Wingert calls “bullshit.” To get the DEP out of their hair for good, the members of Sandy Hook had to disconnect enough taps to get under that limit.

Most of the households which disconnected were forced to dig wells to supply their water going forward since there isn’t a public water system available to them otherwise.

When faced with having to remove most members from the system, the Association voted to make the cuts in the fairest way they knew how: charter members who were still connected were given the first priority to stay on, followed by individuals who wouldn’t be able to dig wells or had financial constraints preventing them from investing in a new water source.

Many of the community members are retirees or otherwise on fixed income, leading to some hard decisions having to be made regarding cuts.

Records of water tests provided by the Association to the Caller indicate that at no point in time was the water used by the families of Sandy Hook unsafe to drink. Now some of the members have struggled to find even any water source.

“They started digging in June and dug for three or four days … The initial depth was 500 feet because that’s what we were hoping for, or quoted for,” one resident, Brandon Sherman, told the Daily Caller. “And then it kept going, I think a couple hundred-feet increments until eventually 800-feet, we were getting what we have now. I told them to keep going until 1200 and that was the cap.”

Sherman and his wife Crystal moved into the community in early 2022. They hadn’t been told the full extent of the water situation by the house flipper who was selling them their new home until it was too late to back out. With an elementary school-aged child to raise and another baby on the way, the family decided they’d make do in their new home with a well.

Brandon Sherman poses with his wife Crystal and their two children. (Brandon Sherman)

That well ended up costing the family $36,000, rather than the $25 per year which would have been paid under the original terms of the Association. Sherman, a maintenance technician for Ventura Foods, says he will be working Sundays for the next three to four years to pay off the loan he had to take out to get the well built.

Crystal, now parenting a six-year-old and ten-month-old, will keep working her job as a credit union analyst to help make ends meet.

“The person we bought the house from kept us in the know, at the most legal minimum that she was required to service,” Sherman, sporting a ZZ Top t-shirt after returning home from work one evening, said. “But it’s more frustrating the overreach of the three letter agencies in this country. That’s what’s more aggravating, honestly.”

Jason, whose day job is driving trucks for Martin’s Famous Potato Rolls, had a similar view of the situation. “It wasn’t your neighbors that did this to you, it was the government,” was the refrain which kept the community together as a majority of them were kicked off their water supply.

Over the years Sandy Hook was engaged in its fight with the DEP, they sought help in every corner. Members contacted government officials all the way from the most local level up to writing letters to the Trump White House. They explored legal options and hired attorneys to help guide them through the best process for dealing with DEP legal threats. They reached out to media companies to try to shed light on their situation, including the Daily Caller.

Resident Karen Battersby, who says she paid $24,000 for a well to be dug on her property, said she emailed the Caller out of a sense of desperation.

“We have turned to the chain of politicians elected by us at the local, state and federal level. Other than lip service and hearing how the state bureaucrats cannot be controlled we have not received any help,” she wrote. “We are begging to have our story told. We are begging to be heard.”

The officials they reached out to included U.S. Congressman John Joyce, Pennsylvania State Rep. Paul Schemel and Pennsylvania Sen. Doug Mastriano. Mastriano’s office was the most engaged on the issue, sending a representative to the March 2020 meeting which went awry and offering a show of support in the face of the DEP. Ultimately, however, the officials Sandy Hook asked for help were powerless against the “environmentalist tree-huggers” at DEP, as Mastriano staffer Doug Zubeck characterized them. (RELATED: EXCLUSIVE: Watchdog Group Sounds Alarm About Top EPA Official’s Ties To Prestigious Legal Center)

Now, months after that cry for help, Battersby says she knew it wouldn’t save their water, but the effort was worth it anyway: “We’re gonna lose, but we’re gonna fight.”

There was one common theme amongst everyone in the small community outside Chambersburg who spoke to the Daily Caller. When their government turned against them, their representatives ignored them and their lawyers failed to save them, their community is what stood behind them.

“We 1,000% feel like we were welcomed and everything was great for that,” Sherman said. “I don’t think we’d have that opportunity to know our neighbors as well had something like this not happened,” Crystal added.

When asked for his ultimate takeaway from the situation, Jason, who incurred expenses on the low end at about $9,000 to build a cistern, said it “confirmed everything I ever thought about alphabet agencies, but also everything I believed about the power of communities.”

But for Wingert, even the strongest sense of togetherness can’t fully replace the sense of loss which comes with seeing the Sandy Hook Water Association fade into memory. “To see what has happened to that system that our fathers put together for our community, it makes me want to cry, it’s beyond heartbreaking,” he said. “But it was a choice we had to make.”