- An atheist group filed a lawsuit in federal court challenging a war memorial cross in suburban Maryland, arguing it violates the Constitution’s ban on establishing religion.

- The Supreme Court said the memorial could remain on a 7-2 vote in June.

- These are the stories of three men named on the monument.

Just two days before Christmas, roughly 100 years ago, a family in Bladensburg, Maryland, received word from Washington informing them that their only son, John Henry Seaburn Jr., was killed in action on the fields in France.

Seaburn would later become one of 49 names of local boys etched into a pedestal holding up a gigantic 40-foot Celtic cross, which sits still today at the center of a roundabout in Bladensburg, Maryland.

That First World War veterans memorial — known as the Peace Cross — was the subject of landmark litigation concerning religion in public life. The Supreme Court turned back a challenge to the monument in June, ruling 7-2 that it did not violate the Constitution.

Three local residents brought a lawsuit against the state parks commission that administers the memorial in 2014. They won a favorable judgment in the 4th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals.

That litigation notwithstanding, Bladensburg’s hallowed roll is a rich history of the period.

Among those 49 we highlight here only three: an infamous expatriate, whose lost honor was restored on distant atolls; a black infantryman whose country did not permit him to muster under its flag; and a son of the American Revolution.

Henry Hulbert

The life and times of Henry Hulbert track the heady days of U.S. expansionism at the turn of the 19th century. A son of the English mercantile class, he was born 1867 in Kingston-Upon-Hull, Yorkshire, reared at a grammar school for aspiring sons of the bourgeoisie and married into a well-placed colonial family at 21.

His promising prospects dimmed thereafter — his appointment to the civil service in the British Far East terminated when he confessed to an affair with his sister-in-law. Disgraced and notorious, Hulbert pushed off for North America around 1897 to take up prospecting in the remote stretches of the Yukon.

The U.S. was on a war footing when Hulbert reached California in 1898. Seeing war with Spain was likely, he enlisted in the Marine Corps. Stationed aboard the USS Philadelphia, he was dispatched to the south Pacific in 1899 where he saw action during the Samoan crisis, a dispute between the U.S., the U.K., and Germany as to control of the Samoan Islands.

A vastly outnumbered Marine expeditionary force in which Hulbert was embedded engaged German-backed Samoan fighters at the Second Battle of Vailele in April 1899. Though the Marines and their native allies were soundly defeated during that engagement, Hulbert’s commanding officers commended his gallant defense of the American retreat, writing that his performance against overwhelming odds was “worthy of all praise.” He received the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1901.

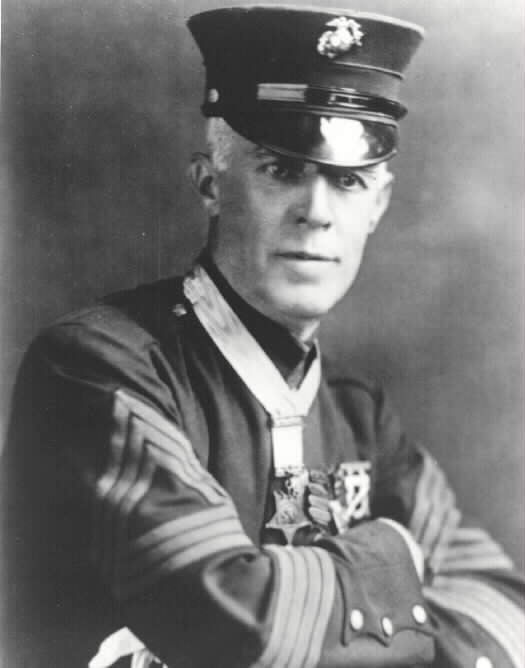

Henry Hulbert, wearing the Medal of Honor, is seen in this undated photo. (Credit: U.S. Marine Corp)

Hulbert periodically saw combat during subsequent postings to Panama, Guam, and the Philippines. After several terms of service abroad, he was detailed to the staff of Marine Commandant George Barnett in Washington, D.C. During this period he lived in Riverdale, Maryland, with his second wife Victoria Akelitys, establishing his connection to Prince George’s County.

Admired at Marine Headquarters and deeply knowledgeable about many dimensions of military life, some sources indicate that a specially composed examining board designated Hulbert as the Corp’s first Marine Gunner in March 1917. (RELATED: Media Alarmed After Justice Thomas Calls For Review Of Landmark Free Press Ruling)

When the U.S. entered World War I, the 50-year-old Hulbert agitated for an appointment in France despite his advanced age. Taking command of a platoon in the 5th Marine Regiment, he participated in the brutal fighting at Belleau Wood and Soissons during the summer of 1918. Promotions and official citations for acts of bravery followed.

Such was Hulbert’s reputation for ferocity and excellence that Gen. John Pershing, commander of U.S. forces in Europe, personally recommended him for commission as a captain.

The English exile died in the service of his adopted country at Blanc Mont Ridge near Reims on Oct. 4, 1918. His remains were interred at Arlington National Cemetery in September 1921.

Four months before Hulbert’s death in France, a Clemson-class naval destroyer left the Norfolk Navy Yard bearing his name. The USS Hulbert was moored at Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941. Naval History and Heritage Command believes the Hulbert was the first American ship to return fire on the Japanese attackers and is credited with the destruction of one torpedo bomber. The ship received two battle stars for service during the American island-hopping campaign in the south Pacific before its decommissioning in 1945.

John Henry Seaburn Jr.

It was no small gesture to list the black and white war dead together on a Maryland veterans memorial in 1925. Just one month after the Peace Cross’s dedication, 30,000 Klansmen — “22 abreast and 14 rows deep” by The Washington Post’s telling — staged one of the largest displays of hate in the nation’s history just seven miles south of the monument, demonstrating over several days on the National Mall.

Though segregated in the service, organizers named the Prince George’s county fallen together on the memorial.

One of the area’s black volunteers was John Henry Seaburn Jr., born in Washington, D.C., on Oct. 27, 1897. Data from the 1910 census shows that the family relocated to Brentwood, Maryland, in Prince George’s County. His father claimed employment as a fireman and both parents indicated they were illiterate. An ancestral connection to slavery is possible, as Seaburn Sr. was born in the border state of Maryland, while his wife Annie was from Virginia, a slave state.

A 1921 report in the Washington Evening Star shows that Seaburn served in the Washington, D.C., National Guard as a private stationed on the Mexican border. Publication of the so-called Zimmerman telegram in January 1917 inflamed American opinion against Mexico — the secret communique from Berlin to Mexico City promised economic aid and the recovery of lost territory in the American southwest if Mexico joined the central powers.

Subsequent to his border tour, Seaburn deployed to France in March 1918 in the 372nd Infantry Regiment, disembarking at St. Nazaire. His unit was a segregated African-American regiment placed under French command, attached to the so-called “Red Hand” division. The entire regiment received the Croix de Guerre, a French military decoration, for services rendered during the Meuse-Argonne advance, the last Allied offensive of the war.

John Henry Seaburn is seen in this undated photo. (Credit: Courtesy of First Liberty Institute)

Seaburn was killed in action Oct. 4, 1918 — the same day as Capt. Hulbert — near Monthois. A contemporaneous account of the 372nd’s movements from a black chaplain named Arrington Helm indicates that the German army met the regiment’s advance with determined opposition and heavy fire. His family was notified of his burial two days before Christmas.

The division commander, Gen. Mariano Goybet, issued a letter four days after Seaburn’s death commending the regiment’s performance in the combat of the previous week.

“Allow me, my dear friends of all ranks, Americans and French, to thank you from the bottom of my heart as a chief and a soldier for the expression of gratitude for the glory which you have lent our good 157th Division,” the letter reads. “I had full confidence in you but you have surpassed my hopes.”

Initially buried in a battlefield plot, Seaburn’s remains were transferred to the U.S. after the war. He was laid to rest with military honors in a segregated section of Arlington National Cemetery in July 1921. An American Legion post in Bladensburg was named in his memory.

The Seaburn family commemorated his sacrifice with a poem in the Washington Evening Star on the sixth anniversary of his death.

“Your memory is as sweet today as in the hour you passed away,” the poem reads. (RELATED: Judges Can’t Rule From The Dead, Supreme Court Rules)

Thomas Fenwick

Pfc. Thomas Fenwick was the scion of an old Maryland family. Among his ancestors were Col. Ignatius Fenwick, a Revolutionary War patriot, and Bishop Edward Fenwick, O.P., colloquially styled “the apostle of Ohio,” who founded the first Dominican chapter house in North America.

Fenwick, a much-watched pitcher for the local baseball team, enlisted as an infantryman in the Maryland National Guard, which devolved to the 115th Infantry, in the spring of 1917. Like his family, his infantry unit had old Maryland patrimony.

Some regiment historians argue that the 115th was first composed in 1775 when Capt. Michael Cresap raised a company of riflemen on the Maryland frontier after the skirmishes at Lexington and Concord. The 115th’s motto — “rally ’round the flag” — derives from the Civil War Battle of Front Royal, where Maryland infantry heroically stood their ground despite certain annihilation.

At 22, Fenwick deployed for France aboard the USS Covington as a machine gunner. His tour of duty was short-lived. Fenwick’s niece, Mary Ann Fenwick LaQuay, told the Daily Caller News Foundation that Fenwick died one week after exposure to a deadly chemical agent on Oct. 7, 1918. As with the Seaburn family, the Fenwicks were informed of Thomas’s death at Christmas.

“He was in a trench when the Germans used gas,” LaQuay told the DCNF. “But he didn’t die right then and there. Because of the gassing, he got pneumonia, and he died of pneumonia.”

LaQuay’s home sits on the same street as the house Fenwick left when he enlisted. She says the Peace Cross is a proxy gravestone for her family.

“I feel like my uncle is buried there, even though he is in Arlington,” she told the DCNF. “Every time I go by it, I remember him. That’s why that cross was put there — so that we don’t forget those 49 men.”

EDITOR’S NOTE: This article was originally published Feb. 26, 2019, and has been updated with new information.

All content created by the Daily Caller News Foundation, an independent and nonpartisan newswire service, is available without charge to any legitimate news publisher that can provide a large audience. All republished articles must include our logo, our reporter’s byline and their DCNF affiliation. For any questions about our guidelines or partnering with us, please contact licensing@dailycallernewsfoundation.org.