During just 42 hours this past November, Elizabeth Warren held town halls in five Iowa cities. Indeed, she held 96 Iowa events in 2019 — that’s eight a month for a senator whose home state is 1,300 miles away from Des Moines, a major-league logistical lift. Senator Bernie Sanders, South Bend Mayor Pete Buttigieg, Senator Amy Klobacher and former Vice-President Joe Biden have comparable Iowa event numbers.

In total, that’s more than 500 appearances in just one state for just five candidates; a conservative estimate of forums in the four February contest states for all 12 candidates would easily quadruple that number.

Thousands of events, each one carefully planned and choreographed, all aimed at driving polls, fundraising, and media coverage. And behind every single venue and candidate are the invisible players in the presidential primary panorama: the campaign advance team. (RELATED: Latest 2020 Democratic Primary Poll Sees Mike Bloomberg Surge Past Elizabeth Warren Into Third Place)

CEDAR RAPIDS, IOWA – JANUARY 26: Democratic presidential candidate, Sen. Elizabeth Warren (D-MA) speaks to guests during a campaign rally at The NewBo City Market on January 26, 2020 in Cedar Rapids, Iowa. The 2020 Iowa Democratic caucuses will take place on February 3, making it the first nominating contest for the Democratic Party in choosing their presidential candidate to face Donald Trump in the 2020 general election. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

As a one-time advance man, I know firsthand that a personal meet-and-greet in a 20-seat diner or a roof-raising speech to 4,000 in a college fieldhouse takes enormous skill and execution.

What it Takes

Prepared weeks and sometimes months in advance, a campaign schedule is masterwork of opposites – minute detail and wide-ranging strategy. Consider just one day in a six-month plan: The candidate attends a voter-registration rally in six-zip code Davenport, Iowa and before the last supporters have even left their seats, the candidate motorcade is on to a Dubuque community center and then a VFW hall in Muscatine.

In the advance man’s fondest dreams, every stop will feature hundreds of hysterical followers and microphones that work, fawning media coverage and a laudatory shout from the finance team because of unprecedented on-line donations. That one priceless appearance will push the candidate firmly over the top in 21 zip codes and demonstrate to all that the campaign is unstoppable on the road to victory.

The Art of Advance

But back to reality, the art of advance is slightly less glamorous. That Davenport rally really began a few days before. The advance team came together from the four points of the compass to traverse the city looking at possible venues, indoor or outdoor. (Yes, even in Iowa or New Hampshire in January: recall then-Senator Obama’s Presidential campaign announcement on February 11, 2007 in Springfield, Illinois – temperature 15 degrees, 9 with wind chill.) The site considerations are legion: Is the hall too big to fill, or too small, telegraphing to the press that the candidate can’t draw a crowd? (RELATED: 2020 Democratic Hopefuls Blame Iowa’s Floods, Tornadoes On Climate Change. What Do Scientists Say?)

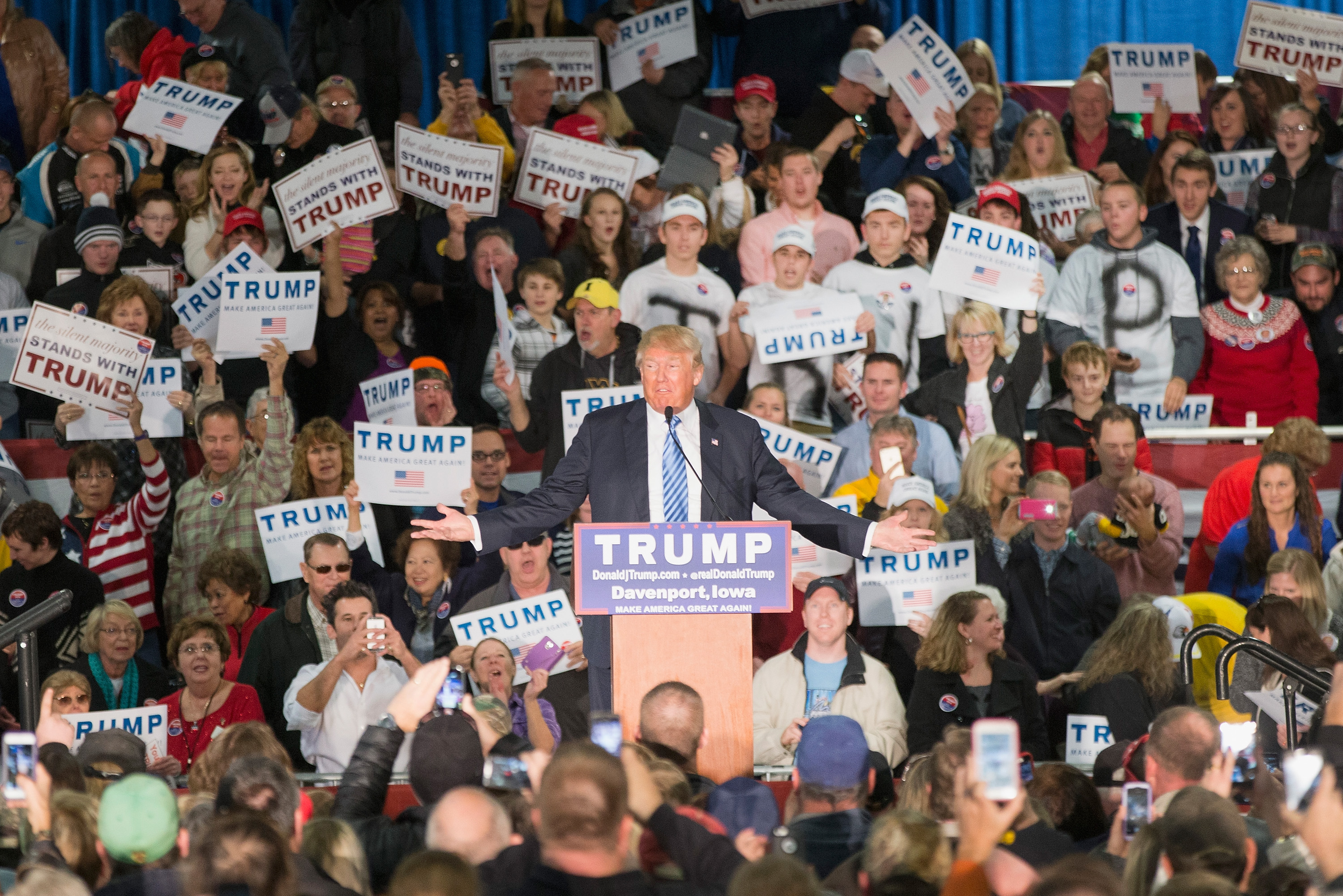

DAVENPORT, IA – DECEMBER 05: Republican presidential candidate Donald Trump speaks to guests gathered for a campaign event at Mississippi Valley Fairgrounds on December 5, 2015 in Davenport, Iowa. Trump continues to lead the most polls in the race for the Republican nomination for president. (Photo by Scott Olson/Getty Images)

After a site is chosen, local vendors are hired to build a stage with shadowless lighting and impeccable sound equipment; press risers are erected at just the right angle and height to catch the candidate against a striking backdrop of bleachers full of crazed and diverse supporters. Local fire-breathing backers are dispatched on a crusade to find enough bodies to pack a tiny community center or a minor-league baseball stadium. Staffers are sent to the local FedEx store to design and print up tickets, brochures, and placards for the rally; another guy drives and drives to find the ideal route from the airport at which the candidate arrives; rental vans are secured for campaign staff and press following the candidate. Others are calling, emailing, and pleading for the attendance of every reporter within 50 miles.

Game Day, and Plan C

Then, as advance guys put, it’s Game Day. The team has been up all night, anxious and rehearsing again and again. Everything at the venue is set, and it seems like nothing can go wrong. Except that anything can happen. The sound system suddenly has nonstop feedback, the principal stumbles and falls on an uneven portion of the stage, there are empty seats, the motorcade hits heavy traffic, the press van gets lost, a crowd warm-up dignitary won’t shut up, and hecklers emerge from a rival campaign. A single moment can doom an event.

Which is why advance guys always have a Plan C, even if it isn’t planned.

Once in Marietta, Ohio, I was on an advance team and 90 minutes before the campaign plane landed we were told the candidate insisted on having potted poinsettia plants ring the edge of the stage.

Check. I race to a nearby Walmart and buy every poinsettia the store has and while loading them on a flatbed hand truck, pass a display of roses priced to move at half off. Advance man intuition, not genius, kicks in: I buy every bunch. As I’m hustling the poinsettias onto the stage, we get a call from the campaign manager – we gotta have gifts for the cheerleading team traveling on the plane. Yeah, you guessed it – a bouquet of roses for every young woman.

When Advance Goes Right

There are legends in this game who’ve pulled off incredible successes: Mort Engelberg arranged the July 1992 six-day bus tour candidate Bill Clinton and running mate Al Gore took following the Democratic Convention in New York, extending the momentum and helping the ticket surge 20 percentage points in a month.

Obama campaign official Alyssa Mastromonaco orchestrated the then record-setting October 18, 2008 rally below the St. Louis Arch, attracting an astounding 100,000 supporters (that same day I was helping set up a rally in Philadelphia for a dispirited 250). Mastromonaco broke her record a week later in Denver with an event attracting an estimated 140,000 attendees.

US Democratic presidential candidate Illinois Senator Barack Obama greets supporters during a rally under the Gateway Arch in St Louis, Missouri, October 18, 2008. AFP PHOTO/Emmanuel Dunand (Photo credit should read EMMANUEL DUNAND/AFP via Getty Images)

For sheer political frenzy and an event that would presage the future campaign stops, George Gigicos, chief of advance for then candidate Donald Trump, oversaw an August 21, 2015 rally for more than 30,000 in Ladd-Peebles Stadium in Mobile, Alabama, the largest crowd in the 2016 GOP primary.

And When It Goes Wrong

The most iconic and unfortunate advance team failure (Sterling Heights, MI, September 18, 1988) resulted in the photo of a helmet-wearing Michael Dukakis in the turret of the M1- Abrams tank. Even 25 years later, the Politico story says it all: Dukakis and the Tank: The Making of a Political Disaster.

Lesser known but just as painful was Bob Dole, on September 18, 1996, in Chico, CA, leaning on an unsecured railing and falling off a stage, reinforcing the age trope in a contest against a genuinely vibrant ticket. (RELATED: ESPN’s College GameDay Will Be At The Iowa State/Iowa Game In Ames)

Both the success and failure scenarios consume an advance man, with the February contests placing the teams of all 12 candidates at full throttle. From Ames to Aiken, the scramble is on, with every event a chance for a candidate to catch lightning in a bottle, prove their campaign is on fire, and move on to March. Every day for the next month is Game Day.

Jeff Nelligan worked for three Members of Congress, was twice a Presidential appointee, and has served as an advance man on municipal, Congressional, Presidential, and national advocacy campaigns. He is the author of Four Lessons From My Three Sons: How You Can Raise Resilient Kids and writes at ResilientSons.