Donald Trump came in third in Minnesota’s Republican caucus, didn’t do well at North Dakota’s convention this Saturday, and is expected to lose handily in Wisconsin tomorrow night. The question is…why?

Here’s one theory: These are all places with high “social capital”—relationships and networks that connect us and enrich our lives. The phenomenon as made famous in Robert Putnam’s classic 2000 book “Bowling Alone.”

Essentially, much of America is suffering from anomie and atomization. People don’t know their neighbors or feel like they’re part of a community. Trump tends to do well in these areas.

But some places like Minnesota, North Dakota, and Wisconsin still do maintain high social capital. These are places where people still join bowling leagues. And, perhaps not coincidentally, these are places where Donald Trump seems to perform the worst.

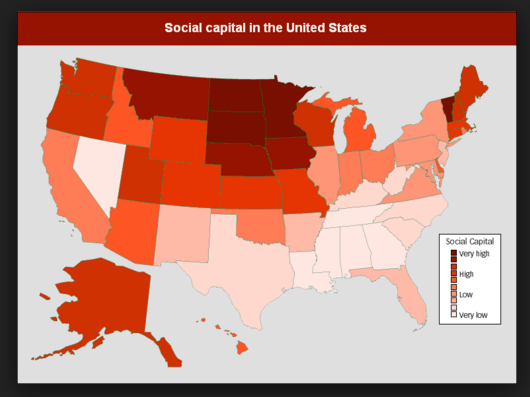

Here’s a map Putnam uses. It is important to note that some of these states haven’t voted yet. But it is interesting to note that Trump tends to do very well in the states with low social capital (Texas, home of Ted Cruz, being an obvious exception). And (with the exception of New Hampshire), Trump tends to perform less well in places with high social capital.

There may be reasons why, as the New York Times observes, Trump’s coalition “fades as one heads west.” Again, his support tends to be stronger where social capital is the weakest.

In fact, looking at a map of states where Trump has won is almost a mirror image of the map above (again, the caveat being that some of these states haven’t voted, yet).

I’m not the only one who has noticed. As Michael Barone wrote recently, “Looking over the election returns, I sense that Trump’s support comes disproportionately from those with low social connectedness.” Barone also notes correctly that Evangelicals who attend church regularly are less likely to support Trump. Conventional wisdom has been that these are more committed and devout Christians, but it could also have something to do with their being connected to a community. As Barone also notes, this might explain why the tight-knit Mormon community in Utah rejected him so soundly.

In terms of social capital, it might make sense for people who no longer feel they are connected to a larger community to want to “Make America Great Again.” These people might be more vulnerable and fearful than other Americans. These people might feel like their lives are more chaotic and disconnected, even if there is little empirical evidence to support it.

Trump, the cult of personality, has also started his own movement. There’s a sense of community right now for those who support him. Might it not be likely that people lacking community would be more susceptible to getting swept up in this sort of moment? As Clare Malone wrote at FiveThirtyEight, “Along with the fighting, though, something inspirational seems to be happening among the assembled — a sense of collective identity being discovered.”

Whatever the case may be, it is worth noting that Trump’s appeal does clearly tend to be, somewhat, geographical. In a world where we now all consume the same national media, it is refreshing to see that America has preserved some cultural diversity and unique characteristics.

I’m curious to see if this pattern continues when states like South Dakota and Nebraska (home of Trump foe Ben Sasse) get their chance to weigh in on The Donald.