By Mike Cumpston, GUNS Magazine

Fascination with historic firearms and modern reproductions is an enduring component of the Gun Culture. Many of the reproductions are available in kit form but even the ones factory finished are festooned with proof marks, modern address lines and cautionary literature. They look just fine from across the room but enthusiasts, re-enactors and cinematographers usually like to shorten the viewing distance considerably.

Some time in the late ’70’s or early ’80’s, I finished one of the early Lyman Great Plains Rifle in kit form. The eventual results closely resemble an original rifle from the early to mid-19th Century. Stock and metal finishing kits and related chemistry from Birchwood Casey and concise instructions enabled the project at minimal cost. My vestigial skill set in such matters was completely equal to the task.

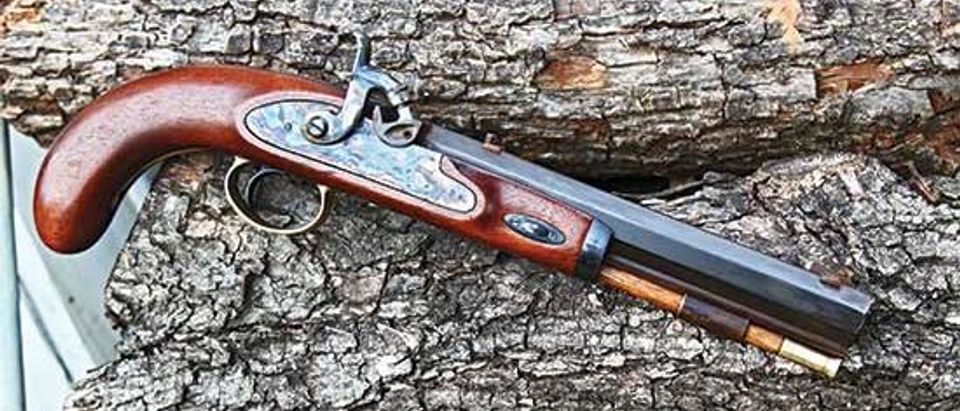

In 2003, I bought a ready-made Lyman Plains Pistol in .50 caliber to complement the rifle. Like the rifle, it comes from a partnership with Investarms of Italy and is made of quality walnut and steel. The lock contains the same components as those from the 19th Century though the leaf spring has given way to a very durable coil spring. A smaller version of the rifle lock, it even has the “fly” necessary for a set trigger. While the pistol is not equipped with a hair trigger, the very careful shooter can achieve the same effect manually. The Plains Pistol resembles a less ornate version of the Manton target pistols made in the period 1820 to mid century.

Rifled barrels on pistols became more common during this period and appear on target and general purpose handguns. Loading, handling and the excellent accuracy is comparable to the current Moore, LePage and other reproductions from the Pedersoli Company—making it easier to shoot accurately than many modern target-grade pistols. The patent breech makes it easy to clean compared to the general run of black powder arms.

Lyman recommends a maximum charge of 40 grains of unspecified black powder or the equivalent volume of Pyrodex with a patched 0.490- or 0.495-inch ball of approximately 175 grains. Loaded with GOEX FFFg, this charge will register 884 fps. Swiss FFFg will deliver 1,040 fps and the Pyrodex P black powder substitute clocks 934 fps. All deliver similar accuracy at 25 yards and beyond.

Though unadorned with engraving or enhanced woodwork, the quality of the pistol—its component parts and overall construction—is quite gratifying, and the only anachronistic features are the address lines, warnings and proprietary literature occupying the top three flats of the barrel.

The muzzle-heaviness and good trigger make off-hand shooting easy.

–

Birchwood Casey is also known for their visible impact targets. At 25 yards, the Lyman, like the general run of high quality replicas of rifled 19th Century target pistols, are very easy to shoot.

Woodwork

The Lyman Stock is crafted from walnut and fully compatible with the water-based walnut stain and True Oil finish supplied in the Birchwood Casey kit. Incidentally, the end results are far better than is obtainable with the birch stocks supplied with many lesser kits. Lyman’s instructions verify adding additional coats of True Oil can improve the factory applied “oil” finish. Internet “experts” and even professional stockmakers who actually know what they are about, often argue True Oil is actually light varnish.

Nonetheless, it is demonstrably compatible with the Lyman finish and many modern handgun grips also benefit from additional attention. The stock being finished with the grain well filled, the only preparatory step needed with my pistol was a light going over with the kit-supplied fine sandpaper and steel wool to clean and prepare the surface. I applied the walnut stain full strength and, per instructions, let it sit overnight. Very light coats of True Oil are applied barehanded a day apart with the first coats lightly steel wooled—particularly when working with unfinished wood. Succeeding coats, still very light, build up the finish that hardens at a very high sheen. The verisimilitude with early oil-finished gunstocks emerges after hand application of the pumice stone powder bottled by BC as Stock Sheen and Conditioner. Fully hardened, the finish is durable and a pretty effective barrier to normal environmental factors. The kit contains Gunstock Wax for additional protection.

While the wood-to-metal/metal-to-metal fit isn’t quite as seamless as found on early Manton or ePage pistols, it is close enough to keep the powder residue from entering the lock or covered parts of the barrel.

–

The Lyman Lock proves to be as durable and problem-free as claimed. It is a near copy of the original design with substitution of a coil spring for durability.

–

The barrel and furniture are all fabricated from steel except for the brass triggerguard. Birchwood Casey also has chemicals to blacken or “antique” brass if so desired. A fairly large, sharp flat file is needed for drawfiling—a process detailed in the Lyman kit instructions—for removing tool marks from the raw barrels. Front and rear sights removed, it is a simple and straightforward operation and my additional goal was removal of the unwanted literature on the barrel flats. This aspect proceeded fairly quickly without doing any mischief to the overall symmetry of the octagonal barrel, even though the flats in contact with the stock are left unfiled. The patent breech can be temporarily Super-Glued to the barrel tang to preserve its lines.

The blue-remover in the Permablue Gun Bluing kit was quite effective as was the cleaner-degreaser. It is necessary to preserve the raw metal from oil-including fingerprints during the browning process. I wrapped fine sandpaper around flat wood to preserve the sharpness of the barrel flats and polished the barrel to a high shine short of a mirror finish. I put the barrel in an oven to bring it to the prescribed 275 degrees though heating with a propane flame to the point the browning solution sizzles on the metal is the suggested alternative.

The browning chemicals are a wonderful colloid of caustic elements including the components of many of our favorite explosives. They include nitric acid, sodium nitrate and potassium chlorate. Eye protection and gloves are recommended. It is applied with cotton swabs until the steel cools to the point it stops sizzling. Then allow to work until it reaches room temperature. The surface is then cleaned with steel wool, degreased and the process repeated until the desired even dark brown matte finish emerges. The process is stopped by rinsing and application of light gun oil. The resulting brown matte finish is durable and closely resembles the historic treatment accomplished by slow oxidation over a considerable time.

Wood and metal finishing kits contain the basic tools and elements including chemistry, sandpaper, steel wool and applicators. Other products include brass antiquing or blackening, Aluminum Black and Browning solution. The Super Blue version of their Perma-Blue is particularly useful for touch-up work on modern or antique arms.

Results

The finished, “defarbed” pistol now looks a lot closer to an original arm of the same type. One individual who saw the final result remarked I am a true artisan (much appreciated, but an observation nowhere close to accurate). The comprehensive array of chemistry, and application tools supplied by Birchwood Casey, time, adherence to the detailed instructions and no particular dependence upon the talent of the operator other than following instructions comprise the key elements of the successful defarb.

These kits are normally cash and carry (depending on how blue your state is), so they make pretty good Christmas gifts if your giftee has any proclivity to spending the time to put it together. Retail price runs around $350.

Thanks to GUNS Magazine for this post. Click here to visit GUNSMagazine.com.

Better yet: Click here to get GUNS delivered to your door.