Many independent journalists in Russia have fled the country over the last year due to new laws introducing harsh media censorship, but news outside of the veil of the Russian government, including coverage of the war in Ukraine, continues to get through to those who are willing to look for it.

Andrey Zakharov, an investigative reporter working for BBC’s Russian-language service, left Russia months before the war on Ukraine began after he was deemed a “foreign agent” in October. Now in Europe, he continues to publish investigative reporting and posts news regularly to a Telegram audience of nearly a quarter million people.

“It’s very hard to live in Russia” after being labeled a foreign agent “because you’re always nervous about it,” he told the Daily Caller in an interview. A Russian law was modified to allow journalists to be included on the list in late 2019.

Being a “foreign agent” means “putting a very awkward disclaimer” stating the “foreign agent” status on everything one publishes — including social media posts — and “sending a financial report to the Ministry of Justice” every few months, he said.

If one forgets, they can get fined. “If you get fined more than two or three times, you can be put into jail,” he continued.

Journalists feel like the modification of the “foreign agent” law was Russia “preparing for the war long before the war started,” he said, as it made many independent journalists leave Russia in 2021.

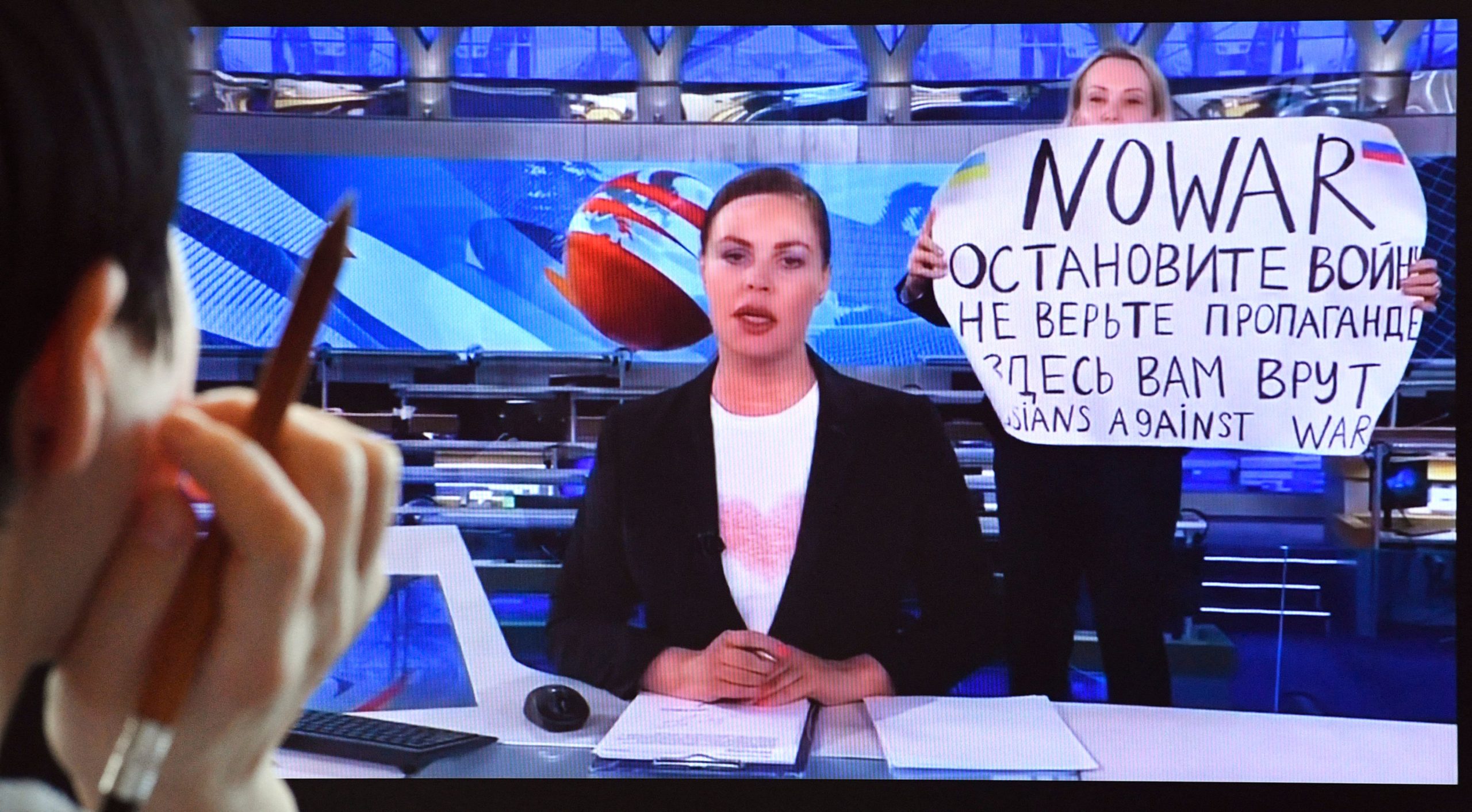

Since Russia launched its invasion of Ukraine Feb. 24, Russia has imposed bans on Facebook and Instagram, labeling them “extremist” after parent company Meta allowed for hate speech against Russian soldiers in some countries. Russia also passed a law March 4 that banned the publication of narratives contrary to those of the government. Several independent media companies in Russia shut down due to the law, with their employees fleeing abroad. Offenders of the new law can face up to 15 years in prison. (RELATED: ‘They’re Lying To You’: Woman Runs Into Frame, Interrupts Live Russian Broadcast)

Still, some local media publish “important content,” Zakharov said. “They can’t use the word ‘war'” and have to follow the rhetoric from the Kremlin, but they write stories about the “economic crisis” and inflation, he added. People can start to “understand that something is going wrong.”

However, even when Russians see these local stories and independent coverage on Telegram, it doesn’t necessarily mean they will believe it, he said, as some will dismiss it as “fake news.” A deeper financial crisis in Russia may be the catalyst to make more people believe in it, Zakharov said.

A woman looks at a computer screen watching a dissenting Russian Channel One employee entering Ostankino on-air TV studio during Russia’s most-watched evening news broadcast, holding up a poster which reads as “No War” and condemning Moscow’s military action in Ukraine in Moscow on March 15, 2022. – As a news anchor Yekaterina Andreyeva launched into an item about relations with Belarus, Marina Ovsyannikova, who wore a dark formal suit, burst into view, holding up a hand-written poster saying “No War” in English. (Photo by AFP) (Photo by -/AFP via Getty Images)

Mark Narusov, a recent Moscow undergraduate in his early 20s who has protested against the war in Ukraine both via demonstration and on social media, said that Russia’s media censorship is the worst it has been in recent history, but most young people are getting around bans on social media for now with a virtual private network (VPN).

Russia’s ban on Facebook and Instagram is “a less big of a deal than it looks like on paper” due to mass access to VPNs, he told the Daily Caller, but businesses are harmed since they are dissuaded from advertising.

However, anti-war content on social media has become increasingly rare after Russia’s March 4 media censorship law, according to Narusov.

“Since then it has become truly rare to see people posting against the war from open accounts, under their real names and while physically residing in Russia,” Narusov said. (RELATED: EXCLUSIVE: Borderline Sexual ‘Torture’: Protester Says He Experienced Firsthand What Happens Inside Russian Police Stations)

“You have to be very careful with what you post,” an active social media user in St. Petersburg told the Daily Caller.

The Daily Caller granted this social media user anonymity due to safety concerns.

“I’m afraid it might ruin my career. Also, you might be excluded from university if you have a record that you went to an anti-war protest and were detained,” she said, claiming that those who do not openly protest support independent media by donating.

Most Russians who want access to independent media use Telegram, where Russian media sources, including those that continue to work from abroad like Zakharov, post on a regular basis about the war, she said.

Telegram would be difficult to block because it’s used by all Russian officials, according to Zakharov, but Russia may move to block it and platforms like YouTube in the future. Only regime change will change the movement towards more censorship, he said.

“A lot of people in Russia don’t want this war, we don’t want this government, we didn’t choose them,” said Alexandra, a social media user with thousands of followers who was granted anonymity due to safety concerns. She cited similar fears of getting fined, jailed, fired or expelled from university for making the wrong comments online.

Another social media user, also granted anonymity from the Daily Caller for safety reasons, said she is afraid that she’s being watched by the Russian government after she was detained at a police station and interrogated at her house for her previous comments about the war.

“When you live in Russia, you never know what information will be used against you,” she said. There have been times when the government prosecuted people for commenting and liking anti-war posts on social media, she said.